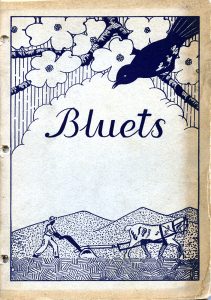

A directive by Virginia Bryan for students in her literature class at Buncombe County Junior College to write their own philosophies in verse, prose, play, or editorial, resulted in two creations that are still evident at UNC Asheville today. The first was a Creative Writing course being added to the curriculum, the second was a literary magazine to publish the students’ work.

Bluets, was first published, we believe, in the spring of 1929, and initially contained mostly poetry. Indeed, its name, which had been chosen in a contest, came from a poem by John Charles McNeill, that was included on the flyleaf of early editions. Writing in 1977, Virginia Bryan recalled how the first edition was produced with “much encouragement and no money,” and that students “secured a few ads to pay for early publications.” In the first edition, these ads were for a life insurance company, three cafes, a Chinese restaurant, and a shirt shop.

The content soon expanded beyond poetry to include editorial comment, stories, book reviews, biographical sketches, articles about local places (e.g. Biltmore Estate, and Grove Park Inn), and interviews by the students with people such as Thomas Wolfe’s sister, and the wife of O. Henry.

Although initially described as a “Literary Magazine”, in 1935, Bluets began to be described as, “A Literary Magazine Dedicated to the Expression of Progressive Undergraduate Opinion,” probably to reflect the expanded content.

Until 1944, the cover art of each edition was different, with designs often being developed from ideas in the Creative Writing class.

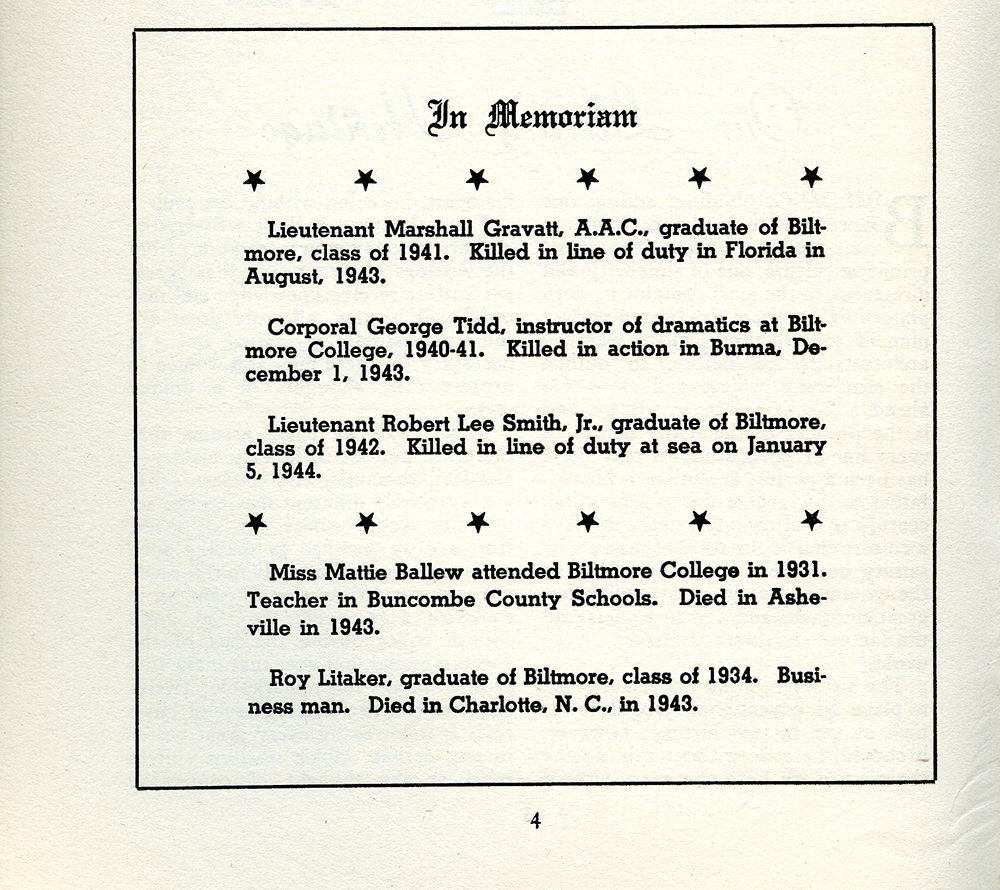

Editions published during World War II included tributes to students killed in action, and, not surprisingly, wartime articles generally took on a more somber tone.

Any student at the college could submit work for inclusion, and the editorial board would decide which to accept or reject.

Many of the students who had work published, would go on to make a name for themselves after leaving college, and not always in the field of literature. For example, the first edition of Bluets included work by Gordon Greenwood who, among many other civic contributions, served in the NC House and on the board of UNC Asheville. Another contributor was Dorothy Post, who provided works to the magazine and served as Associate Editor in the mid-1930s. She subsequently trained as a pilot and was a member of the Women Airforce Service Pilots during WWII. Post later wrote several books, and other Bluets literary alums include Gertrude Ramsey, who became society editor of the Asheville Citizen-Times, and writer John Ehle Jr., whose poetry and prose was published in Bluets in 1944.

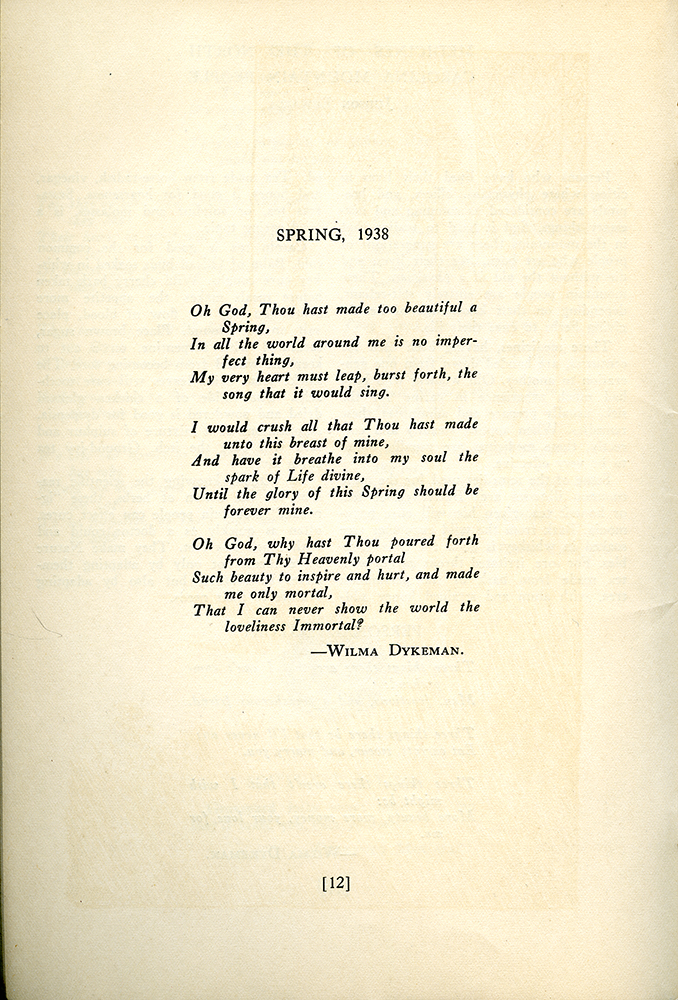

Ehle was awarded an honorary degree by UNC Asheville in 1987. Appropriately, that same year, Virginia Bryan Schreiber also received an honorary degree. Ten years later, in 1997, an honorary degree was awarded to, arguably, the locally best known Bluets author, Wilma Dykeman Stokely.

During 1937 and 1938, Wilma Dykeman wrote poetry and prose for Bluets, and served as co-editor. After graduating from Asheville-Biltmore College, she went on to write radio scripts, short stories, magazine articles, and books, including The French Broad and The Tall Woman. In 1985, she received the North Carolina Award for Literature, an award that, in 1972, had also been bestowed on John Ehle.

With such talented contributors, it is no wonder that Bluets won many awards, including numerous first place certificates from the Columbia Scholastic Press Association.

The last copy of Bluets in the archives is dated fall 1962. In The University of North Carolina at Asheville: The First Sixty Years, William Highsmith wrote that “the faculty had decided to discontinue [Bluets] because of its junior college overtones” and, “in May 1967, the first copy of Images was published.” The latter comment seems incorrect however, as there are materials in the archives that indicate Images was first published in the spring of 1964.

Images was described as “The Fine Arts Magazine of Asheville-Biltmore College,” and combined artwork with poetry and short stories. It was published until the late 1970s, (The archives has copies up to 1977), before being followed by several short-lived publications, such as Fury, The Seventh Veil, and Alchemy of the Muse.

Since the late 1990s, Headwaters has been the creative arts magazine of UNC Asheville, and it is published annually.

- Colin Reeve, Special Collections