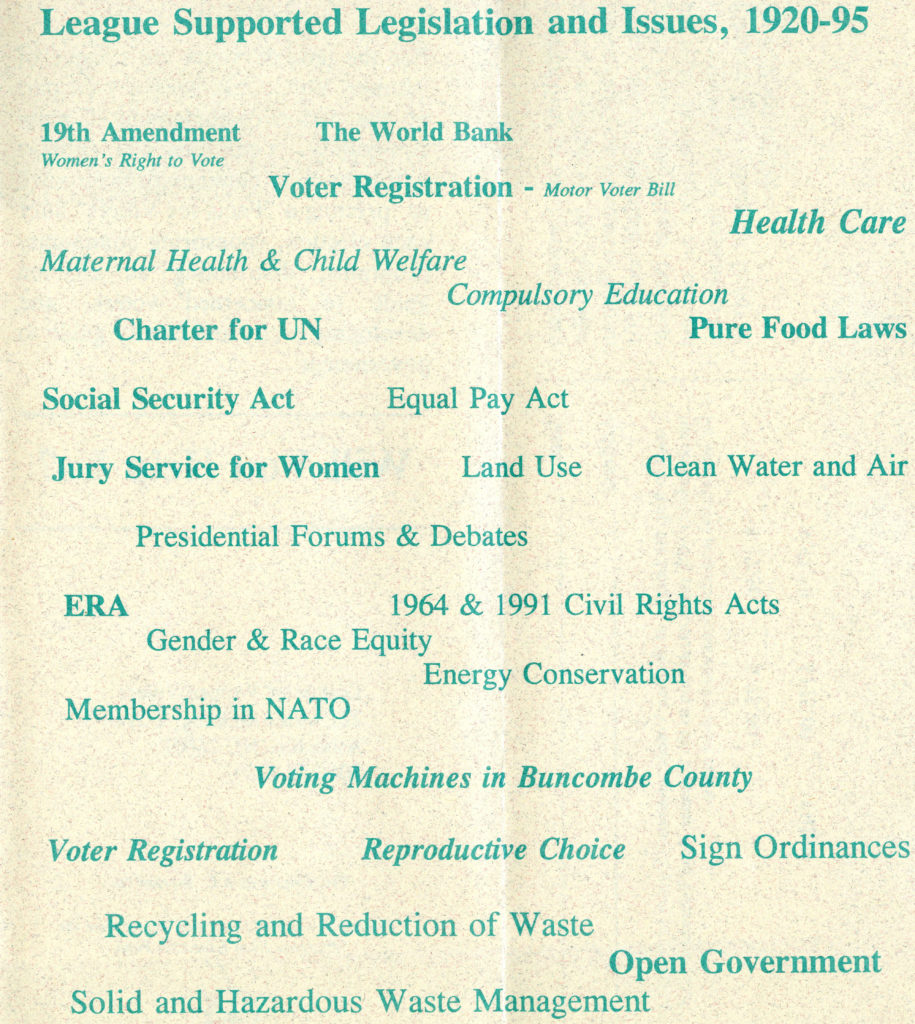

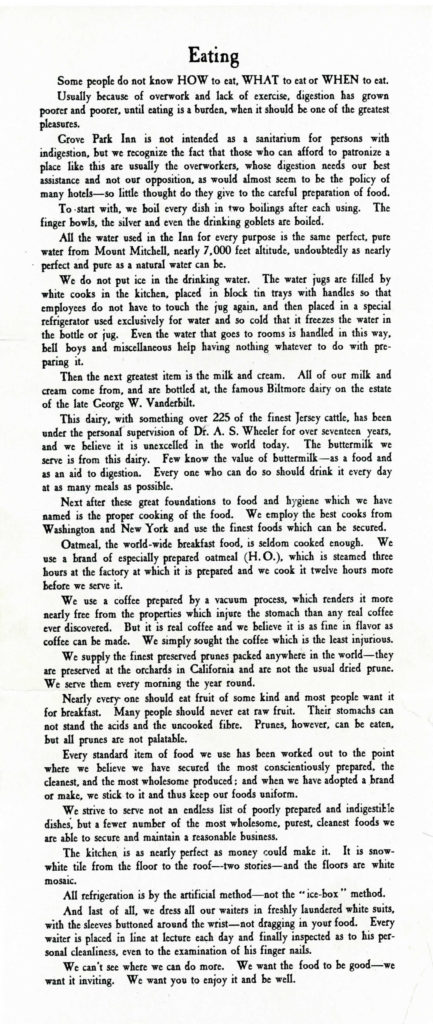

When the Grove Park Inn opened in Asheville on July 12, 1913, one of the inn’s top priorities was insuring that the food and water served at GPI was of the highest quality. They proudly described their culinary philosophy in the “Eating” section of the 1916 GPI menu below, noting that “usually because of overwork and lack of exercise, digestion has grown poorer and poorer, until eating is a burden, when it should be one of the greatest pleasures.”

It continues: “Grove Park Inn is not intended as a sanitarium for persons with indigestion, but we recognize the fact that those who can afford to patronize place like this are usually the overworkers, whose digestion needs our best assistance and not our opposition, as would almost seem to be the policy many hotels – so little thought do they give to the preparation of food.”

You could rest assured, if you were a Grove Park Inn guest in 1920, that the kitchen staff was there to prepare “the most wholesome, purest, cleanest foods we are able to secure and maintain a reasonable business.” Their culinary team was described in GPI’s literature as “the best cooks from Washington and New York.”

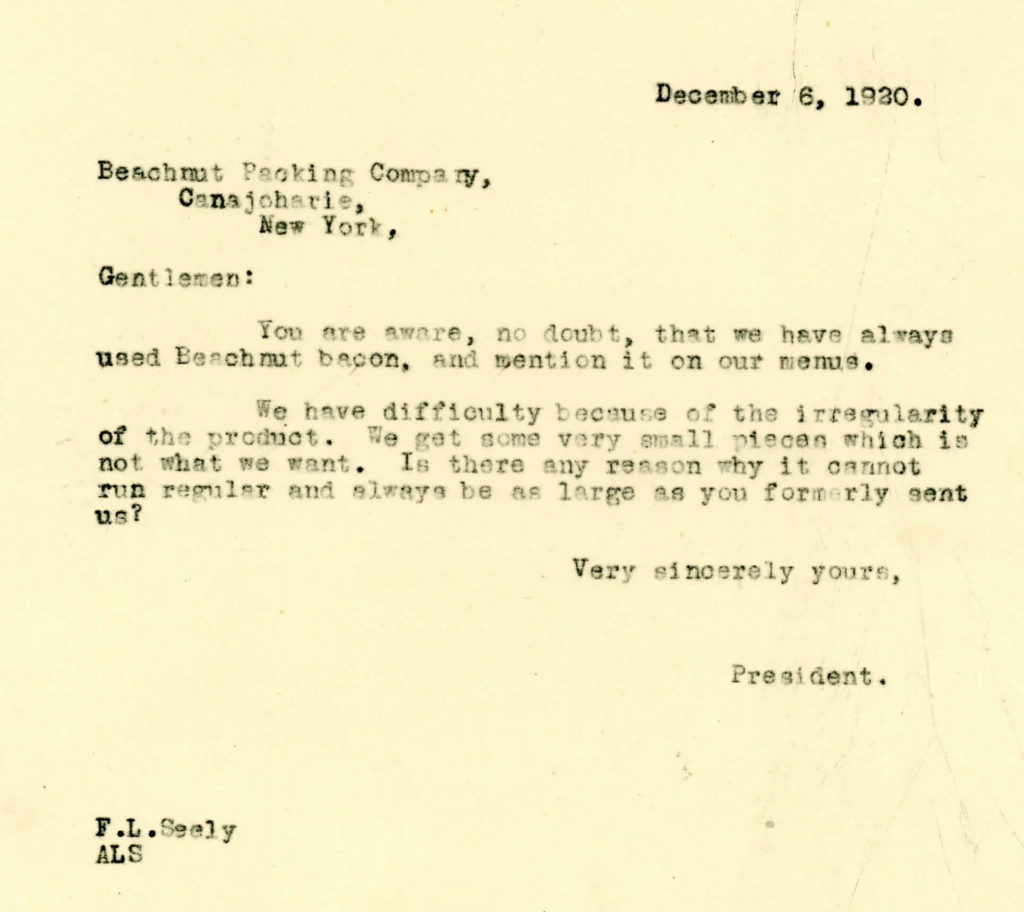

So where did Grove Park Inn secure these wholesome, pure foods? As documented in the Grove Park Inn section of the Blomberg, Patton & Grimes Biltmore Industries Archive, GPI ordered foods from a range of vendors, producers, and distributors, some local, and others from a distance. These records include nine boxes – 4.5 linear feet – of orders, correspondence, invoices, and payments for food served at Grove Park Inn. If there was a problem with an order from a vendor, it was quite common for Fred Seely himself – the manager of GPI from 1914 to 1927, and E. W. Grove’s son-in-law – to write the vendor to complain and demand redress.

Seely also had a certain amount of brand loyalty. “When we have adopted a brand or make, we stick to it and thus keep our foods uniform.” You’ll notice the list of brands on the menu above, including Heinz products and Squibb’s extracts. Sometimes, it seems, his brand loyalty eclipsed his common sense.

Which brings us to the case of the rummaged bacon.

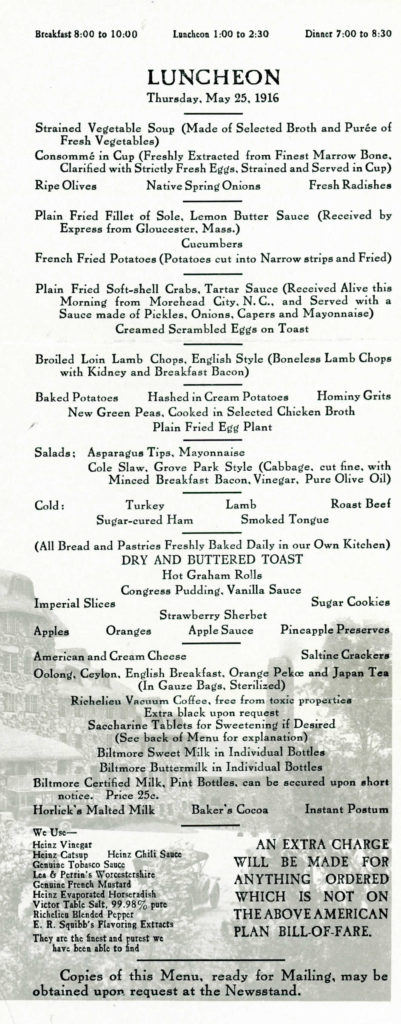

Fred Seely was fond of Beech-Nut Bacon, which was produced by the Beech-Nut Packing Company in Canajoharie, New York. Seely wrote the Beech-Nut Packing Company on December 6, 1920, declaring “you are aware, do doubt, that we have always used Beechnut bacon, and mention it in our menus.”

Between 1920 and 1926, GPI routinely ordered bacon from Beech-Nut, orders that were shipped 800 miles from mid-state New York to Asheville via railroad. These rail orders were sometimes problematic. For instance, a bacon order was shipped “express” from Beech-Nut on April 7, 1920, and when it had not arrived in Asheville by April 23, GPI notified Beech-Nut that the shipment was late. Beech-Nut contacted American Railway Express on April 23, noting that GPI in Asheville had not received their bacon, and asked the railroad to “please trace at once as they are perishable goods.” The bacon did arrive at GPI on April 28, three weeks after shipment from New York. And this wasn’t the first time this happened – a shipment in January 1920 was also late and had to be traced.

Remember, these are “perishable goods.”

And Grove Park wasn’t concerned only about shipping, but also about the quality of the bacon itself. In the letter below Seely wrote Beech-Nut in December complaining of “the irregularity of the product. We get some very small pieces which is not what we want. Is there any reason why it cannot run regular and always be as large as you formerly sent us?”

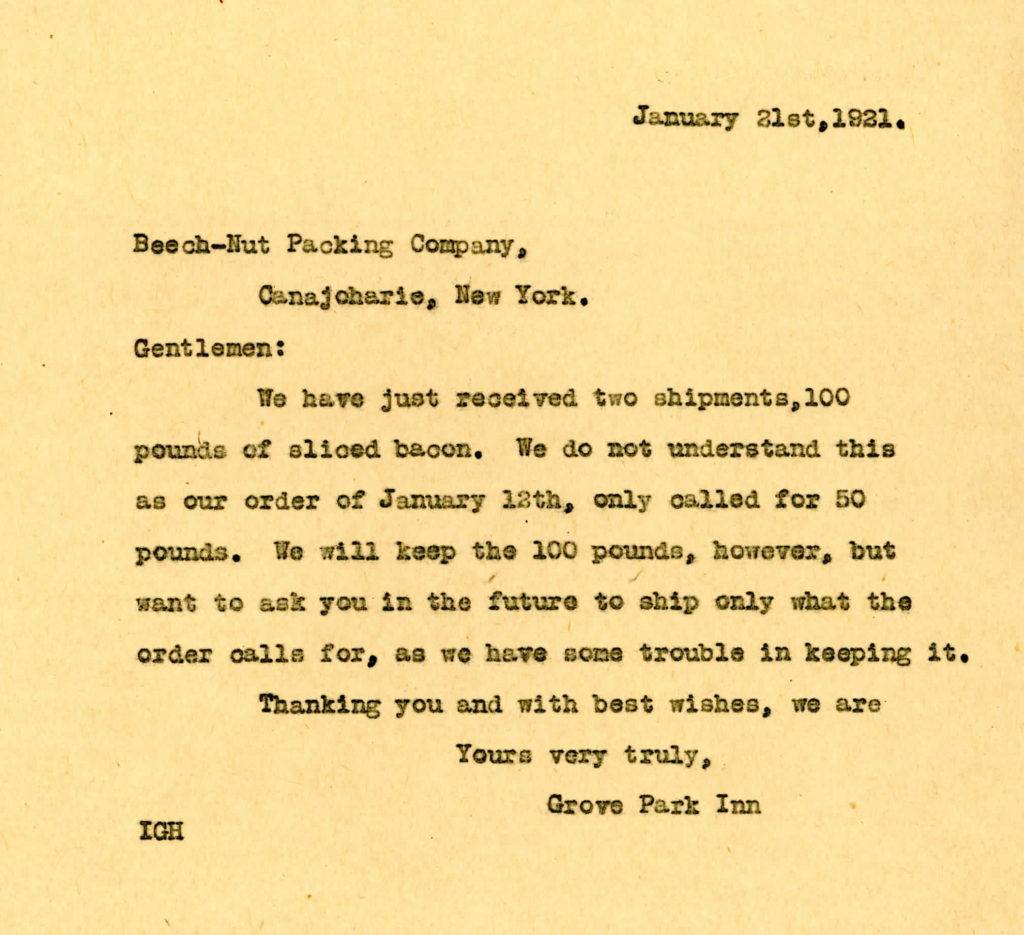

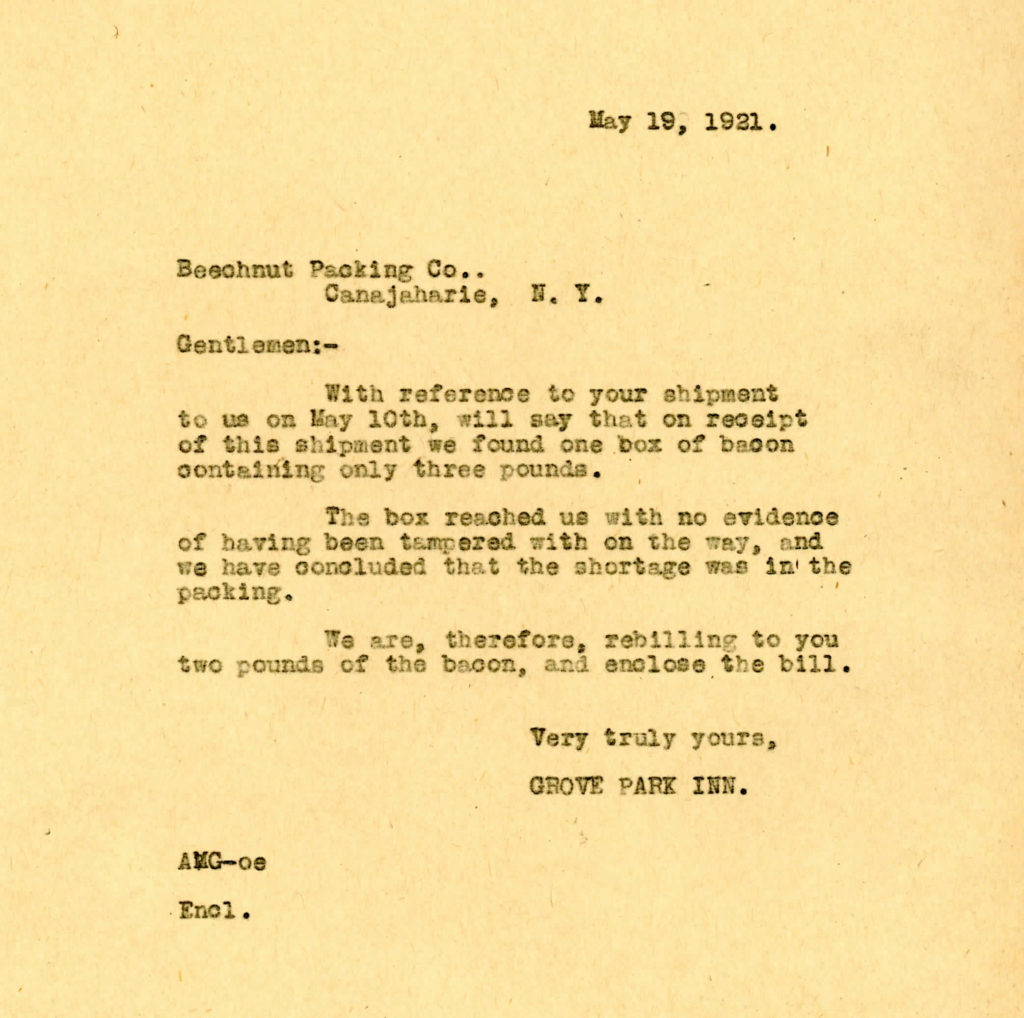

Problems in the procurement of pork products persisted, as noted when Beech-Nut shipped too much bacon:

Or too little bacon:

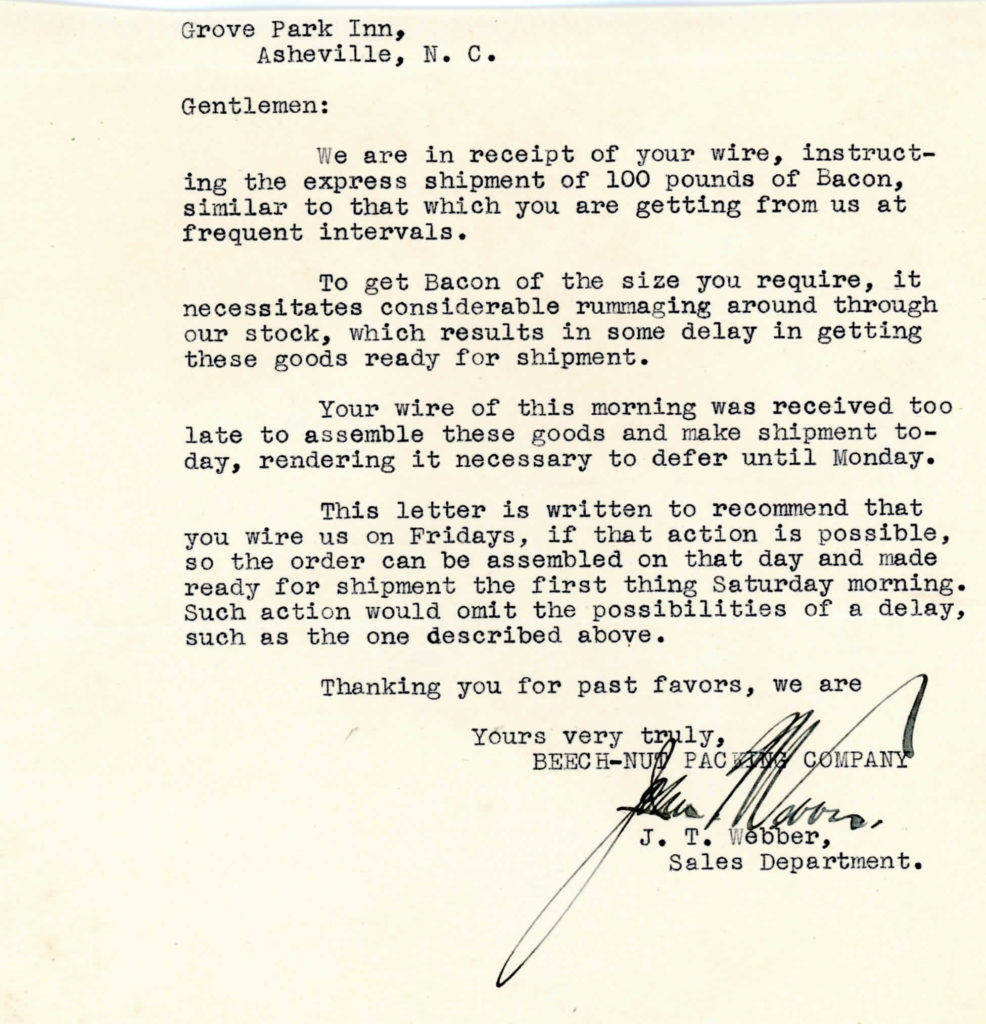

In this undated letter (from 1920 or 21) apparently GPI’s order threw normal packing operations at Beech-Nut into a frenzy. “To get Bacon of the size you require, it necessitates considerable rummaging around through our stock, which results in some delay getting these goods ready for shipment.”

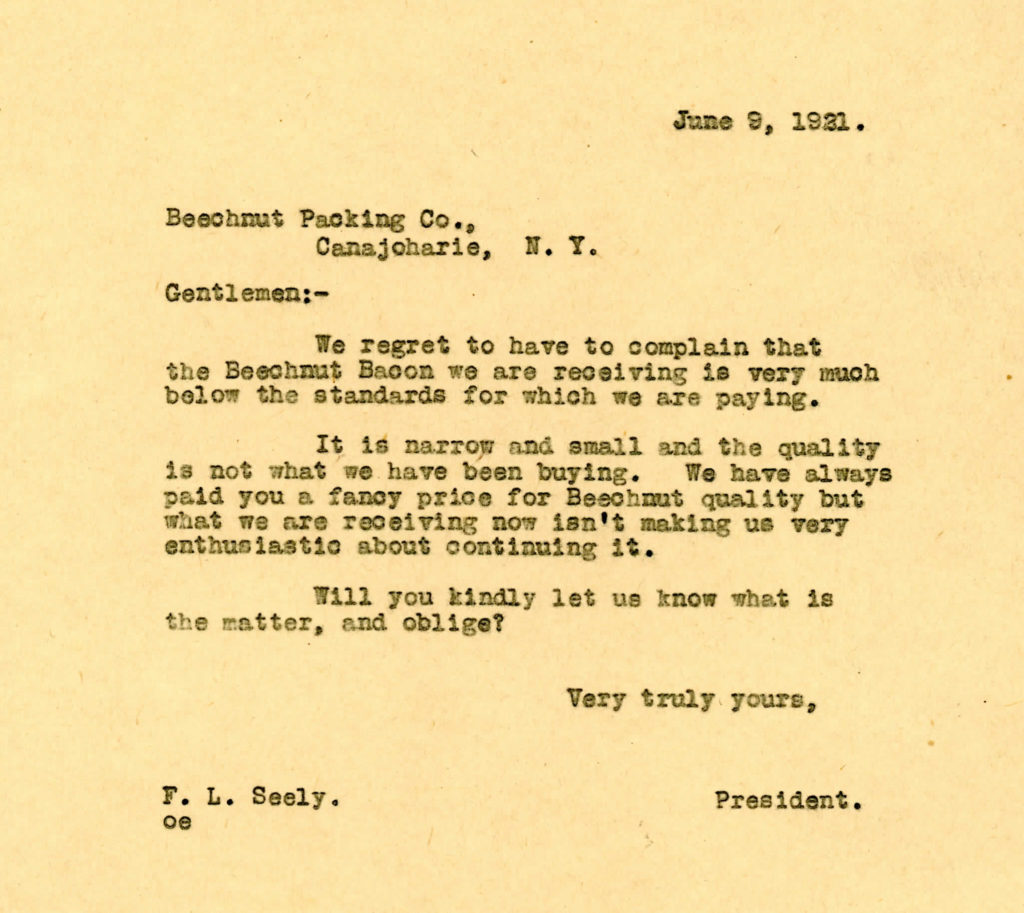

Finally, it seems that all this rummaging, poor quality, and shipping woes were too much for Seely, as he wrote in this letter of June 9, 1921, stating that “we have always paid you a fancy price for Beechnut quality but what we are receiving now isn’t making us very enthusiastic about continuing it.”

One of the questions this procurement tale begs is: why didn’t Seely try to source bacon locally? Buying pork in Buncombe County shouldn’t have been that difficult. According to the 1920 census there were over 3700 farms in Buncombe County, and farmers noted that they owned 10,074 swine. With all this locally available pork, it seems odd that Seely insisted on having his bacon shipped over 800 miles of rail lines.

To be fair, Seely did source a lot of food from local vendors. One of the largest files in the “food” section of these records are the invoices and orders with Virginia Fish & Oyster Company, an Asheville company that provided most of GPI’s seafood. Not only were they a local company, there’s no record that Virginia Fish & Oyster Company ever had to “rummage around” through their stock to fill an order.

_______________________

Collections used in this post:

The photos of GPI and the dining room are from the Grove Park Inn Photograph Collection

The correspondence is from the Blomberg, Patton & Grimes Biltmore Industries Collection

The GPI menu is from the Shirley Stipp Ephemera Collection