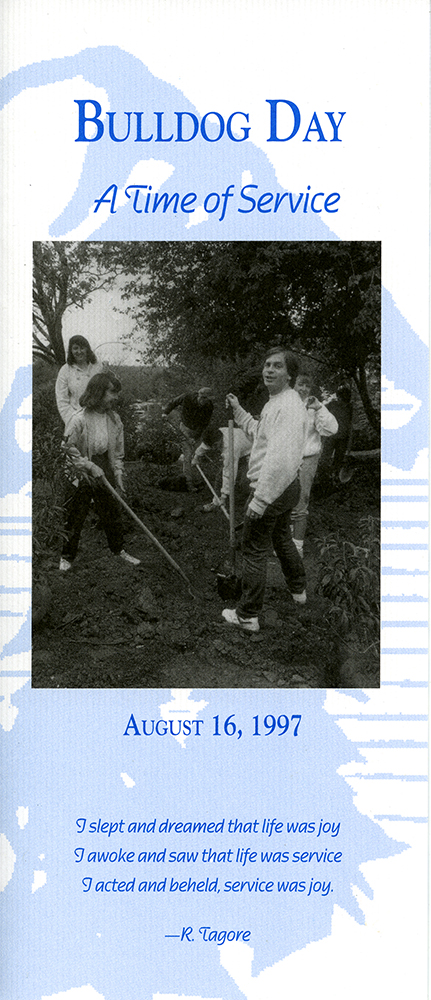

In 1997, UNC Asheville held its first Bulldog Day. The event was part of new student orientation, and was described as, “an ambitious program to initiate each of our new students into the culture of service and concern.”

The activities were organized through the freshman colloquium, and Sarah Bumgarner, who was then supervisor of the colloquium, came up with the name Bulldog Day.

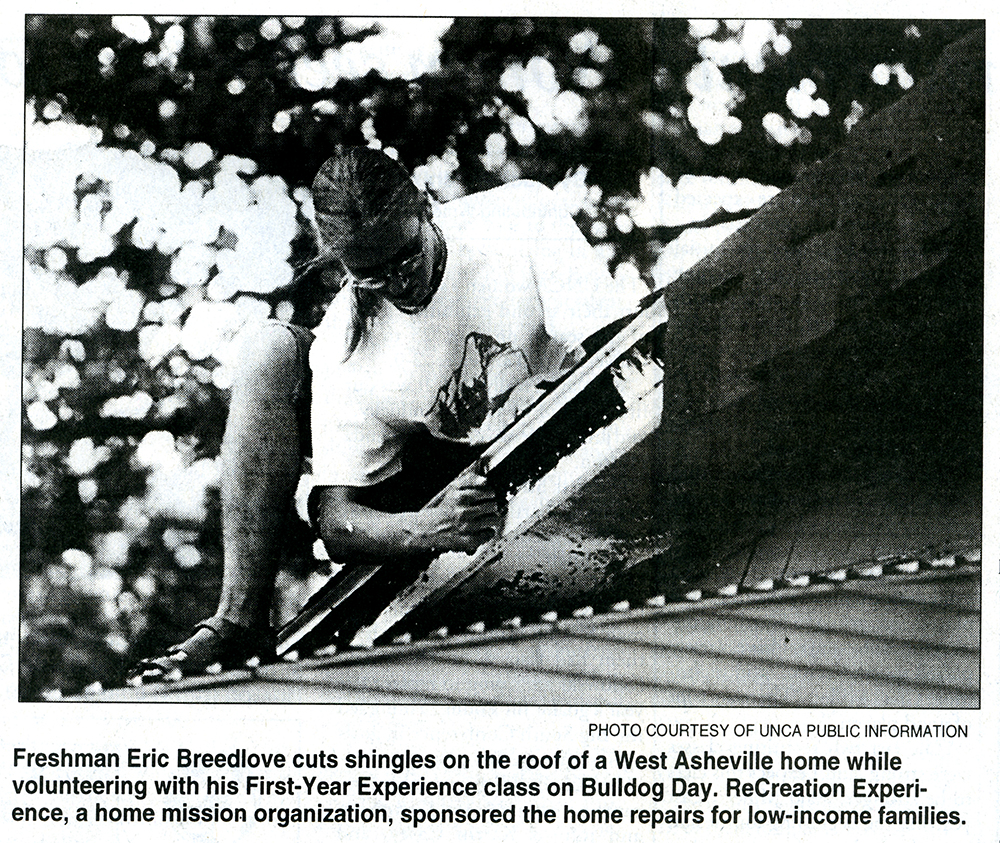

The Blue Banner subsequently reported that more than five hundred freshmen and first year students served at 27 sites in Buncombe County. Activities that year included sorting and bagging food at Manna Food Bank, clearing trails, working with RiverLink to clean up the banks of the French Broad, and repairing a home for a Meals on Wheels recipient.

The Asheville Citizen-Times wondered if the program “defied a popular myth that young college students are detached from the community around them”. The newspaper also noted that community service had long been a requirement at private schools, and thought that UNC Asheville was part of a growing trend for similar initiatives at public universities.

This theme was echoed by one of the organizers of that first Bulldog Day, UNC Asheville Professor Merritt Moseley. He wrote about the university’s long history of service to its community and state, and that while it was a public, secular university, it maintained the same aims of a rich intellectual life and dedication to high quality learning as “more expensive counterparts in the private sector.” He explained that the university wanted students to “learn by practice,” and noted George Elliot’s observation that “the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts.”

Chancellor Reed declared the initial Bulldog Day “a tremendous success,” and that it would be a focal point of orientation in 1998. That year’s projects included, clearing poison ivy from Kenilworth Cemetery, giving a party for children at Hillcrest HeadStart Center, assisting in the rehab of a former drug house, and helping to establish an urban garden. Additionally, students continued to work with agencies, such as RiverLink, Manna Food Bank, and Meals on Wheels who had been involved the previous year.

On Bulldog Day 2001, students worked at the YMI for the first time. They toured the facilities, and then created a mural in the auditorium from their impressions.

By 2005, Bulldog Day encompassed teams of students, and faculty/staff leaders, working across Asheville and Buncombe County, helping organizations “from the Asheville Art Museum to the YWCA.”

Martin Luther King Jr. Day is a still a day of service for UNC Asheville, with student and employee volunteers spending their day off engaging in service to the community. For the 2017 Martin Luther King Jr. Day of Service, UNC Asheville and Mission Health teamed up, with volunteers from the two institutions helping to, build homes, work with young people, older adults and family caregivers, care for rescued animals, clean up trash, and plant trees.

Although it has gone, Bulldog Day did have lasting impacts. For example, in 2014, a Blue Banner story about the South Asheville Colored Cemetery Project featured UNC Asheville History Professor Ellen Holmes Pearson. The newspaper reported that, Pearson “became involved [with the cemetery project] 10 years ago through the now-defunct Bulldog Day of service,” and that she was a regular volunteer, as well as “visiting with student groups a few times each year.”

Colin Reeve, Special Collections

Special thanks to Prof. Emeritus Merritt Moseley for contributing much appreciated information about Bulldog Day.