Changing from a two-year to a four-year college, “on the basis that there was need for an institution in the mountains which would occupy a unique place in the state systems of higher education”. An institution “stressing quality, emphasizing independent responsibility on the part of students, and stimulating the creative energies of all through effective participation”, and which subsequently gained accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.

Moving from a “college [that] had 500 students and a faculty composed mostly of part-time teachers from the community”, to one having “a faculty which would support our aims and purposes and….develop the curriculum, the library, and the entire institutional program.” The speaker also noted that “many of the professors came here with little more assurance than a hope that a fine program would emerge”. (In the fall of 1969, enrollment was 700 full time students, and 215 part-time. Around 40% of the 65 faculty listed in the 1969-70 catalog had doctorates.)

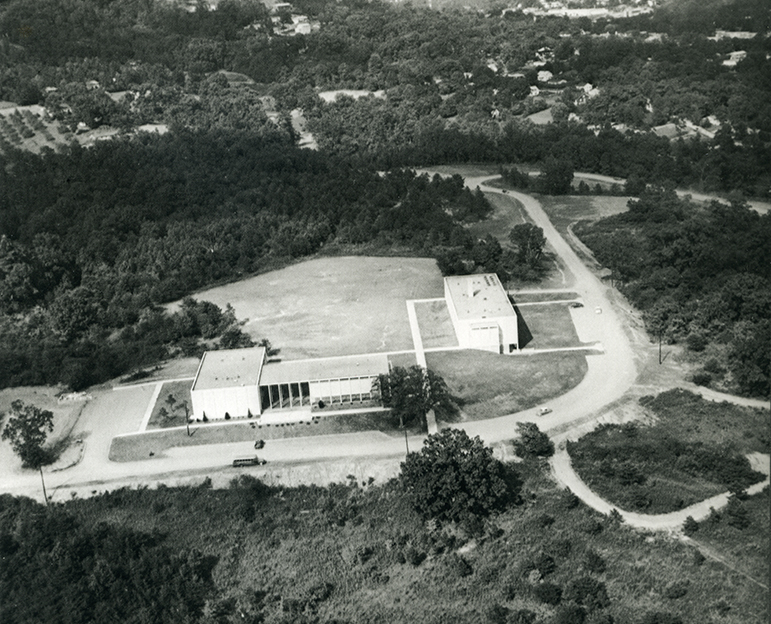

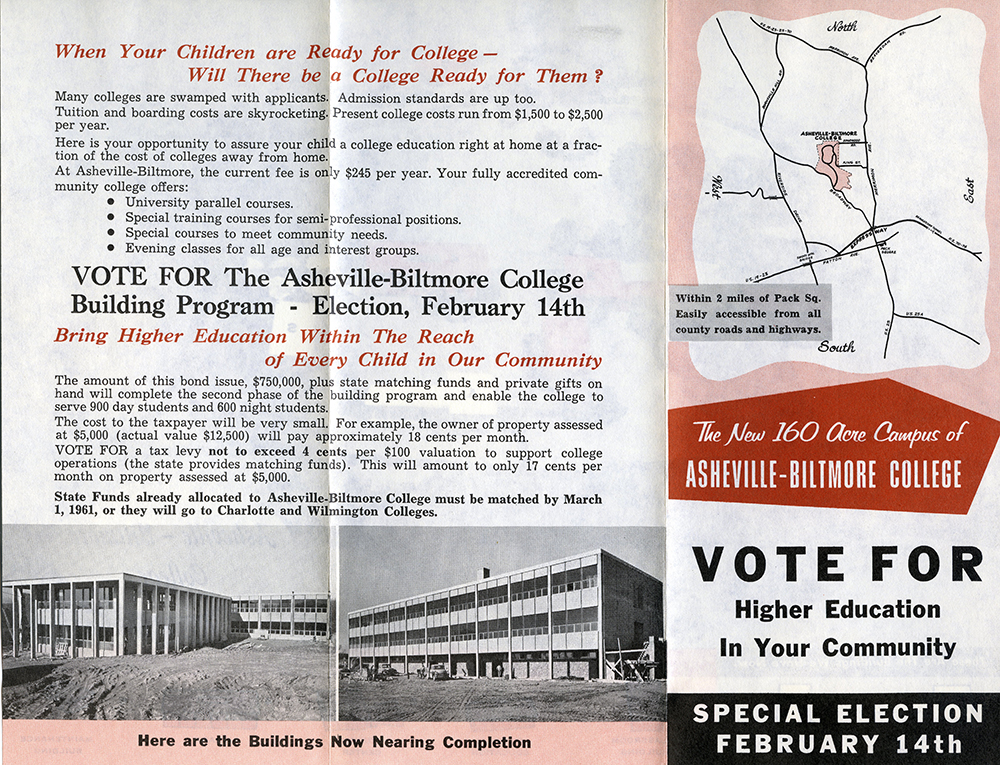

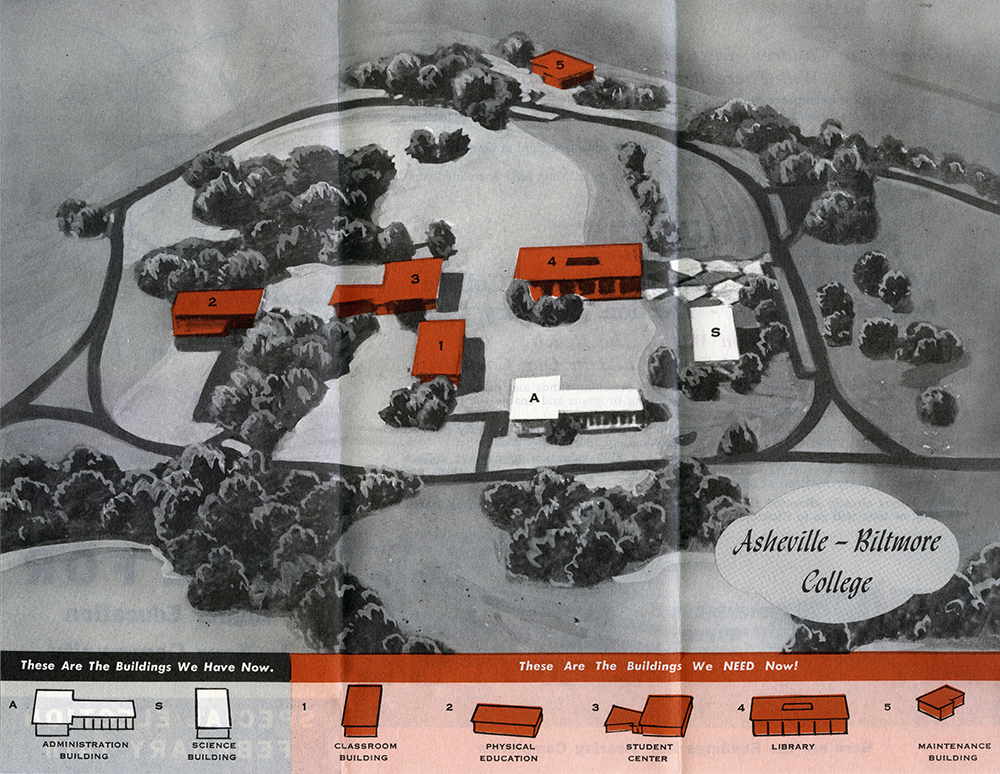

Building “a maintenance building, physical education building, [which was about to be doubled in size], a student center, a library, a building for the humanities, and a dormitory village”.

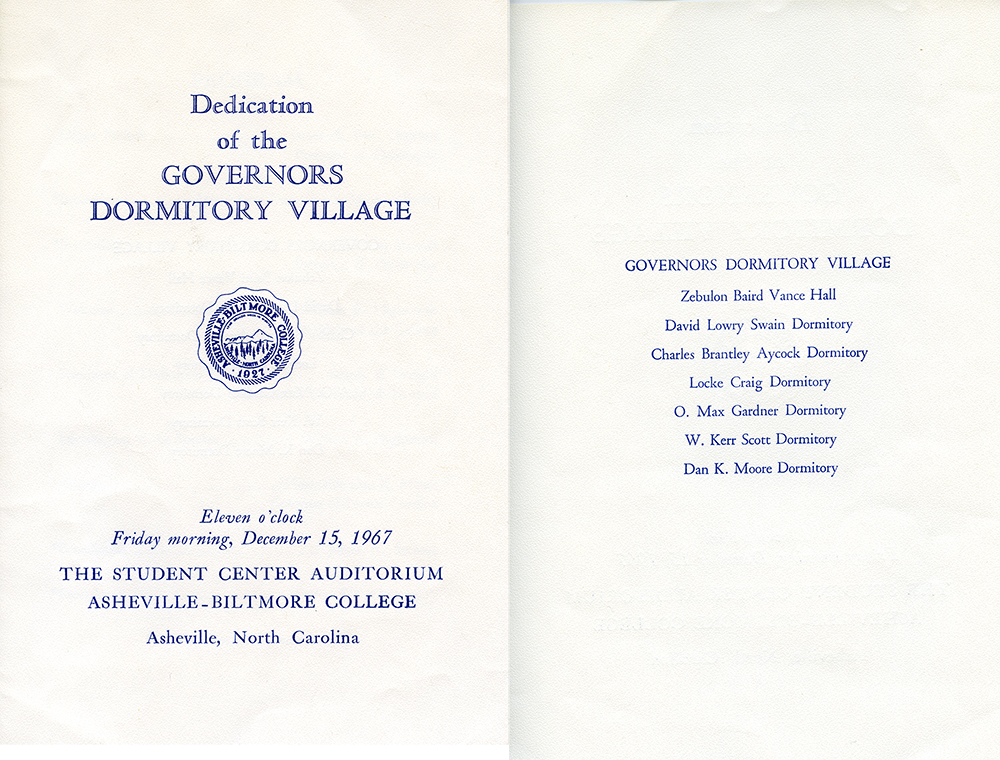

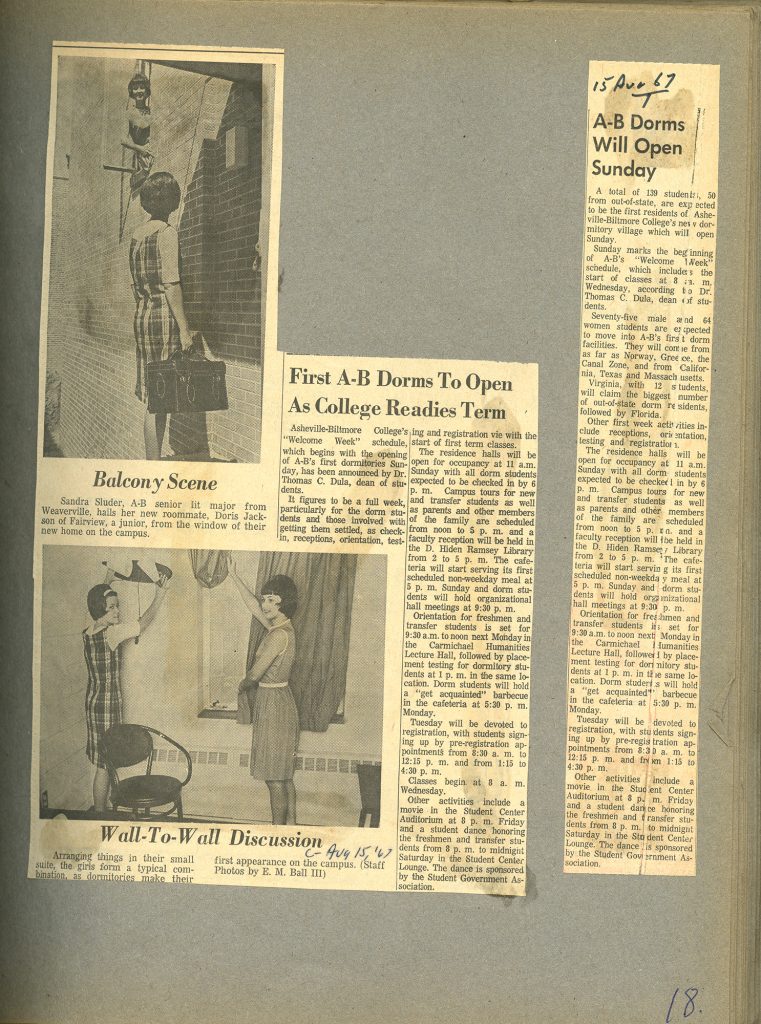

The “village” was Governors Dormitory Village which opened in August 1967 with seven buildings, each named for a governor who was either from Western North Carolina, or advanced higher education in the state.

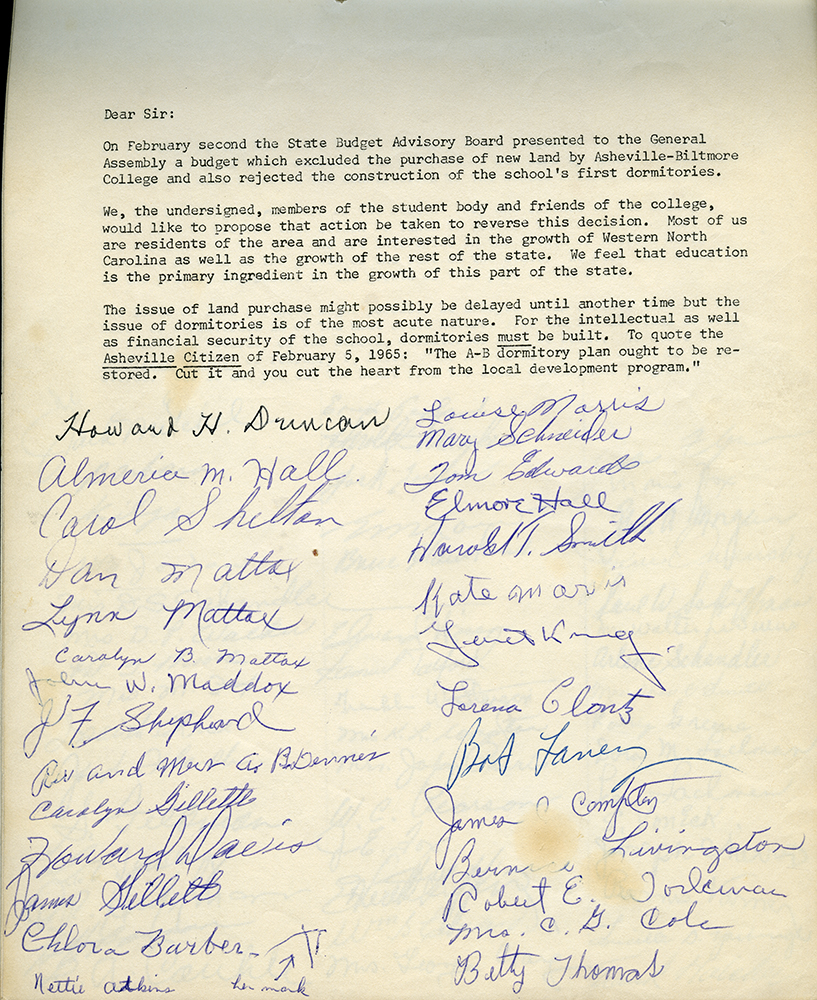

But it was not just the students. In his President’s Report for 1963-4, Highsmith wrote that the college had a program to “move us into the front rank of liberal arts colleges of this area”. He went on to say that this would not happen if it served only the students of “a restricted and low population area”, and dorms “would not be aimed at eliminating local students but….provide a far richer experience for all students.”

Of the seven buildings in the dormitory village, three were men’s halls, three, women’s halls, and one, served as Social Center and also housed a dispensary. Circa 1968, room rent was $85 per 10-week term, plus a $5 health fee, and a $7 linen fee. Draperies and a linen service were provided but “necessities”, to be provided by students, included blankets, hand towels, pillow, wash cloths, laundry bag and bedspread, the latter “preferably purchased after [the student was] in residence”. A typewriter, radio, record player, iron, shoe rack, alarm clock, ash trays, metal waste basket, and rug (2 x 4 washable) were all identified as “optional”.

The rules for drinking alcohol in the dorms seem to have been different for each gender. An undated list of regulations for the men’s dorms listed six typed rules and two added in pencil. These restricted open carry outside dorms, drinking in the suite living room, and included a responsibility to keep the grounds clean, with possible suspension of drinking rights for infractions of the rules.

Meanwhile, in May 1968, the women’s dorms held a secret ballot to see if beer and wine should be allowed in the dormitories at all. Thirty-three voted in favor, with twenty-two opposed, but the rules proposed for the women were much stringent than those imposed on the men. For example, women under the age of twenty-one were to get their parent’s permission to drink (the minimum legal age to drink was eighteen then), and when the student was “transporting her purchase from the parking lot to her dormitory, she must use the proper receptacle provided by the grocery store so that her purchase is at all times concealed and known only to herself.” Furtiveness was also inferred by other rules mandating that beer cans and/or wine bottles only be disposed of in the trash cans “at the bottom of the stairs in each dormitory,” and beer cans and/or wine bottles “could not be stored on the window sills in individual bedrooms”.

It needs to be stated that the proposed rules were drawn up by the women themselves, and in presenting the ballot results and proposed rules to the Dean of Women, the (female) Chairman of the Inter-Dormitory Council showed, what could be described as, lukewarm enthusiasm for allowing alcohol; her memo identifying that those opposed were “unquestionably a proportionately large percentage”, and questioning if the women would obey any regulations anyway as, “the very few rules we have at the present time are, in many in instances, neither heeded nor enforced.”

Visiting hours were also different for the sexes. Although men and women could have visitors Friday evening until curfew, and also during set hours on Saturday and Sunday, the men were allowed additional visiting hours between 7pm and 10pm on Wednesdays. Why these extra hours were needed is not recorded.

There is however a record of a request from Moore dorm, that they be allowed the basement of Scott dorm for a rec room. This would then allow the basement suite the basement of Moore to be used “for boys to wait on their dates.”

No other dorms appear have made a similar request.

In 2011, the remaining five halls in Governors Village were renovated and, along with five other residence halls, they still provide accommodation for UNC Asheville students.

- Colin Reeve, Special Collections