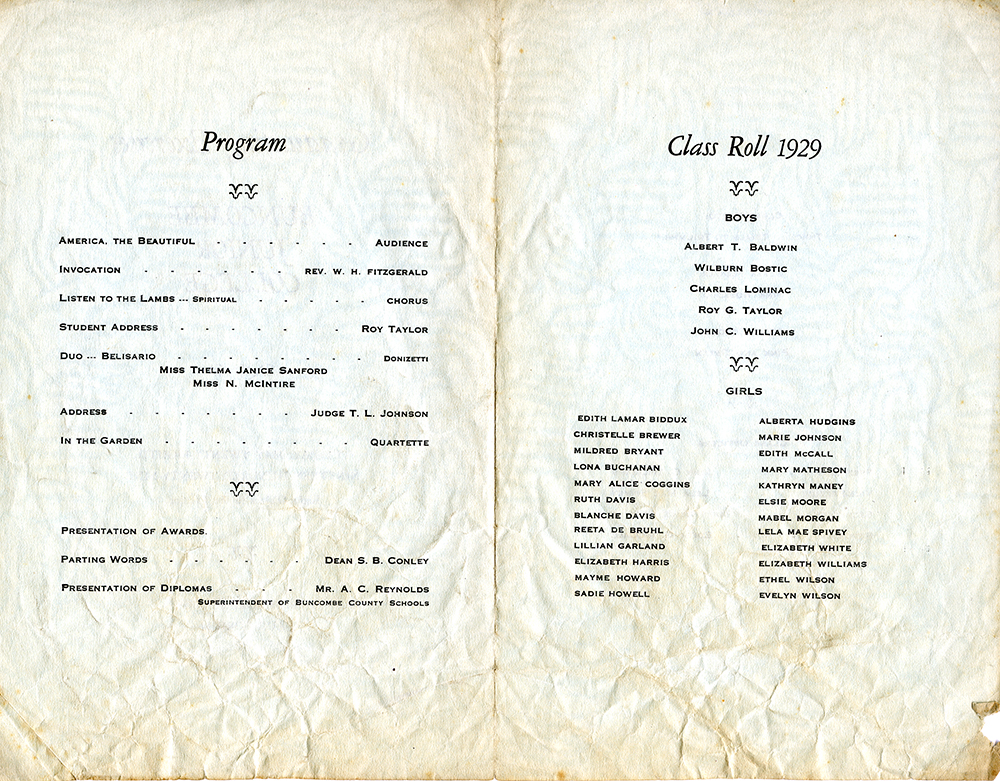

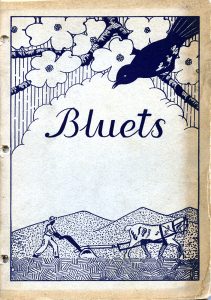

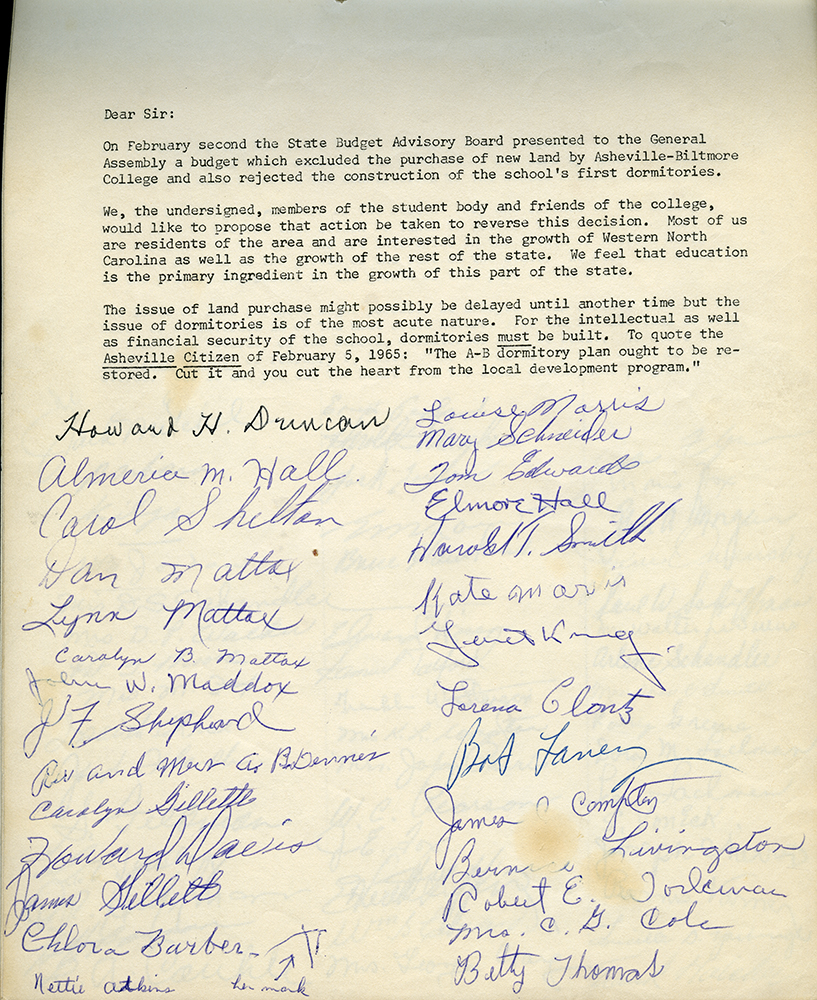

It is not known exactly when the first student newspaper was published by the predecessors of UNC Asheville. In his speech to the Class of 1929, Roy Taylor mentioned a school paper, so clearly publication started within two years of the creation of Buncombe County Junior College.

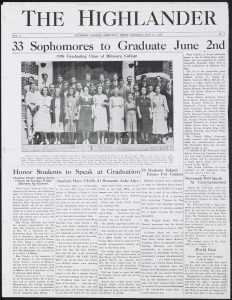

The earliest edition in the University Archives is a photocopy of the May 1930 edition of The Highlander, which was, “Published by the students of Buncombe County Junior College [and] founded by the Class of ’29.” This edition is identified as Vol. II No. 8, suggesting a monthly publication, with Vol 1 No. 1 appearing sometime during the 1928/29 academic year, which would align with Taylor’s remarks.

The first original newspaper in the Archives is The Highlander dated May 1935, which is confusingly identified as Vol. 1 No.2. Since, Vol.1 nos. 3 and 4 are also in the Archives, and are respectively dated March 1935, and April 1935, the paper still seems to be a monthly publication, but the reason for reverting to Vol. 1, or even if a paper was published between 1930 and 1935, is not known.

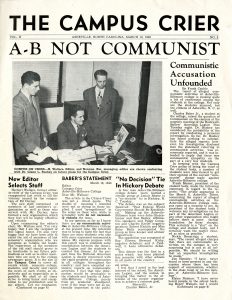

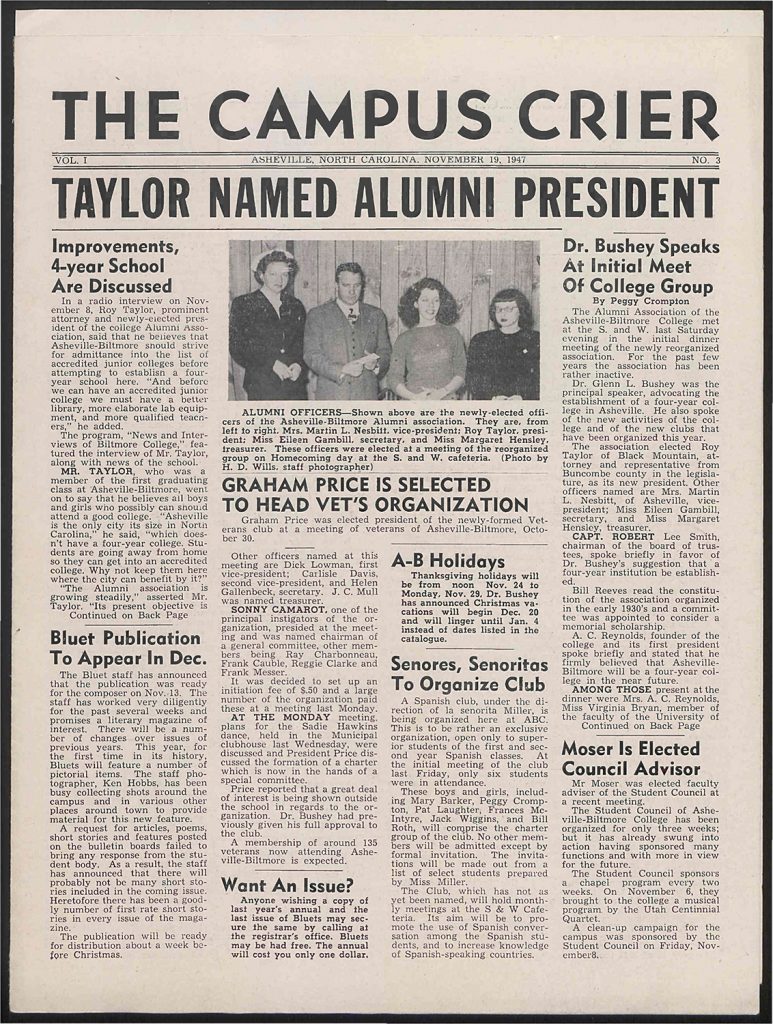

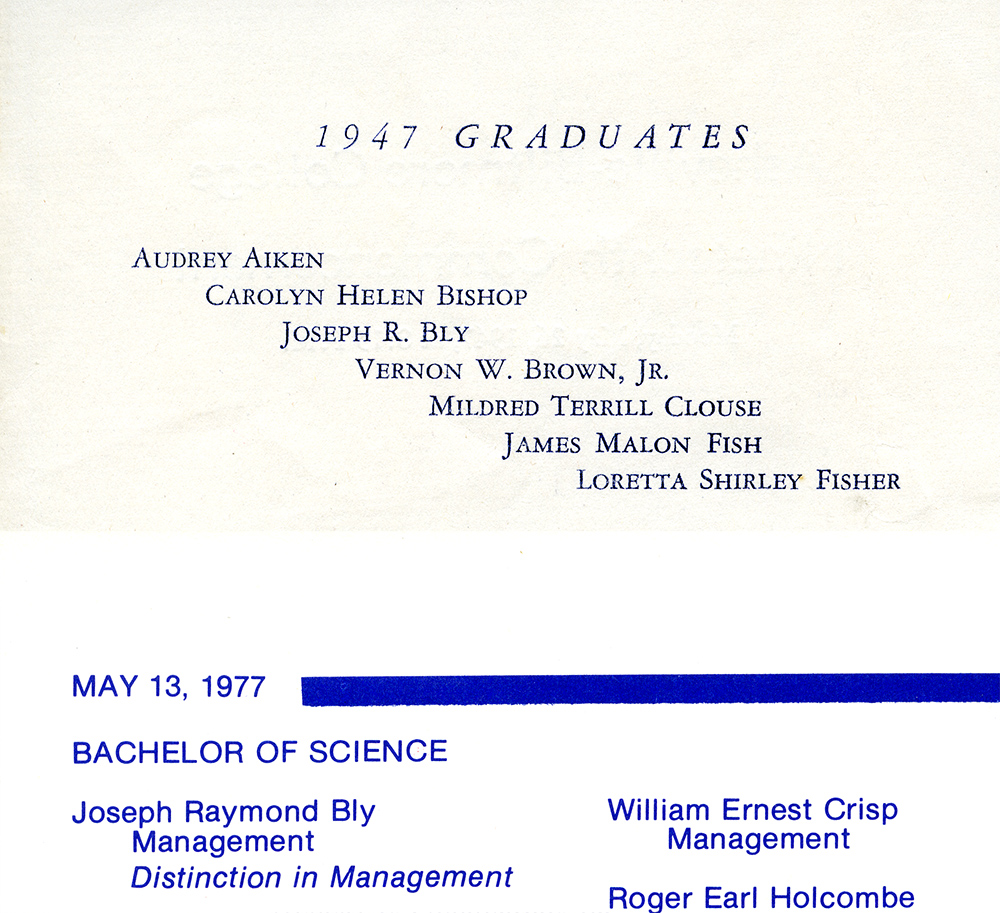

There is no record who won the naming contest, but the newspaper was called The Campus Crier by November 1, 1947 when Vol. 1 No.2 was issued.

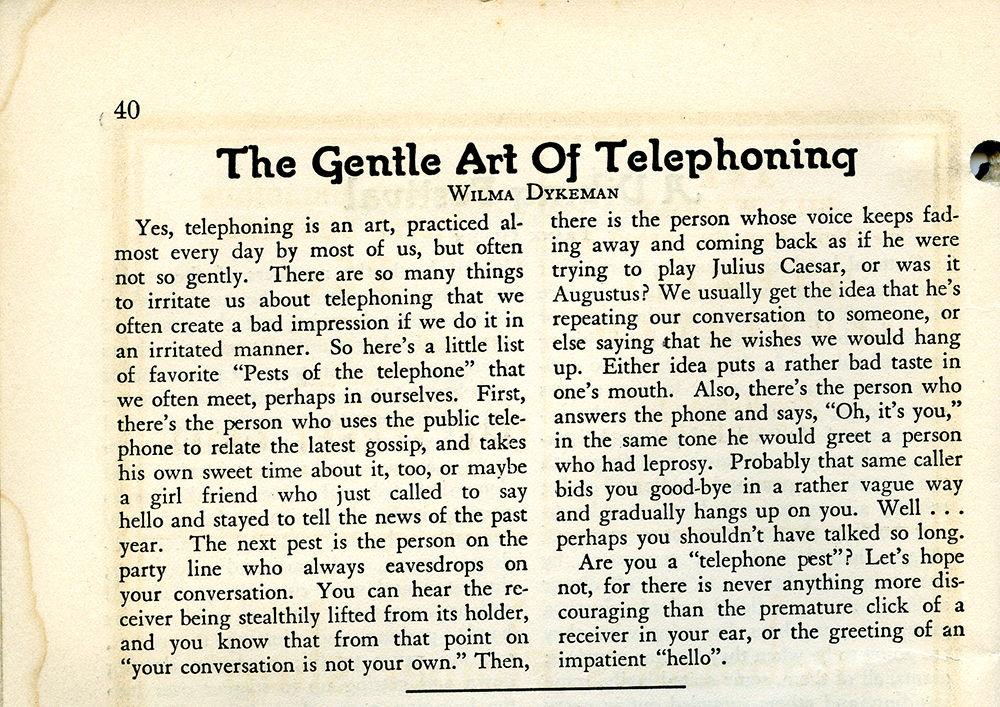

Throughout its run however, The Campus Crier was still internally focused with college news, editorials, and letters, supplemented by the local business advertisements.

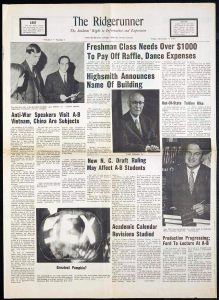

Chronologically, the next newspaper in the Archives is Vol. 1 No.1 of The Ridgerunner, dated September 27, 1965. Again, it is unclear if this four year gap is due to missing copies, or because no paper was published.

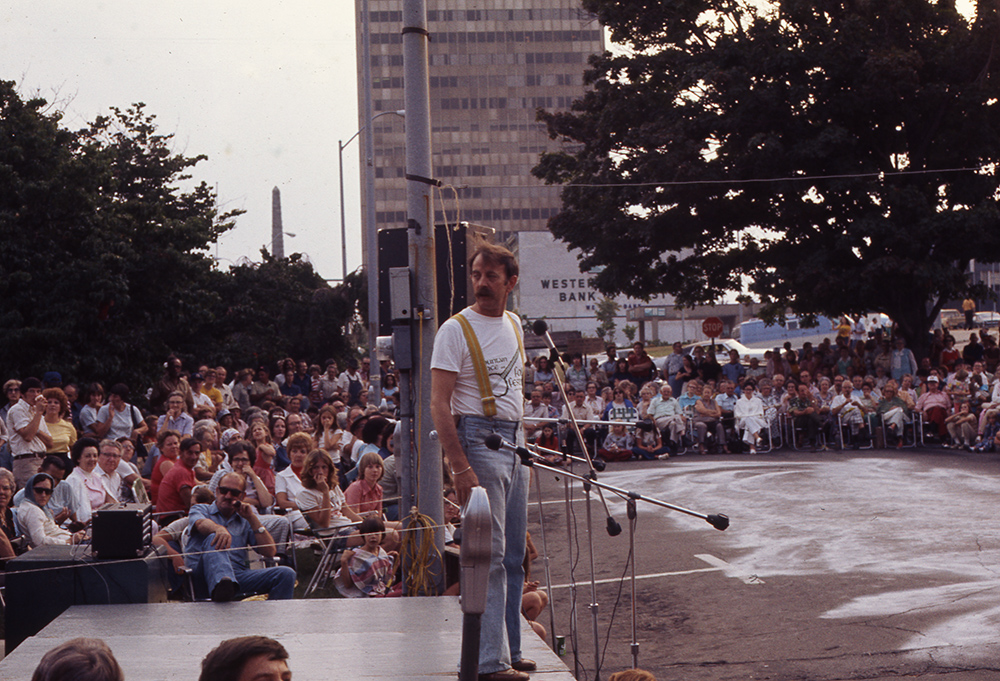

Unlike The Campus Crier, The Ridgerunner was published by the student union, but initially it still followed the same college focused editorial style of its predecessor. However, the content soon expanded to include local and national news, record and movie reviews, and political commentary.

The last Ridgerunner in the Archives is dated February 2, 1979. Again it is unclear is this was the last issue or just the last one archived, but on February 28, 1979, Vol. 1 No. 1 of The Rag & Bone Shop was published.

This was much more of a literary paper than a newspaper, with early issues having an address c/o The Ridgerunner, as though, initially at least, it was meant to supplement, rather than replace, The Ridgerunner. By the fall of 1979, the content had become news than literary but, by 1982, it changed once again, becoming much more a glossy literary journal that was published monthly.

In addition to being unsure of its content, the publication also seemed unsure of its name, with “Shop” disappearing from, and then returning to, the title.

The Rag & Bone Shop ended in controversy. The April 1982 edition featured a drawing of a crucified Easter bunny on the front cover, leading to protests, including the burning and confiscation of the offending issue. The magazine staff claimed first amendment rights, and produced a further edition in May 1982, but with no one willing to be the next editor, The Rag and Bone Shop ceased publication.

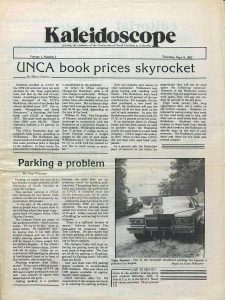

The focus was still campus news and events, supplemented by entertainment reviews and classified advertisements.

The editorial in the first issue explained the name “Kaleidoscope was chosen because it implies something that is constantly changing and showing many different views.” Production of the newspaper was open to any student who wished to participate and it was funded through student fees paid with tuition.

The final Kaleidoscope was Volume IV, Number XIV, dated April 1984. By then, non-campus news formed about half of the items, and there was much greater use of photographs.

The newspaper gave several reasons for the name change. Students said kaleidoscope was “hard to spell,” faculty thought the name “artsy…unprofessional,” administrators wanted a name “that better reflected the campus,” and several Asheville businesses were called Kaleidoscope.

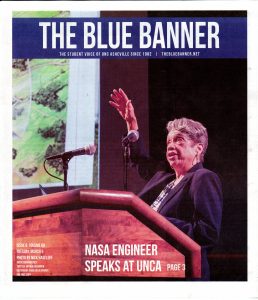

But why The Blue Banner?

Apparently because blue was “one of [the] school colors…and banner is a newspaper name that goes well with blue.”

Irrespective of the reason for the name, it still continues, making The Blue Banner the longest lasting running title of all student newspapers at UNC Asheville and its predecessors.

Throughout its existence, the quality of journalism featured in The Blue Banner has been frequently recognized and praised. The most recent example being in February 2017, when the newspaper earned six awards at the N.C. College Media Association’s conference.

Colin Reeve, Special Collections

Footnotes:

- The above is a brief summary of “official” student newspapers. “Unofficial” publications have included The Scholastic Screamer and the UNC-A Free Press, whilst publications such as The Paper and Bulldog Barker were published by university administration rather than the student body.

- Digitized copies of most archived newspapers through to 2015 are available online at DigitalNC

- The University Archives would like copies of editions of university newspapers that are not currently in the Archives. Please contact speccoll@unca.edu if you have a “missing” edition

![1930 Graduates, Buncombe County Junior College [ABP_3]](http://libjournals.unca.edu/specialcollections/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/ABP_3-1024x810.jpg)

![Gordon Greenwood Clippings Book, (1929-193) [UA11.1]](http://libjournals.unca.edu/specialcollections/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/greenwood002-300x216.jpg)