This is the second in a series of articles highlighting materials in the Bill and Alice Hart Collection, which the Harts donated to UNC Asheville’s Special Collections. This article highlights works documenting the Cherokee Nation.

Bill and Alice Hart’s Collection of the history and culture of Western North Carolina includes extensive works on the Cherokees, who have lived in this part of the world longer than any other humans. The Cherokee trace their roots in Western North Carolina to approximately 8000 b.c.e., and controlled about 40,000 square miles of territory in Southern Appalachia prior to the arrival of Europeans. Understanding the relationship of humans to the natural world in Southern Appalachia requires an understanding of Cherokee history and culture, and it is in this context that Bill and Alice Hart built an extensive collection of materials on the Cherokee.

The following is a selection of the Cherokee materials in the Hart Collection.

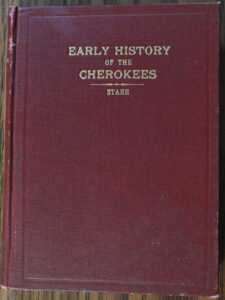

Early History of the Cherokees

Emmet Starr’s Early History of the Cherokees: Embracing Aboriginal Customs, Religion, Laws, Folk Lore, and Civilization, was published in 1917, and considered a landmark historical account of the Cherokee nation. Starr establishes his credentials in the book’s Preface: “I am a Cherokee, born in Going Snake District, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, on December 12, 1870.” Starr spent over 15 years researching this history, and the volume includes extensive use of primary sources. This first edition, self-published by Starr, is relatively rare.

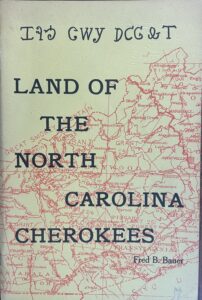

Land of the North Carolina Cherokees

Published in 1970, Fred B. Bauer’s Land of the North Carolina Cherokees is a concise (70 page) history of legal issues concerning the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and their struggles to maintain their constitution and land rights in the Qualla Boundary. Bauer was a former Vice Chief of the Eastern Band, and was an outspoken advocate for Cherokee rights to their land during the development of the Blue Ridge Parkway.

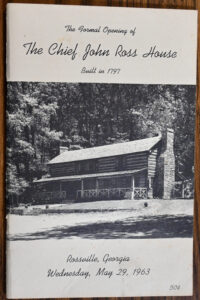

Formal Opening of the Chief John Ross House – offical program

John Ross served in leadership roles for the Cherokee Nation from 1819 to his death in 1866. Ross was President of the Ntional Committee of the Cherokee Nation from 1819 to 1827, the year that the Cherokee Nation adopted its Constitution. In 1827 he was Assitant Principal Chief, and in 1828 was elected Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. He was relected as Principal Chief and held the position until his death in 1866.

The John Ross House in Rossville, Georgia, was built in 1797 by John Ross’s grandfather John McDonald. The house was restored 1963, and this program documents the Formal Opening ceremonies, which included a stick-ball game, archery, crafts, and dancing.

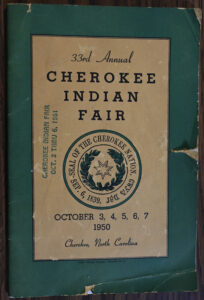

33rd Annual Cherokee Indian Fair program, October 1950

The Cherokee Indian Fair provided members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians an opportunity to exhibit “the products of their fields, forests, and farms, their cook stoves and preserving kettles, their needles and looms, all the best of their wood craft, metal work, and pottery; in fact any products of their minds and hands in which the can take pride.” The program is illed with photographs and details about the wide range of items being exhibited and sold, including fruits, vegetables, canned goods, baked goods, clothing, plants, flowers, and crafts.

Cherokee Fair & Festival: A History thru 1978

This 1978 pamphlet edited by Mary Ulmore Chiltoskey provides more depth and historical information about the Cherokee Indian Fair. It cites 18th century European descriptions of Cherokee harvest festivals in such historical narratives as John Lawson’s History of Carolina and William Bartram’s Travels of William Bartram, then adds contemporary Cherokee accounts of the Fair’s growth and development.

The Hart Collection includes documents and resources about Cherokee law, as well as nineteenth century congressional papers documenting Cherokee attempts to have treaty promises fulfilled. These include the Constitution and Laws of the Cherokee Nation, Published by Authority of the National Council, 1875, and Congressional documents such as the US House of Representatives Bureau of Indian Affairs report “Cherokee Indians in North Carolina” from 1848, the U.S. Senate document “complaints of treaty violations by US, delivered by Cherokee delegation of Will P. Ross, W.S. Coodey, and John Drew, March 15, 1849,” and the U.S. Senate document “Committee on Indian Affairs, report on accounting balance owed the Cherokee nation by the US according to 1846 treaty terms.”

A small but representative sample of other Cherokee resources in the Hart Collection includes Art of the Cherokee : Prehistory to the Present by Susan C. Power, Cherokees of the Old South: a People in Transition by Henry Thompson Malone, The Shadow of Sequoyah: Social Documents of the Cherokees, 1862-1964, Cherokee Legends and the Trail of Tears from the Nineteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Cherokee Cavaliers: Forty Years of Cherokee History as told in the Correspondence of the Ridge-Watie-Boudinot family, as well as numerous issues of the Journal of Cherokee Studies and North Carolina Archaeology.

One of the most important works in the collection is a first edition of The Cherokee Physician, Or Indian Guide to Health, as Given by Richard Foreman, a Cherokee Doctor. Originally published in Asheville in 1849, this book merits its own blog post. We will feature a special guest discussing The Cherokee Physician in a future blog post. Stay tuned!

For more information about these materials, please watch this video of Bill Hart discussing the Cherokee resources in the Hart Collection. This was recorded in the Hart’s private library prior to transferring the collection to UNC Asheville, but we have retained the original order that the Harts used to organize their collection.

The Bill and Alice Hart Collection is open to all, and we encourage you to contact Special Collections to make an appointment to spend time with this marvelous collection. Please contact us at speccoll@unca.edu to make an appointment. We look forward to seeing you soon!

– Gene Hyde and Ashley Whittle