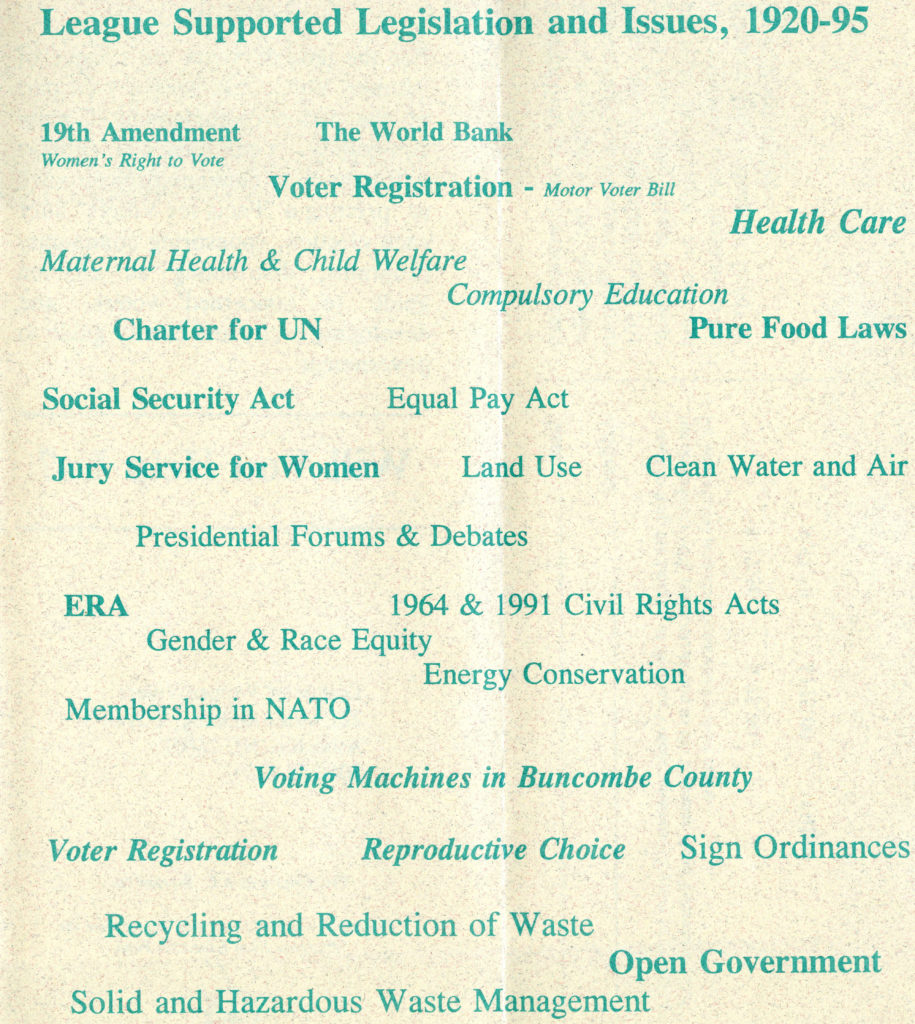

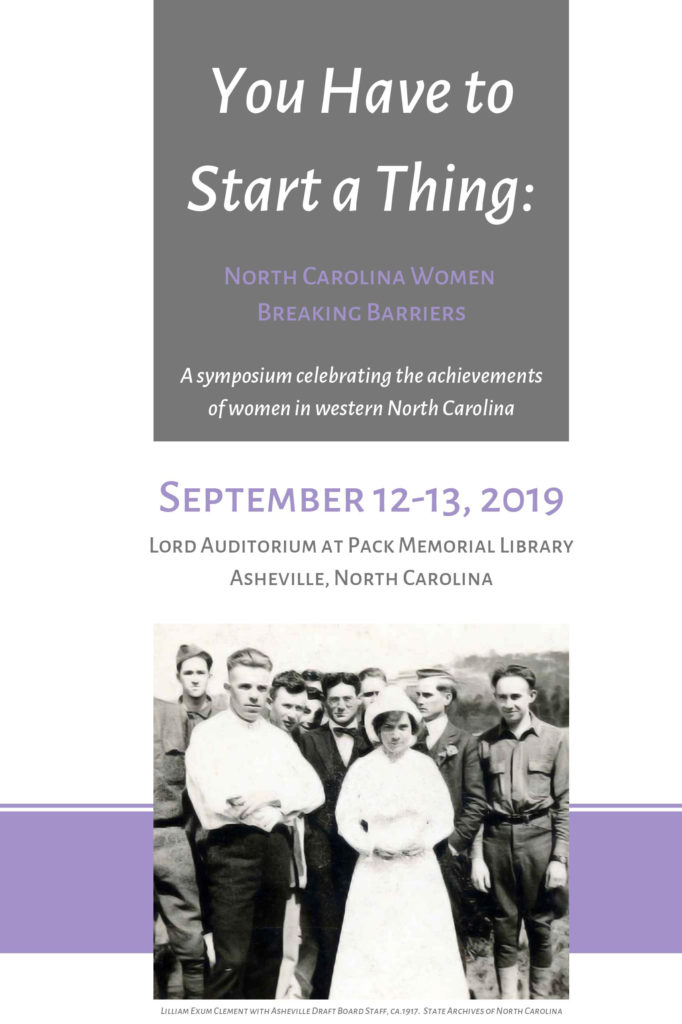

“We are living through one of those rare moments in history when profound changes are being made in our social and economic order… University women should be the leaders in reviewing old laws and testing them… We should be familiar with proposed laws and assist our community in understanding their full significance.”

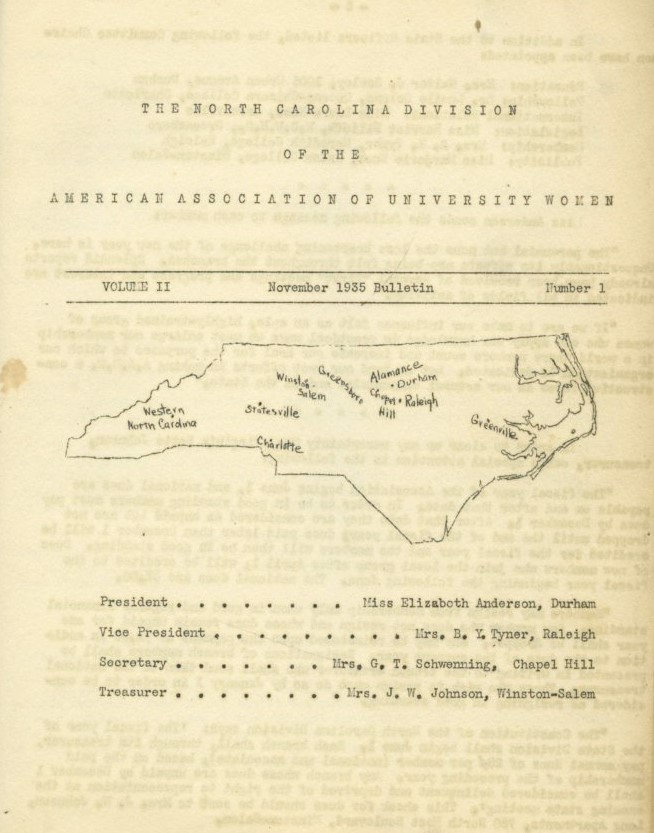

Legislative Chairman, Miss Harriet Elliott, September 25, 1935

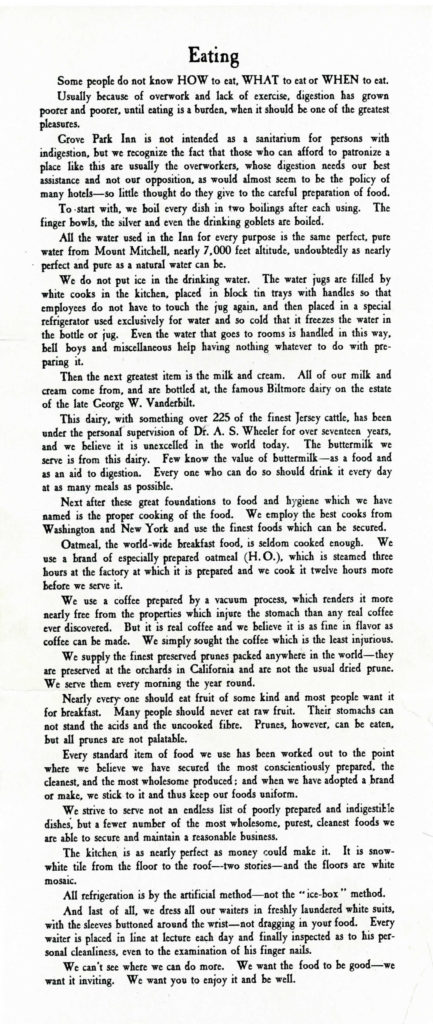

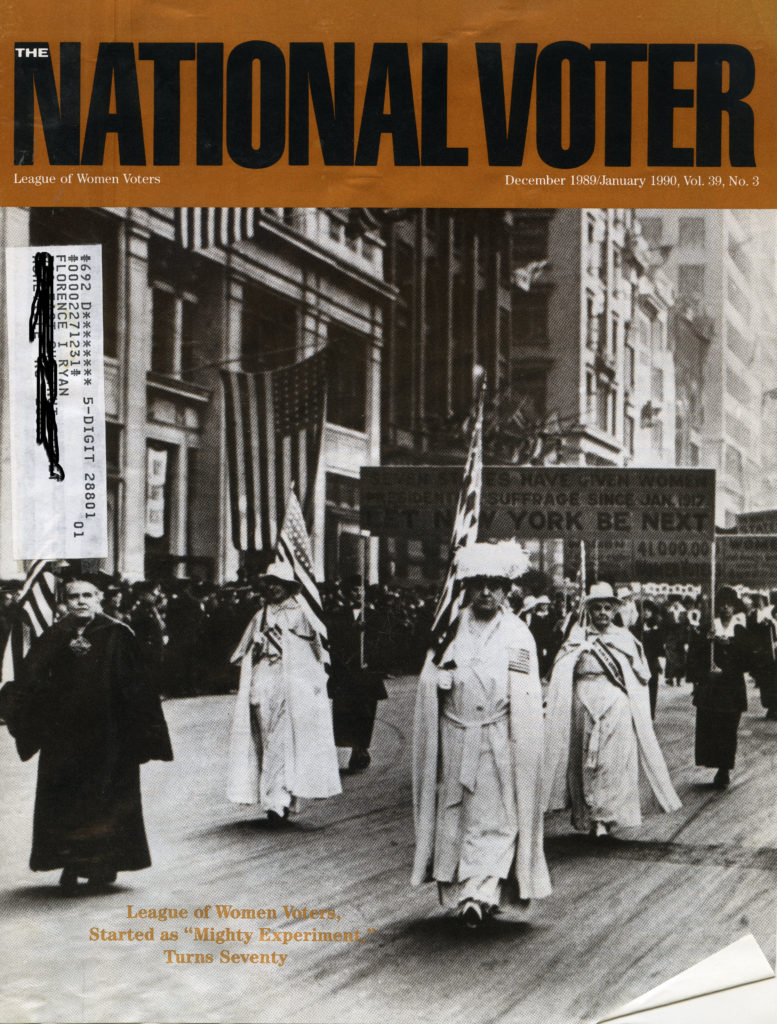

On November 28, 1881, with light snow falling in the chill air, 17 college graduates from eight colleges met in Boston to discuss the need for an organization related to higher education. At this point in history a plethora of college groups and societies related to higher education existed- the honor society Phi Theta Kappa was founded more than a century prior to when this meeting occurred. So why the need for another college organization? What was so interesting about this particular group of people who were meeting to discuss it?

They were all women.

The group was led by Marion Talbot and Ellen Richards, and their goal was to increase higher education opportunities for women through the formation of an organization devoted to women scholars. They would name their organization The Association of Collegiate Alumnae. By January 14, 1882, the organization was formally established and they would release their first research report establishing that women’s health was not adversely affected by attending college- a rather novel idea at the time.

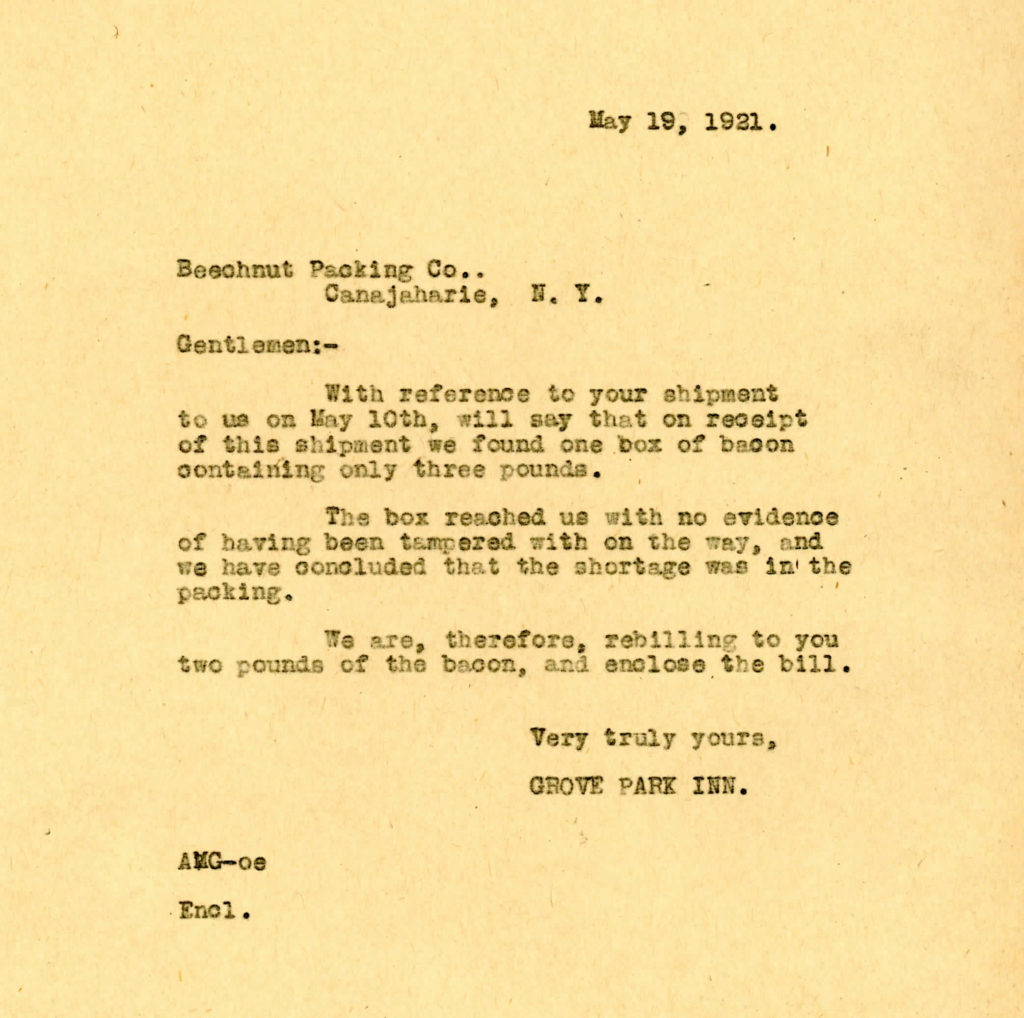

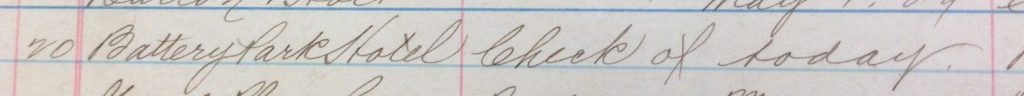

The Association of Collegiate Alumnae would go on to release several additional reports- a gender-based salary study in 1907, followed by a report presenting evidence that women during this time period were paid 78 percent of what men similarly employed were earning. By 1921 the Association moved into its new headquarters in Washington D.C., a mere two blocks from the White House, and continued to remain active in current events affecting women.

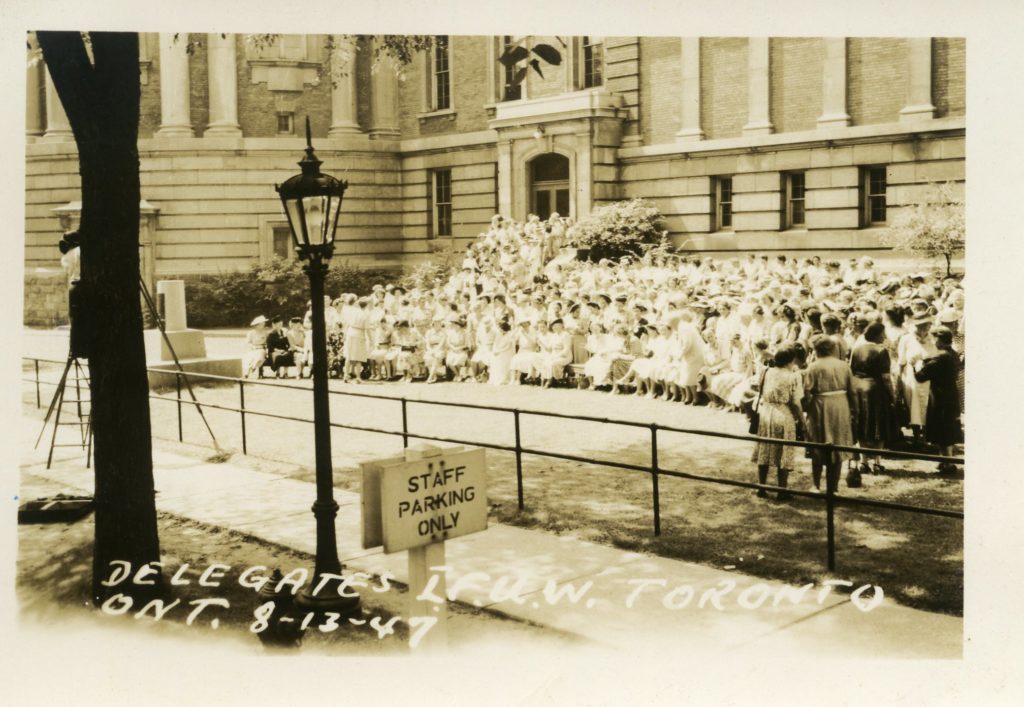

Later that same year, the Southern Association of College Women formally merged with the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, creating the American Association of University Women, or the AAUW. Today the AAUW is a non-partisan, non-profit organization whose members promote equity for women and girls through education, research, and advocacy. The AAUW comprises over 170,000 members, with over 1,000 local branches and 800 participating college and university members.

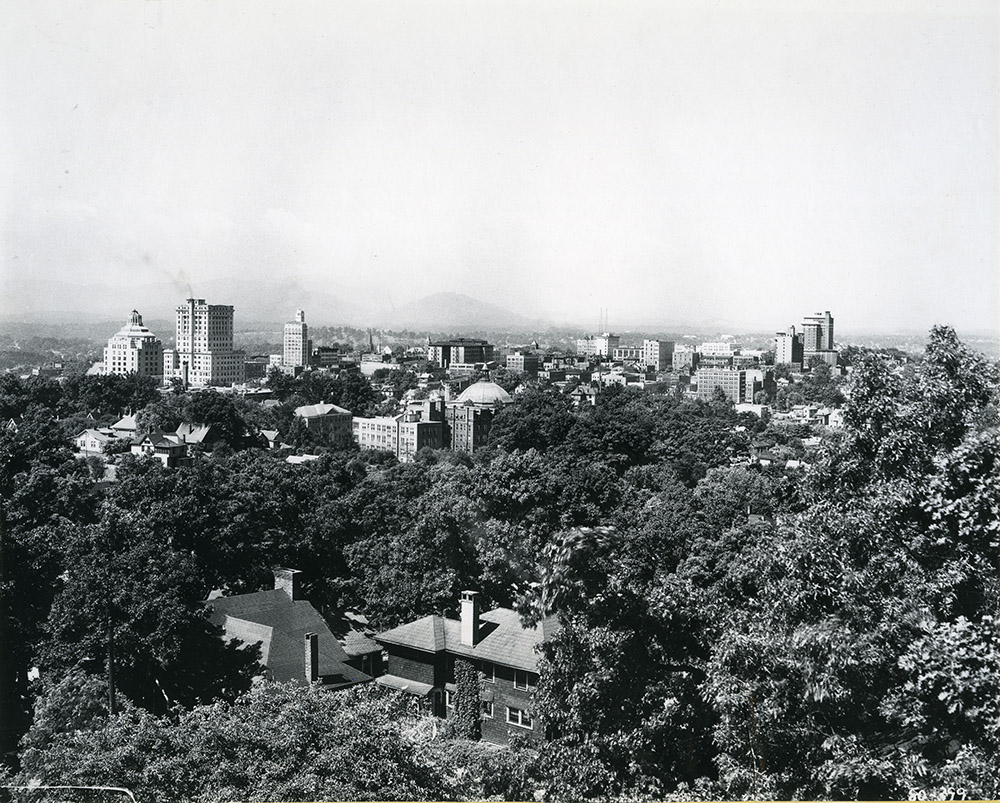

Closer to home, the Asheville Branch of the American Association of University Women has a similar and equally storied history. Founded in 1915 by sixteen female college graduates, this branch of the AAUW is the fourth oldest branch in North Carolina. These women organized the Western North Carolina Branch of the Southern Association of College Women, which merged with the AAUW in 1921.

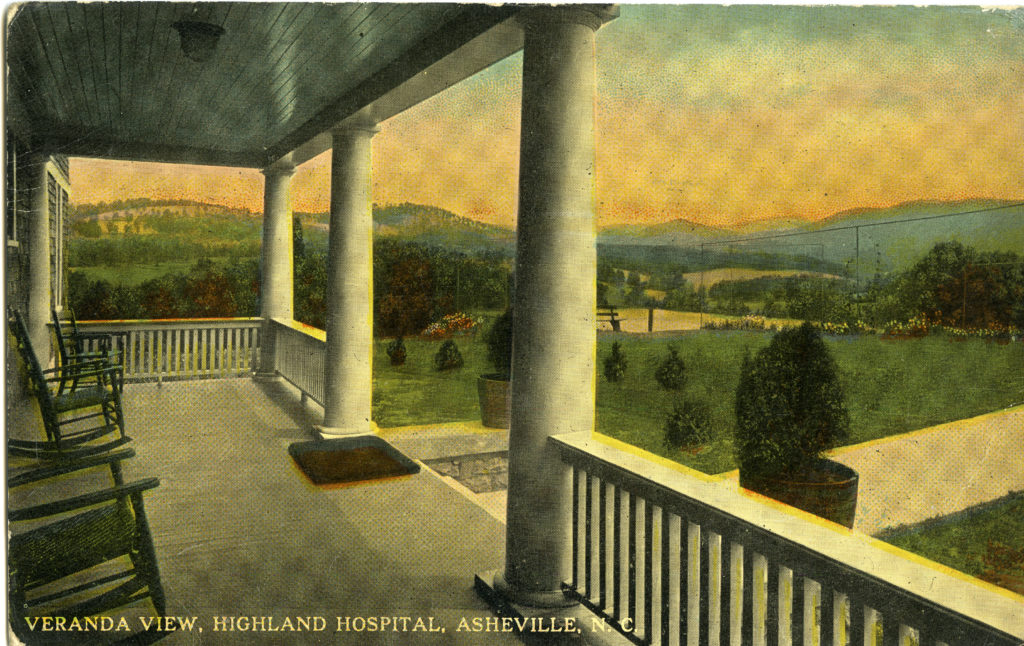

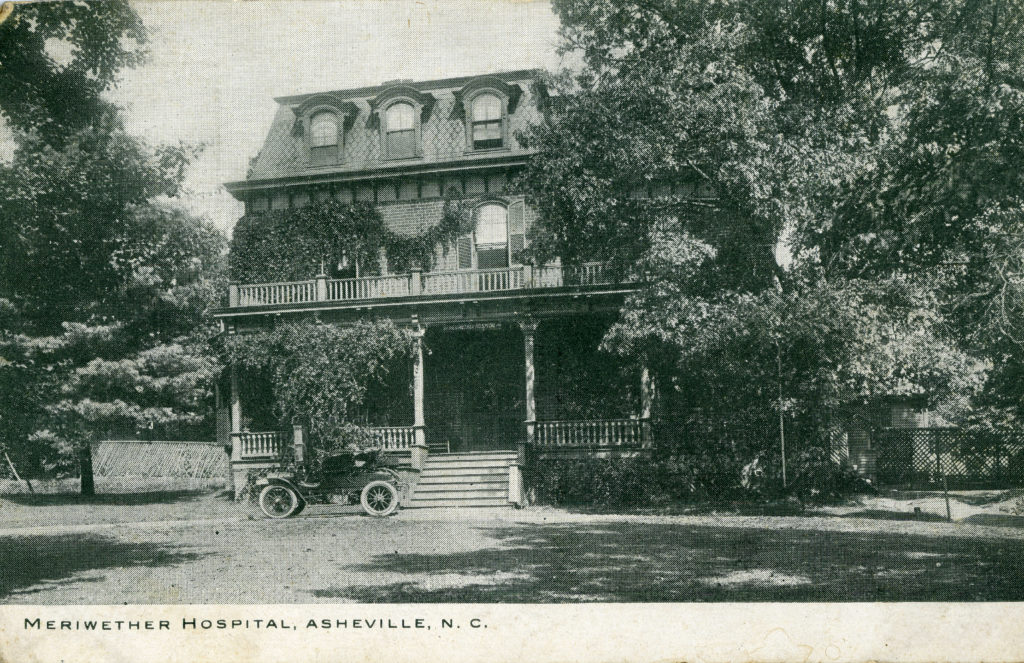

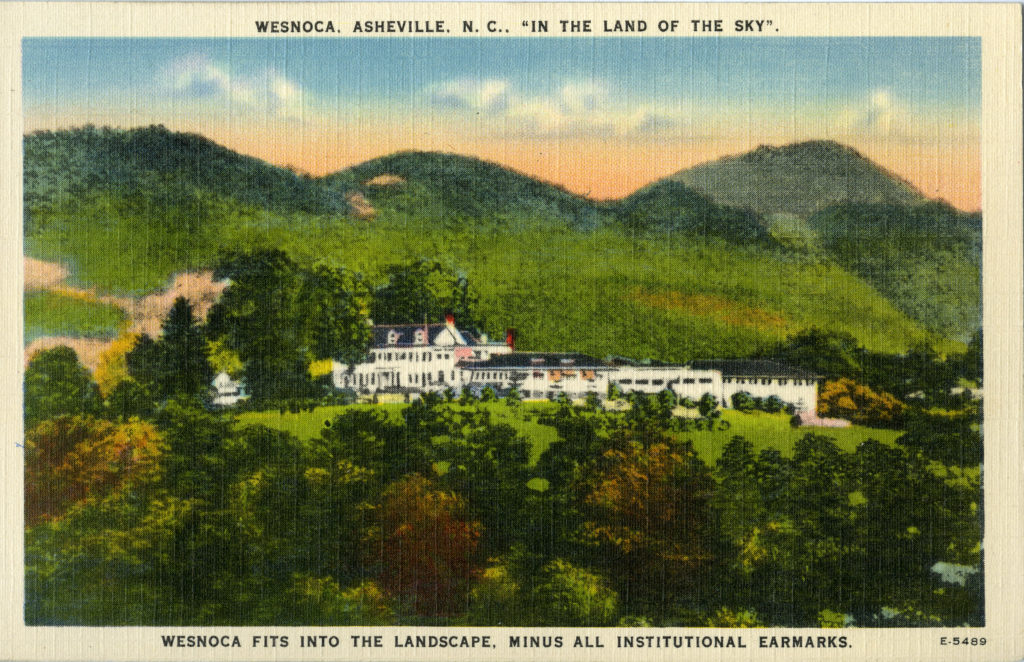

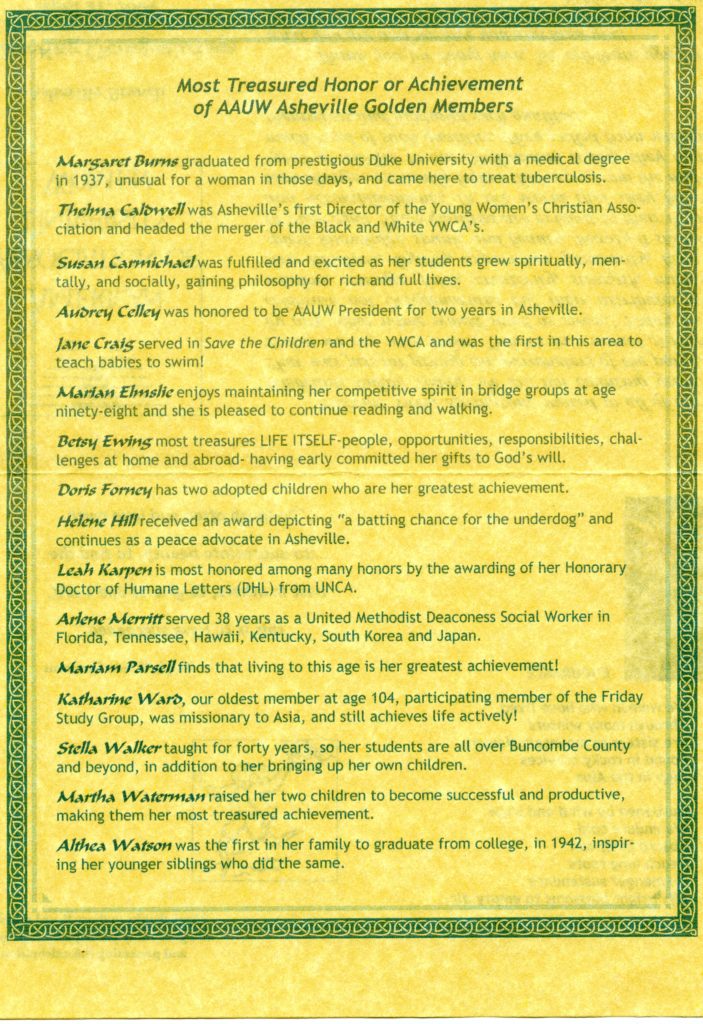

The North Carolina Branch of the AAUW tackled community projects from the outset, including assisting with the Salvation Army and visiting patients in local sanitariums. Women’s education remained at the forefront though, and members established night schools and helped set up the public library. The membership rolls of this local branch of the AAUW contains an abundance of Asheville women who were instrumental in making significant inroads for women and girls in Western North Carolina.

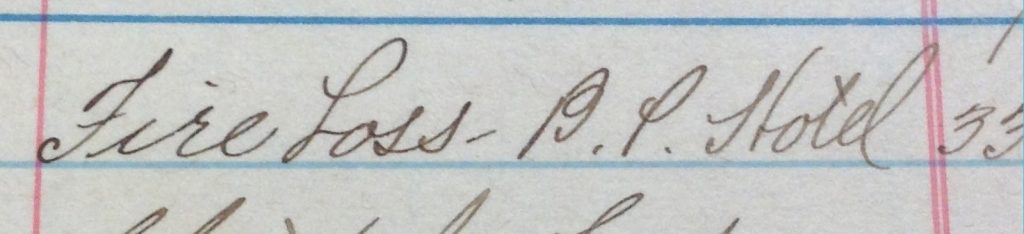

Indeed, the Asheville AAUW’s History in the area showcases various projects through the decades, from helping set up a juvenile court system to aiding refugees of World War II with their Refugee Shop. The Shop netted over $20,000 in its first year and was so successful that it continued to operate for thirty more years. The Refugee Shop did not go unnoticed on a national level either- the Asheville Branch of the AAUW received the US Treasury Award for the Shop in 1943.

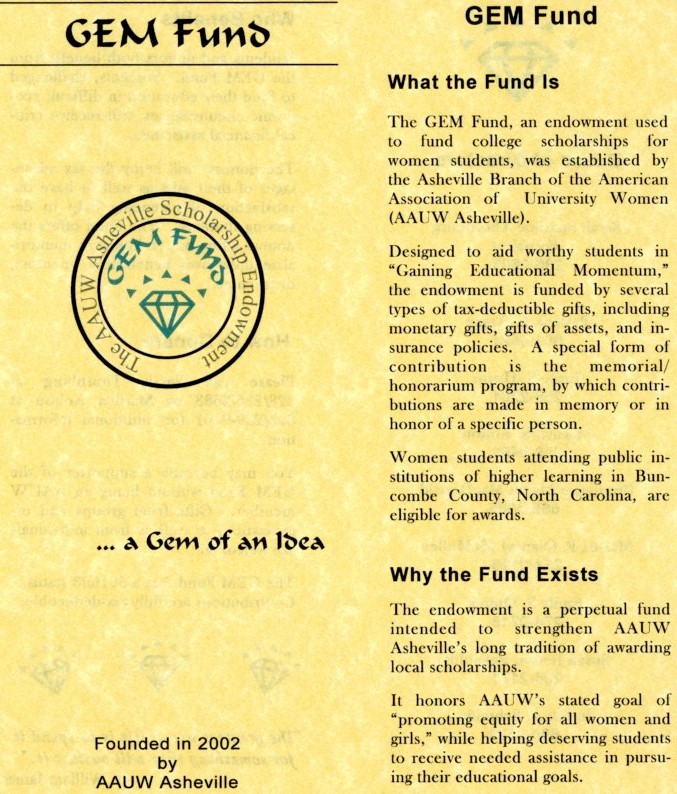

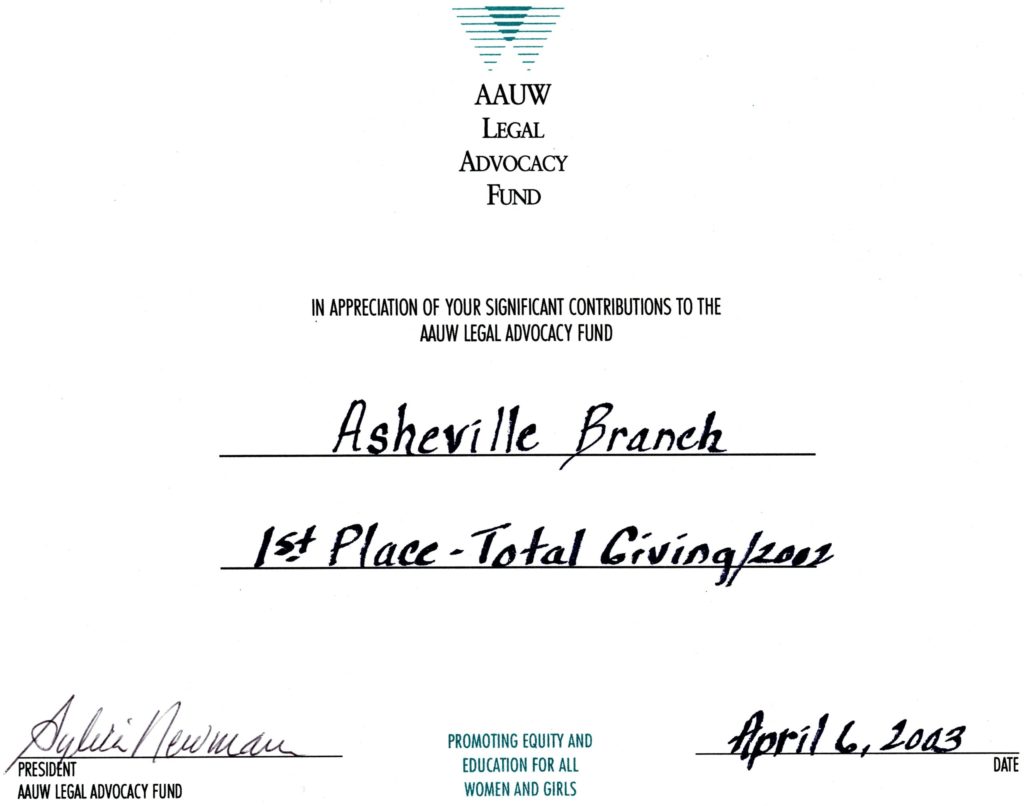

The AAUW Chapter of North Carolina boasts many impressive achievements throughout it’s history, including their Women in History project, which provided local elementary schools’ fifth grade classes with a viewpoint of History from a woman’s perspective. In 2002, the branch inaugurated their GEM Fund- Gaining Educational Momentum, a 501 (c)3 non-profit endowment for local scholarships for women whose education was interrupted or postponed. They have awarded over $160,000 in scholarships to date, in order to help women achieve their educational, employment, and research goals.

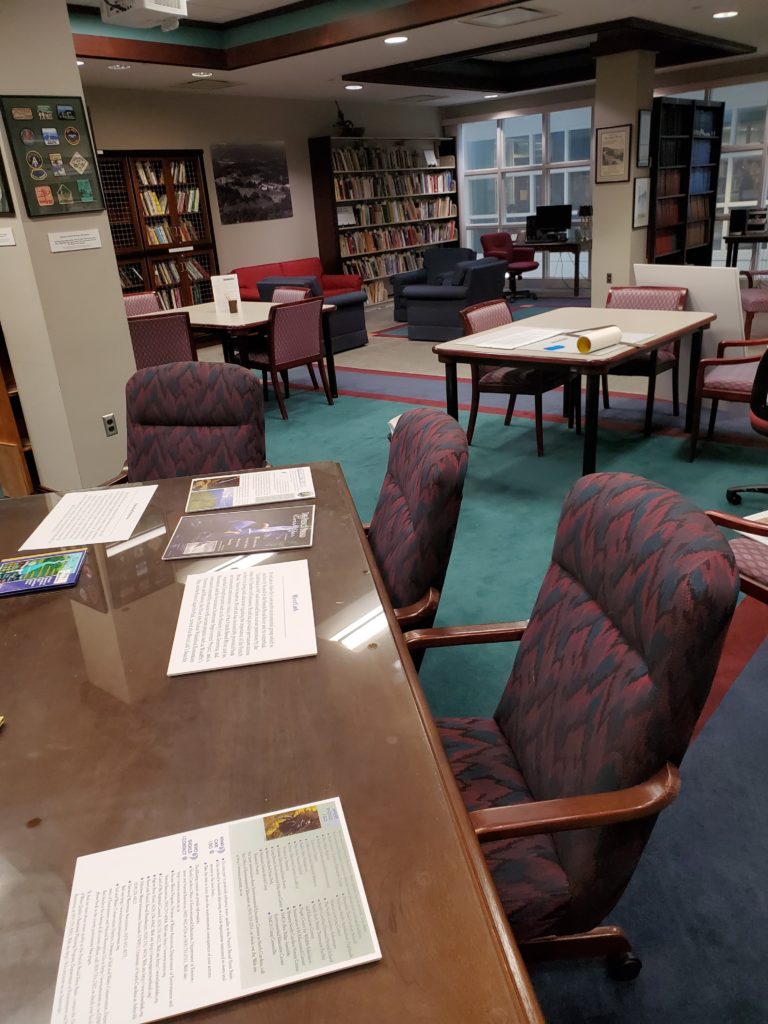

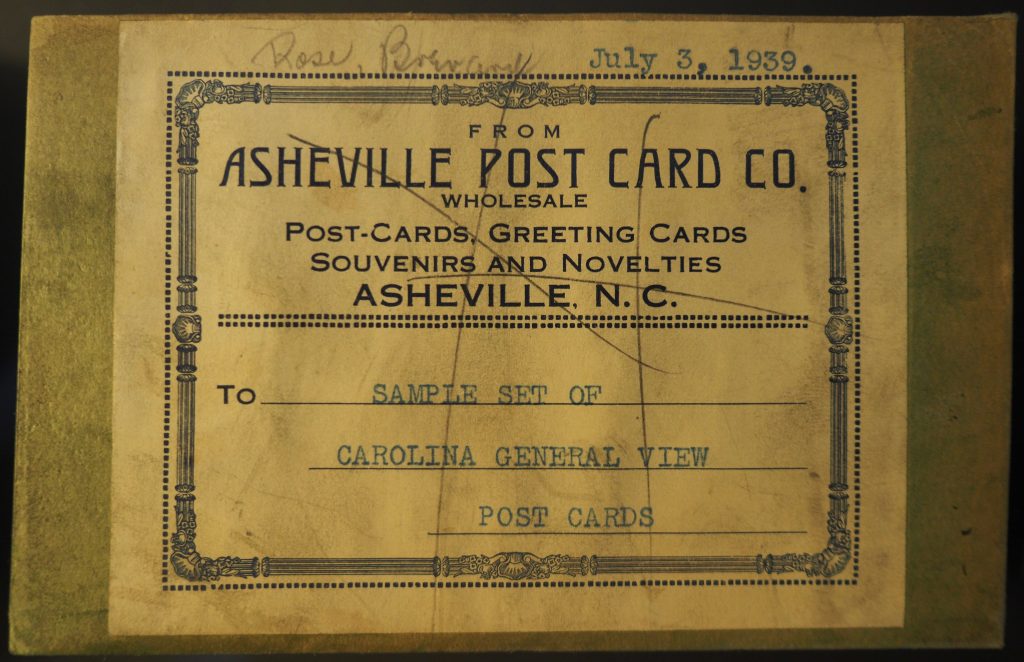

The Asheville Chapter of the AAUW continues to grow and maintain their ongoing commitment to AAUW’s mission. Here at UNC Asheville’s Ramsey Library Special Collections, we are honored to hold their archives and consider their collection an instrumental addition to part of our mission of documenting and preserving the significant achievements women have made in Buncombe County and Western North Carolina.

Today marks UNC Asheville’s Fall 2019 Commencement for its winter graduates, and it is collections like the American Association of University Women which remind us that education is, and should remain, a pathway to a brighter future for all that wish to seek it.

On that note, we would like to wish our graduates “Good Luck!” today and always, as well as a very Happy Holiday to all of you from Special Collections! We will see you all in the New Year!

Bibliography

American Association of University Women, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina Asheville, 28804.

asheville-nc.aauw.net

www.newspapers.com, The Boston Globe