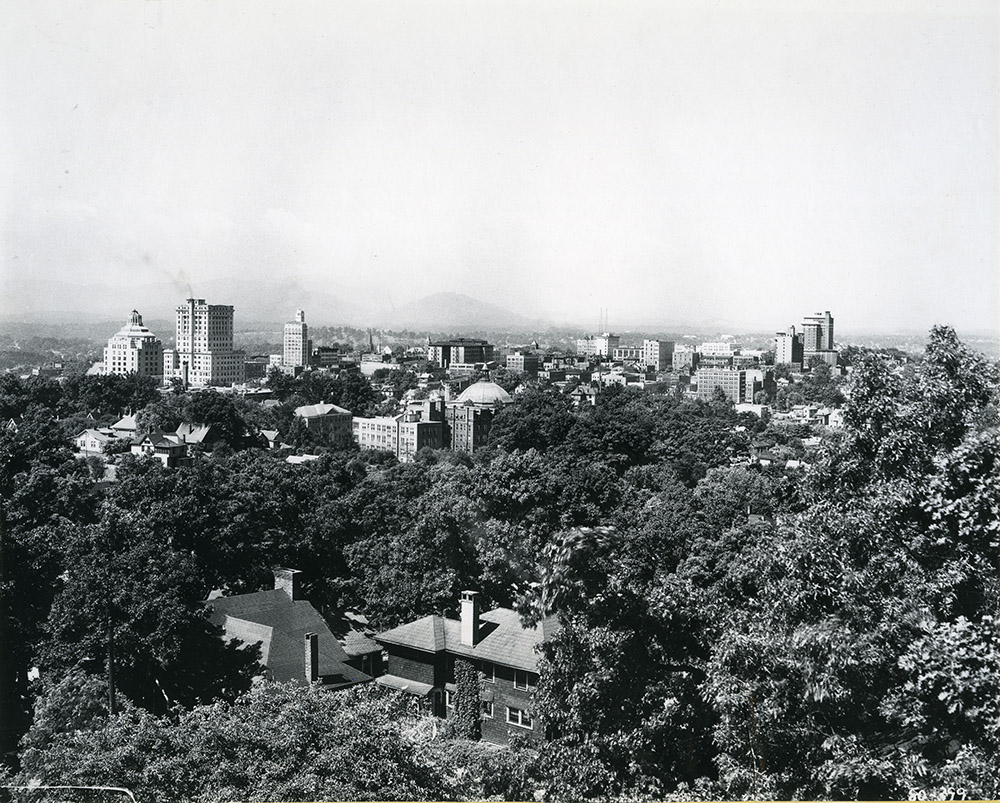

The summit of Beaucatcher Mountain has long provided a scenic vantage point from which to view Asheville, but Beaucatcher also provided a natural obstacle to travel. A solution to the travel problem arrived in 1929, when a road tunnel through the mountain was completed.

However, within thirty years or so, road traffic had increased so much that an additional route through Beaucatcher was starting to be discussed.

And so began one of the most contentious and convoluted road developments in Asheville’s history.

A 1961 master plan recommended remodeling the existing tunnel, and cutting a new second tunnel parallel to the original. Initially this plan was supported by both the city and the state (King 1975), but in 1967, the State Department of Highways recommended a cut instead of a tunnel. Although the cut would be 780 feet wide at the top, 200 feet deep, and 210 feet wide at the base, and remove twenty times more rock than a tunnel (Neufeld 2009), it would cost less money.

The cut was supported by the United States Bureau of Public Roads. (The new road was being built using matching Federal Funds). But in 1970, the Bureau reversed its position and favored a tunnel, citing environmental and highway needs, and design work began on a new tunnel (King 1975). Two years later in 1972, and based on a new estimate that tunneling would cost $17M against $10M for an open cut (King 1975), and the 1969 National Environmental Policy Act (Neufeld 2009), the Federal Government again changed its view and gave approval for the open cut.

Local opposition to the cut coalesced as the Beaucatcher Mountain Defense Association, and in 1975 the Association filed suit in Federal Court to stop the cut. An injunction was denied and construction work began. Lined up against the defense association were the city, state, and Federal governments, the local Chamber of Commerce, and the newspapers, who all favored the cut on the ground it was cheaper and faster to build (King 1975).

The Defense Association returned to court in 1976, this time arguing the cut would damage historic sites, including Zealandia, the historic mansion located 500 feet from the edge of the cut (Neufeld 2009). The injunction was again denied, and in 1977, blasting began.

The cut, and the road through it, were completed in 1980, but completion did not diminish opposition.

Writing in 2012, local author Charles Frazier referred to “the 240 Bypass with its still-horrifying cut through Beaucatcher Mountain” (Frazier 2012).

Betty Lawrence, one of the people who led the Defense Association said the cut lost “some of the real magic of Asheville”, and “that Asheville was a city surrounded by mountains, and now it’s a city surrounded by mountains with one great big gash.” (Hunt 2017).

With plans being developed for the I-26 Connector through Asheville, road layouts are likely to once again become a hot topic of local contention and conversation.

Colin Reeve, Special Collections

Sources:

Frazier, Charles. “Random Asheville Memories circa Mid-Twentieth Century.” In 27 Views of Asheville: A Southern Mountain Town in Prose & Poetry, with an Introduction by Rob Neufeld, 32. Hillsborough, NC: Eno Publishers, 2012.

Hunt, Max. How intersate highways changed the face of WNC. March 10, 2017. https://mountainx.com/news/how-interstate-highways-changed-the-face-of-wnc/ (accessed October 30, 2018).

King, Wayne. New York Times, December 1, 1975.

Neufeld, Rob. The Read on WNC. March 29, 2009. http://thereadonwnc.ning.com/forum/topics/remember-the-cut (accessed October 30, 2018).