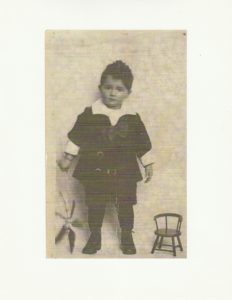

In honor of Yom Hashoah, the Israeli Holocaust Remembrance Day, as well as the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, we are continuing our Remembering the Holocaust project. This project pulls from two different collections at Ramsey Library Special Collections, Choosing to Remember: From the Shoah to the Mountains and The Sharon Fahrer Holocaust Collection, to explore, honor, and celebrate Holocaust survivors. This is the third installment in the series. John Rosenthal was a young boy from Cologne, Germany when the Nazis took over. John had a long journey before he and his family finally came to the United States, where they finally found a home.

A Tumultuous Journey

John Rosenthal’s Story

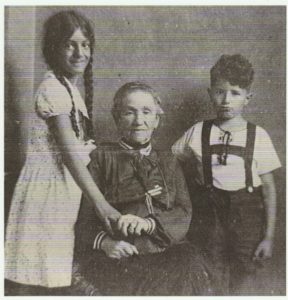

Individuals experienced the Holocaust differently. For Frederick John Rosenthal, a young boy from Cologne, Germany, it began with being sent off to Holland. John’s parents, recognizing the growing tensions in 1933 with Hitler’s rise to power, thought it would be best to send John and his brother, Max Adolph, somewhere they would be safer. John and Max’s move to Holland was the first of many moves within the span of a couple of years. Because of constantly moving—much of which was to other countries—John’s education was interrupted. At times learning was extremely difficult due to language barriers.

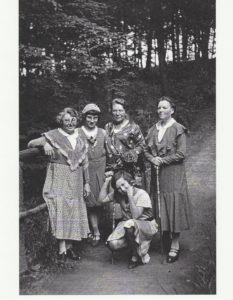

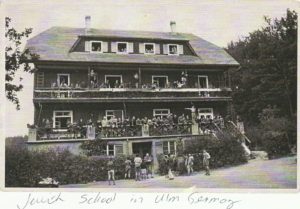

John recalled one place, Landschulheim Herrlingen, in particular as extremely pleasant. Landschulheim Herrlingen was Jewish boarding school in southern Germany near Ulm. Located in the countryside, not far from what would later be the home of German General Erwin Rommel, Herrlingen provided John and his brother with a “beautiful education” that included music and crafts. However, Herrlingen was also short lived for John. One day, while jogging through the woods, John started limping and fell behind the others. It was discovered that John had contracted Polio and had to return home to Cologne. Back in Cologne John was given all sorts of treatments, from hydrotherapy to electroshock, and had to take two aspirins every night before bed just so he would withstand the pain enough to sleep. What helped the most, John remembered, is his father rubbing his thighs with extract of “bee poison” every night, which “had the effect of increasing blood circulation.” By this time things were tough for Jews in Germany. Jews could no longer attend German public school, go to the movies or opera, or even sit on park benches. “Everywhere you went and looked there were signs, ‘Juden unerwuenscht,’ or ‘Jews not wanted here.’” John also recalled kids chasing after him and throwing stones at him, yelling “Jud, Jud.”

As things continued to worsen, the Rosenthals began to consider emigrating. They looked to friends in England and the United States for help. John’s father had to sell his business before they could leave. The buyer ended up being a former employee and friend of the Rosenthals who had joined the Nazi party. She bought the business for only 1/3 it’s actual worth. In the meantime, things were rapidly deteriorating for Jews. Daily life included things such as open trucks “filled with Nazi brown shirts, driving through the streets singing their Nazi songs, ‘When Jewish blood spurts from the knife, things go twice as well.’” Then came Kristallnacht.

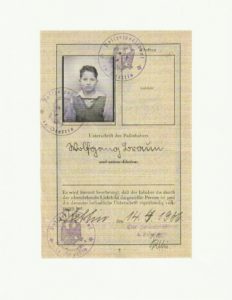

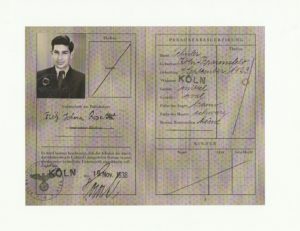

On the morning of Kristallnacht, John’s father had left to go to the police headquarters to pick up their passports so they could leave for America. After being warned by friends about what was happening, he quickly returned home, gathered up his family and some provisions, and the Rosenthals hid for three days in the top story of their apartment building, among the washers and dryers. The Rosenthals all survived, although the Jewish high school and their synagogue did not.

The Rosenthals were finally able to leave Germany—though not before they paid part of the Judenbusse, the penalty Jews were required to pay for a murder of a German diplomat by a Polish Jew, which was the official reason for Kristallnacht—so they headed to Switzerland before continuing to the United States. The elder Rosenthals had thought ahead and sent much of John’s mother’s jewelry and handmade dresses out of the country. These would provide them with a source of income once they were free from Germany.

The United States was a time of acclimation for John, who had to learn a new way of speaking and dressing. “…the English I learned was the King’s English and of course I was made fun of in school. Also, I wore short pants, which also were made fun of, so the two quickest acclimatizations were dropping the King’s English and dropping the pants to full length.” John’s parents continued moving the family around until John’s mother’s business was finally reestablished in New York City, where it became quite successful and included customers such as Saks Fifth Avenue, B. Altman, and Henri Bendel, and more. John helped out with the business by taking charge of all the incoming and outgoing correspondence. The United States was also where John received his first degree through a business school in New York.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, John was drafted into the United States Army where he was sent to the University of Minnesota as part of an Army Specialized Training Program. It was on his journey to Minnesota that John stopped off in Asheville, where he later returned to live.

John had a long, tumultuous journey before he and his family finally found a home. He is a reminder of the great lengths to which parents would go to keep their children safe, even though “safe” was a hard place to find during these trying times. The elder Rosenthals used every mean with in their capabilities to rescue their family from a terrible fate that many others were not fortunate enough to escape. Despite difficulties John faced, and perhaps even in defiance of the abuses John and his family experienced at the hands of the Nazis, they did finally find a safe place to call home.

John’s story is part of the Choosing to Remember: From the Shoah to the Mountains collection at D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, located at the University of North Carolina Asheville. This collection is a compilation of oral histories of Holocausts survivors. For more information on John and other survivors’ stories, visit Ramsey Library Special Collection’s online finding aid.

If you are interested in exploring more Holocaust survivor history, please see our newly processed collection, the Sharon Fahrer Holocaust Collection.

-Kristen Byrne