On September 27, 1919, 100 years ago today, The Asheville Citizen ran an ad on page 10 which read:

SANATORIUM

Dunnwhyce Sanatorium, Black Mountain, N.C., reopened under new management, can accomodate ten more convalescents; ideal location; modern and complete.

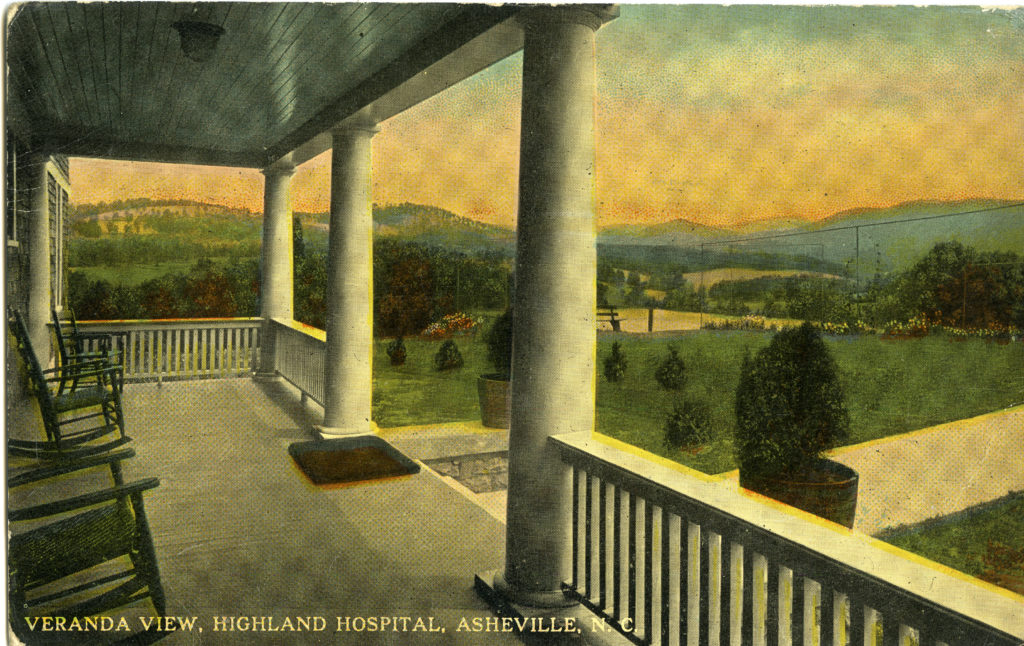

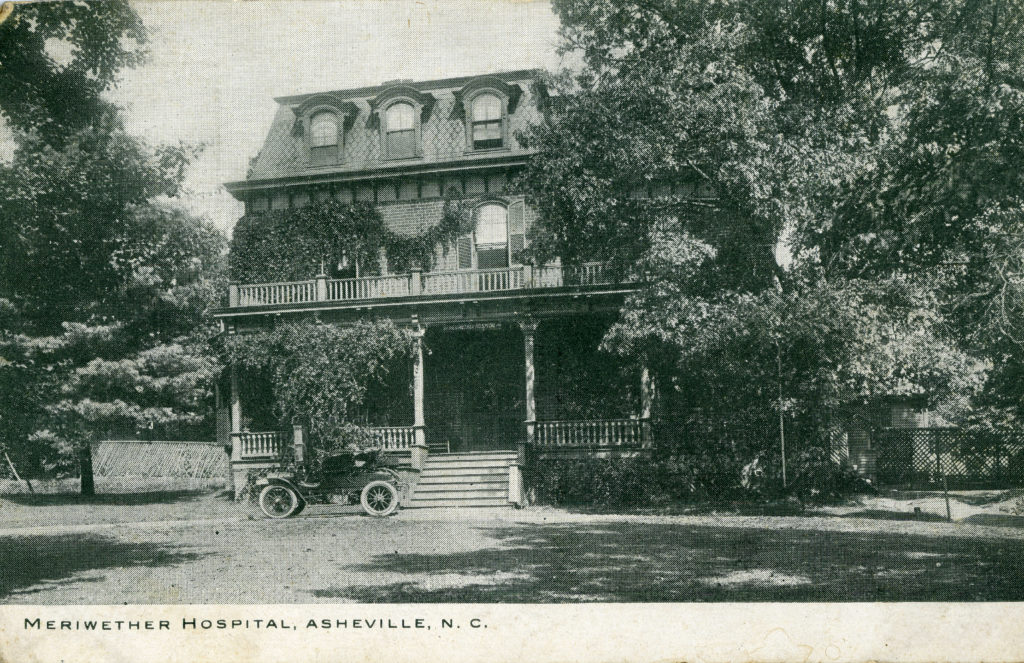

Sanatoria had become a health craze by the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and Asheville had become a mecca for those suffering from tuberculosis. The climate, which was the basis of treatment in these sanitoria, was considered ideal in Western North Carolina. Indeed, for those studying climatotheraphy, Asheville was considered one of the top climates in the treatment of various lung diseases.

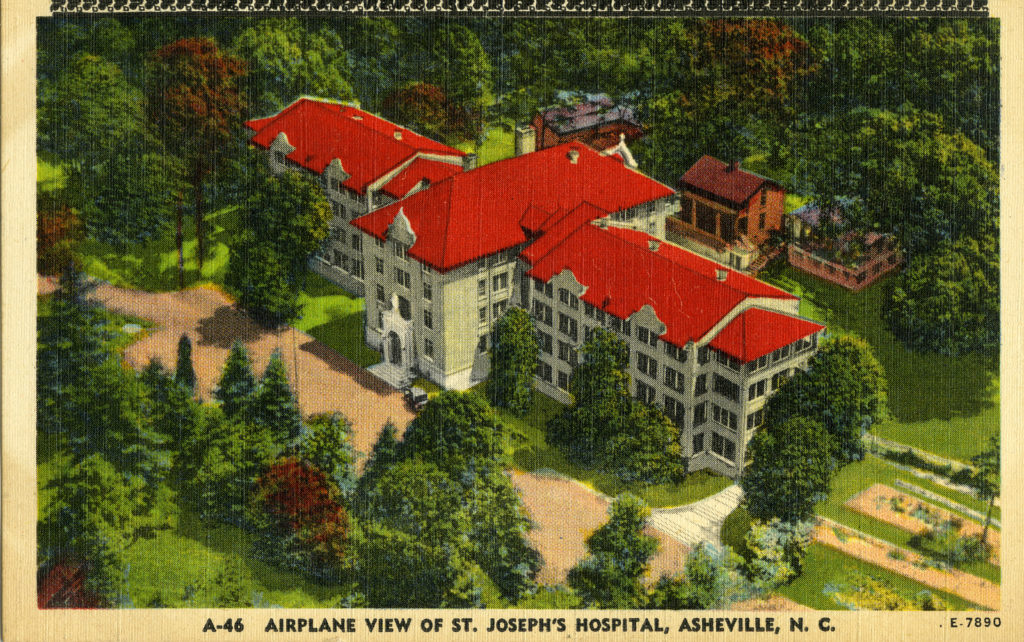

People had long believed, from the low-country elite to the Cherokee Indians, that Asheville fell within the realm of a health resort and by the 1890s, the city and surrounding areas were firmly entrenched in the building explosion of sanitoria. The largest of which was St. Joseph’s Hospital and the Fairview Sanatorium.

The Asheville Citizen ad mentioning “Dunnwhyce,” was actually referencing the sanatorium in Black Mountain, Dunnwyche, a sanitorium for consumptive nurses. During this time period, it was quite common for nurses caring for tuberculosis to contract the disease themselves, and most were single women with limited means for their own healthcare.

During the 1911 annual meeting of the North Carolina State Nurses Association (the professional nursing organization for white nurses in the state), two nurses came forward with the idea of a sanatorium for sick and disabled nurses. Supported by the NCSNA, it would be a place nurses could find care and respite. A site was found in Buncombe County, near present-day Black Mountain, and the new institution was named Dunnwyche, in honor of the two women who first championed the idea, Birdie Dunn and Mary Whyche.

Dunnwyche thrived until 1919, when World War I made it necessary for the US Army to build a 1,500 bed sanatorium at nearby Oteen to care for soldiers with lung ailments related to poison gases used as weapons on the battlefield. The Army’s pay scale was higher than Dunnwyche, effectively removing the majority of those caring for their fellow nurses and patients, and leading to the declining maintenance and financial instability of the sanatorium. The building was sold and the proceeds invested in Liberty Bonds, although the interest was then used to help those nurses who had acquired the disease with finding care and money for treatment costs.

The sanatoria movement in Western North Carolina would go on to become yet another pillar that firmly established Asheville as both a health resort and tourist destination across the globe. Today though, all that remains of much of the history of the sanatoria of this area are simply a memory.

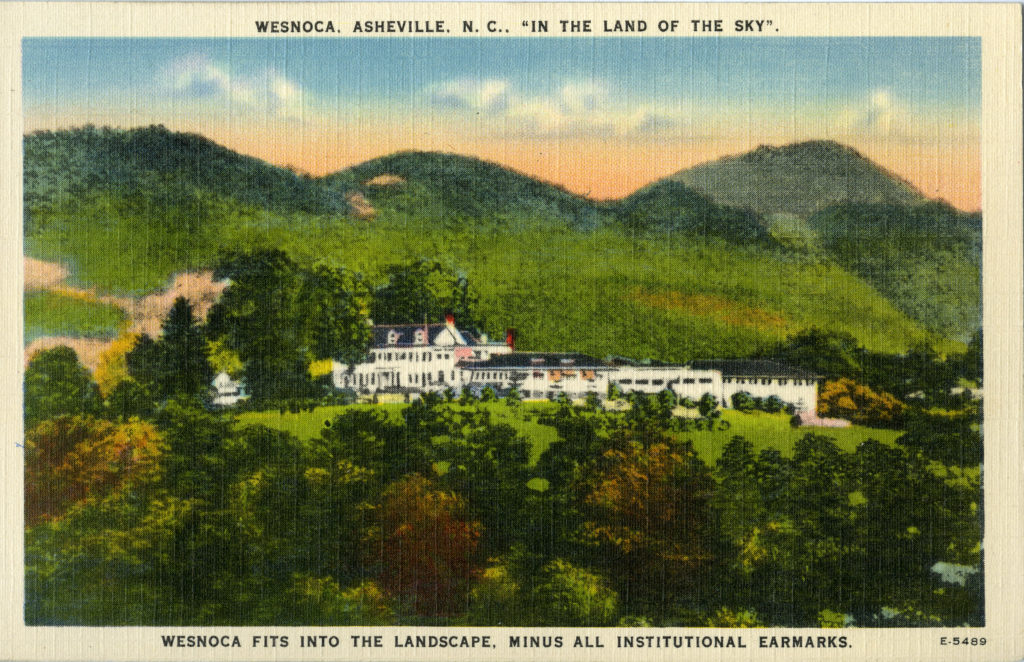

However, at UNC Asheville Special Collections, we are the repository for the Fred Kahn Asheville Postcard Collection. Housed within this postcard collection is a magnificent binder which includes 108 postcards of several of the sanatoria in Asheville and Western North Carolina. Fortunately, through vibrant collections such as the Fred Kahn Asheville Postcard Collection, the legacy that helped shape Asheville into the renowned destination it has become today will remain alive and well for future generations.

Sources:

Buncombe County, North Carolina Nursing History, Appalachian State University, accessed: https://nursinghistory.appstate.edu/counties/buncombe-county

Fred Kahn Asheville Postcard Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina Asheville, 28804.

“Sanatorium: Dunnwhyce.” The Asheville Citizen, September 27, 1919.