120 years ago this Saturday, Lucy Saunders (Herring) was born in Union, South Carolina, on October 24, 1900. A pioneering African American educator, she worked as a teacher, reading specialist, and as an educational and community leader from 1916 until 1968. Her work helped transform African American education in North Carolina, especially in Western North Carolina (Krause, p. 188). Her archival legacy includes the Lucy Herring Collection, her memoir Strangers No More: memoirs by Lucy S. Herring, and the Heritage of Black Highlanders Collection, all held in Special Collections at UNC Asheville. Transcriptions of oral histories with Lucy Herring have recently been added to the Special Collections website: July 26, 1977, August 2, 1977 (tape 1), and August 2, 1977 (tape 2).

Saunders’ family moved to Asheville for her brother’s health in 1914. Two years later, when she was 16, Saunders was teaching at the Lower Swannanoa Colored School. A one-room schoolhouse with unpainted walls, a pot-bellied stove, and homemade desks, Lower Swannanoa was one of twelve “colored” schools in Buncombe County at the time. Saunders’ supervisor was John Henry Michael, who was not only the principal of Hill Elementary School, but also the Jeanes Fund supervisor of “Colored Schools” for the county. It was these two factors – the mentorship of John Henry Michael and the Jeanes Fund – that would shape Saunders’ early career as an educator.

Michael conducted the state-accredited Asheville Summer School for Negro Teachers which provided African American teachers with the opportunity to earn and upgrade their teaching certificates, as well as earn credit toward undergraduate college degrees. An experienced educator, Michael was impressed with Saunders’ classroom skills and in 1920 offered her a job teaching third and fifth grades at Hill Street Elementary School in Asheville. Saunders’ talents caught the notice of Annie Wealthy Holland, the North Carolina superintendent of Negro school, and in 1923 Saunders was appointed as a Jeanes Fund supervisor in Harnett County, in the central part of North Carolina.

The Anna T. Jeanes Foundation, also known as the Negro Rural School Fund, or Jeanes Fund, was established by a Pennsylvania Quaker specifically to help maintain and assist rural and country schools for “Southern Negroes.” Originally started with a donation to the Hampton and Tuskegee Institutes in 2005 to assist black schools, by 1909 there were 65 Jeanes supervisors working in 10 states.

When Saunders arrived in Harnett County in 1924, her duties as a Jeanes supervisor were, broadly speaking, to improve education in the county’s black schools, which manifested itself in many ways. She visited all the black schools in the county on a regular basis, encouraged local teachers to teach such topics as sanitation, basic homemaking and light industrial skills. She also encouraged teachers to paint and whitewash houses, develop home and school gardens, as well as other tasks based on the Hampton/Tuskegee model of industrial education and homemaking (Krause, p. 198).

Saunders thrived as a Jeanes supervisor in Harnett County. In the 1920s many black teachers had substandard or provisional teaching certificates. To address this Saunders instituted training programs and extension classes drawing on faculty from nearby Fayetteville State Teachers’ College. Her efforts were part of a larger effort in North Carolina in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1926, only 33% (or 1,917 teachers) of North Carolina’s black teachers had high school educations. By 1928-29 that had dropped to 20%, and a decade later it was down to just 175 teachers. Her role in Harnett County was, essentially, as a county supervisor to the African American schools, raising funds, supervising schools, recruiting and hiring teachers, organizing training, and helping teachers improve their classroom teaching, as well as other administrative tasks.

Saunders also met Asa Herring while working in Harnett County, marrying him in 1925 and giving birth to their son, Asa Jr., in October 1926. Lucy Saunders Herring continued to work in Harnett County until 1935. By that time her marriage had failed, so she moved back to Asheville as a single mother, taking a job teaching English and mathematics at Stephens-Lee High School. Herring would continue working as a Jeanes supervisor in Buncombe County, taking a part-time position as Jeanes supervisor for the elementary schools.

For Herring, moving to Asheville meant leaving the flat North Carolina coastal plain of Harnett County and returning to the mountains. As she said in an oral history in 1977, “I thought and still think from the standpoint of physical beauty, Asheville is one of the most beautiful places I’ve seen…There is something about the mountains that is satisfying and soothing” (Herring, July 1977 oral history).

By the time Herring arrived back in Asheville, the duties of Jeanes supervisors had expanded to also include improving “the quality of instruction,” to conduct meetings on reading and study, to guide field work and extension courses, to help implement standards, to encourage summer schools, libraries, and conferences, and to engage the community. As a Jeanes supervisor Herring became an active leader in Asheville, working with parent-teacher groups and community organizations and raising funds to buy additional books and other materials for schools.

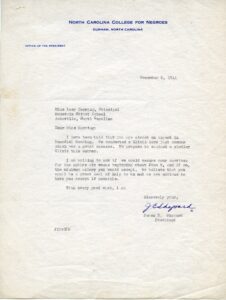

In 1941 Herring was named principal of Mountain Street Elementary School, and by the late 1940s she became the first African American on the Asheville school and supervisory staff to have an office in city hall. At this time she began graduate work at the University of Chicago, traveling there over the summer for three years. She worked with Dr. William Scott Gray, the leading expert on remedial reading who had developed the “Dick and Jane” reading. Remedial reading was one of Herring’s passions, and based on her work with Gray she developed her own reading programs for teachers, supervisors, librarians, and principals. She was seen as an expert on remedial reading in North Carolina, and was invited to teach summer sessions at the North Carolina College for Negroes (now NC Central University) in Durham.

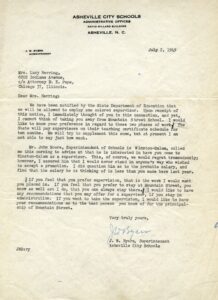

In 1949, the state allowed Asheville to “employ one colored supervisor” in the school system, and Lucy Herring was appointed as the supervisor for the African American city schools in Asheville, a position she held until her retirement in 1964. Herring was also offered a similar position in Winston-Salem but chose to stay in Asheville. During this time she was also president of the North Carolina branch of the National Association of Jeanes Supervisors. She was gaining a national reputation as an effective reading educator and supervisor, and was offered a job at the Tuskegee Institute, which she declined.

Asheville honored Herring in 1961 when the Asheville City Board of Education unanimously voted to name a new school after Herring – the Lucy S. Herring Elementary School, which operated from 1961-67 when it was then closed as part of court-ordered integration.

Herring retired from the Asheville City Schools in 1964, having spent a career exclusively teaching in segregated schools. She remained extremely active in the community after retirement, serving on numerous boards and working to collect materials that document the Heritage of Black Highlanders in Western North Carolina. The materials she and others gathered constituted the Heritage of Black Highlanders Collection at UNC Asheville.

In 1968, Herring moved to Phoenix, Arizona, to live with her son Asa’s family. Her son, Lieutenant Colonel Asa D. Herring, Jr. was a fighter pilot and wing officer in the Air Force, and served in Vietnam when Lucy Herring was living in Phoenix. He started his career training as a Tuskegee Airman in 1944, but World War II ended before his training was completed. He left the military in 1946, but reenlisted in 1949 after President Truman issued Executive Order 9981 ending racial segregation in the military. Asa Herring Jr. became a fighter pilot and officer and flew 350 combat missions in Vietnam. The Library of Congress has created an Asa D. Herring, Jr. Collection and oral history with Lt. Col. Herring as part of its Veterans History Project.

Lucy Herring published her memoir, Strangers No More: memoirs by Lucy S. Herring, in 1983. She lived the rest of her life in Arizona, and passed away in Phoenix in October, 1995, a few days before her 95th birthday.

Sources:

Heritage of Black Highlanders Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville 28804. Digitized by Digital NC.

Herring, Lucy S. Strangers No More: memoirs by Lucy S. Herring. New York: Carlton Press, 1983.

Herring, Lucy S. Interviews with Louis Silveri. 1977. Transcripts. Southern Highlands Research Center Oral History Collection. D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville 28804.

Krause, Bonnie J.,“‘We Did Move Mountains!’ Lucy Saunders Herring, North Carolina Jeanes Supervisor and African American Educator, 1916-1968,” The North Carolina Historical Review 80, no.2 (April 2003): 188-212.

Lucy S. Herring Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville 28804.