Editor’s note: We were delighted to have Shelby Beard as an intern in Special Collections this semester. Her previous post discussed her research on UNCA’s John Martin’s Book Collection. In this post she explores some books from our Rare Book collection. Shelby, an English Major, graduates this semester.

By Shelby Beard, Special Collections Intern

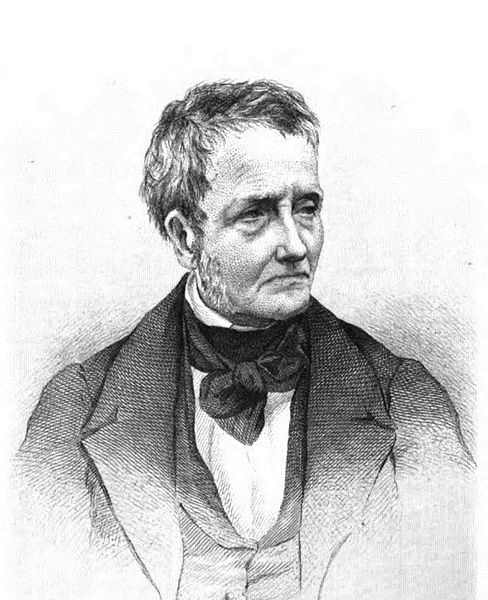

The Confessions of an English Opium-Eater

Thomas de Quincey

Content warning: addiction, drugs

Thomas de Quincey was born in August, 1785, in Manchester, England. From an early age, it was clear that Thomas was creative and saw the world from a unique perspective. After the death of his father and two of his sisters, he was cared for primarily by a handful of legal guardians, which filled his life with conflict and transition. After attending two grammar schools, and fleeing the later, he went to university, and soon developed a relationship with a number of prominent writers at the time, such as William Wordsworth (and his family) and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who proved to be influences in his writing career. Another influence on his career was opium, which de Quincey took for the first time in 1804 in hopes of quelling the pain of his “severe rheumatic pains in his head and jaw” (Agnew 34). At the time, opium was commonly and legally used to treat pain, but many people, including de Quincey, became addicted to the substance after taking it for a short time.

In his autobiography, The Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, de Quincey details the perks and downfalls of opium (or more specifically what was likely laudanum, a mixture of opium and alcohol) addiction and his own experiences with it, including the dreams he had under the influence. De Quincey began writing for Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in 1820, where he would publish Confessions as a two part series that would eventually be published as a book. Confessions was an immediate success and “brought [de Quincey] lasting fame” (Agnew 37). Despite his struggles with addiction, de Quincey maintained his writing career through most of his life. He regularly contributed to Blackwood’s, as well as Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine, and published essays and books independently. Throughout his successful career, de Quincey struggled with money, and he was in and out of debtor’s prison nine times from 1832 to 1840. So despite his success, his family continued to struggle. Near the end of his life, de Quincey’s battles with addiction and debt began to fade. Under the careful watch of his children after his wife’s death, de Quincey paid his debts and lived fairly comfortably until his death in December of 1859.

As previously stated, The Confessions of an English Opium-Eater is an autobiographical account of de Quincey’s experience with opium addiction. Confessions is, as the title implies, a confession piece, which is a form of autobiographical literature that exposes intimate details of the subject’s life. Writing in the Romantic era, de Quincey was pretty much alone in discussing addiction in the context of an English gentleman’s life, rather than a cliché junkie on the streets. He was also alone in discussing both the “pleasures” and the “pains” of opium, rather than outright condemning the substance and anyone who would touch it. De Quincey was famously fond of opium, though as he writes in his revised introduction, he was not proud of his addiction. This book is a compelling story, told in a stylistically unique fashion that helps the subject matter stand out in a crowd.

On ‘Tao Te Ching’

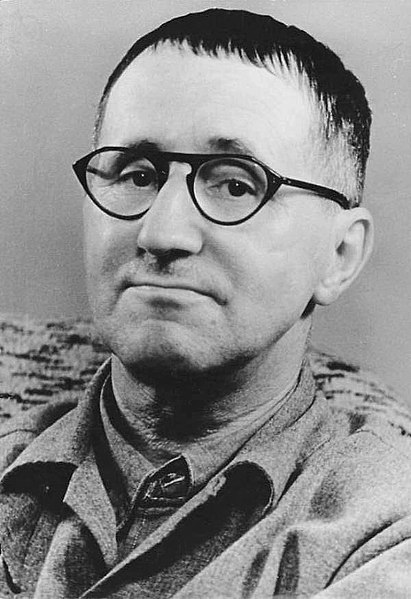

Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht was most well-known for his play writing, but also wrote some poetry and fiction before his death in 1956. He is often remembered for his Marxist views that are apparent in his writing, which has made him a controversial figure amongst literary scholars. Bertolt Brecht’s On ‘Tao Te Ching’ is a short poem about an old man on a journey. This pocket sized book is number 85 of 150 numbered editions printed by Nancy Chambers for the Anvil Press in 1959. It is printed on rice paper, the cover is coated in decorated paper with the title pasted on the binding, and it includes illustrations pulled from a collection of Chinese prints. This is a beautiful book, and as a first (and only) edition could be valued at over $200 dollars. Little is known about this book, which makes it an intriguing addition to the rare books collection in UNCA’s Special Collections.

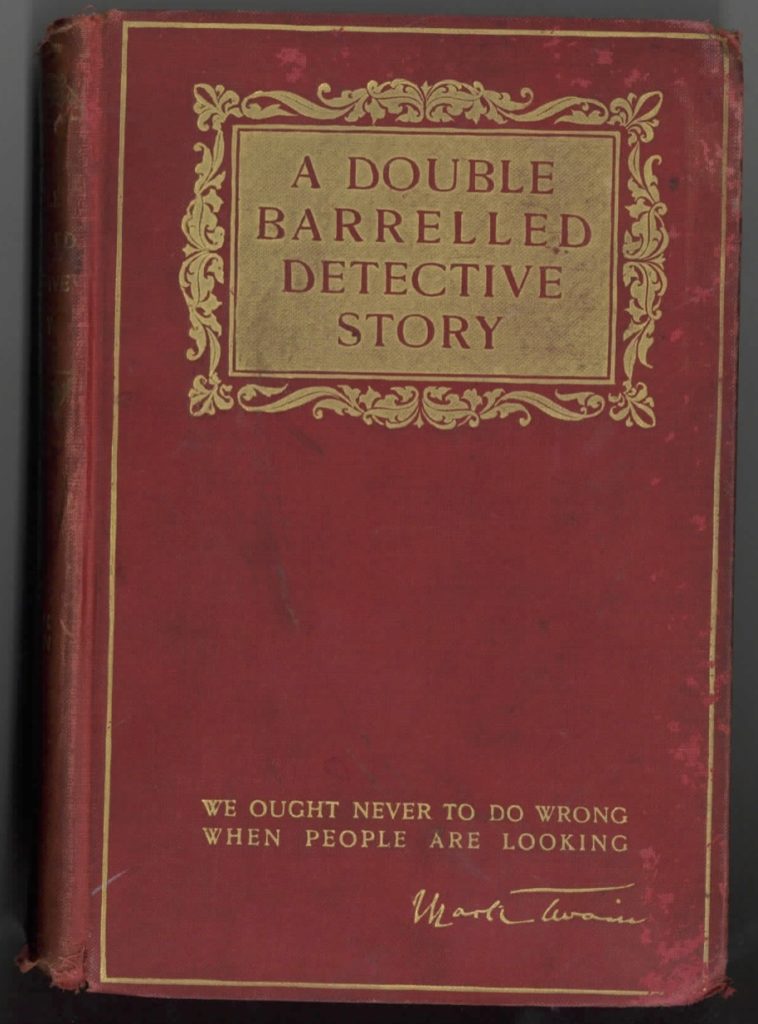

A Double Barrelled Detective Story

Mark Twain

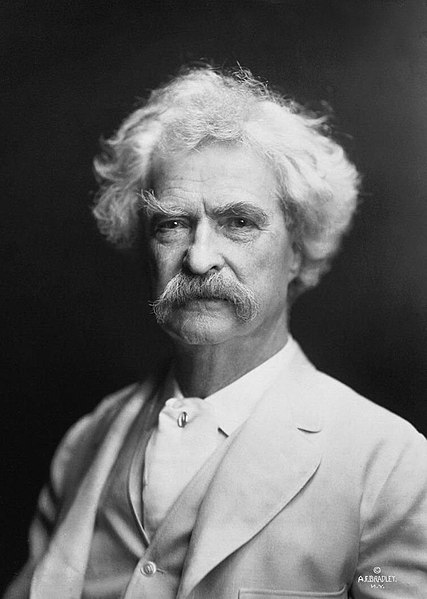

Samuel Clemens was born on November 30, 1835, in Missouri, where he spent most of his childhood years by the Mississippi River. As a young adult, Clemens worked as an apprentice, a compositor, a writer for local newspapers, a journeyman, and a steamboat driver. He eventually adopted the pen name Mark Twain, which is a riverman’s term for “water that is safe, but only just safe, for navigation” (Gale 2). Twain continued to write for newspapers, began venturing into travel correspondence, and eventually began writing and lecturing on various topics. In 1870, Twain married Olivia Langdon, and they moved to Hartford, Connecticut, where they would live for the next twenty years and have their three daughters. Twain also started gaining popularity as a writer and lecturer at this time. Twain’s early work was sold by subscription, and sold well, which granted Twain a sizable profit. However, he soon fell into debt after his publishing company went bankrupt and his typesetting machine failed to make his fortune. He and his family moved to Europe, where they could live cheaper, until Twain was able to pay off his debts and return to the United States in 1900. By this point, Twain was reaching new levels of popularity and considered a public hero to some. He is often thought “among the best to express, or expose, the spirit of the American people” through his writings (Gale 4).

Some of Twain’s most well-known books are The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885) and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1875), which center around quintessentially American notions of life along the Mississippi river, and The Innocents Abroad (1869), which is a humerous retelling of Twain’s travels. A Double Barrelled Detective Story (1902), is different from Twain’s more popular works. He write it later in his career, at a time when some believed Twain was only writing so that he could get out of debt, stay out of debt, and rebuild his decimated savings. Much of his work from this time is considered messy and not important to Twain’s established canon. However, A Double Barrelled Detective Story is a unique work, and worth a look. This satirical story follows a woman who discovers that her son has a superhuman sense of smell. She decides to use this power to find her husband, who was abusive when they were together and is unaware that he has a son, and kill him. Along the way, a handful of colorful characters are introduced, including none other than Sherlock Holmes. Twain’s detective story is a satire jabbing at Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s meticulously thought out crime dramas by throwing logic to the wind and telling a story with all the drama of an original Sherlock Holmes piece, but much less planning. A Double Barrelled Detective Story was not received well by Twain’s contemporaries, or the general public, who largely seemed to miss his satire. While this story isn’t one of Twain’s most famous, it is worth a read. The edition available in the UNCA Special Collections is formatted uniquely in that each page of text is summed up in the margins with a word or two. For example on page 95, the margin simply reads “Sherlock Holmes!”, which adds to the intrigue and humor of this story.

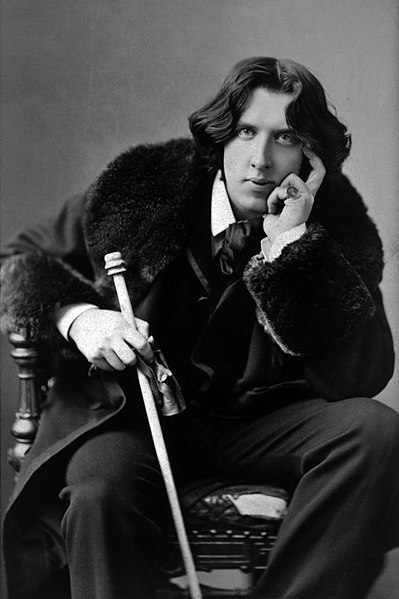

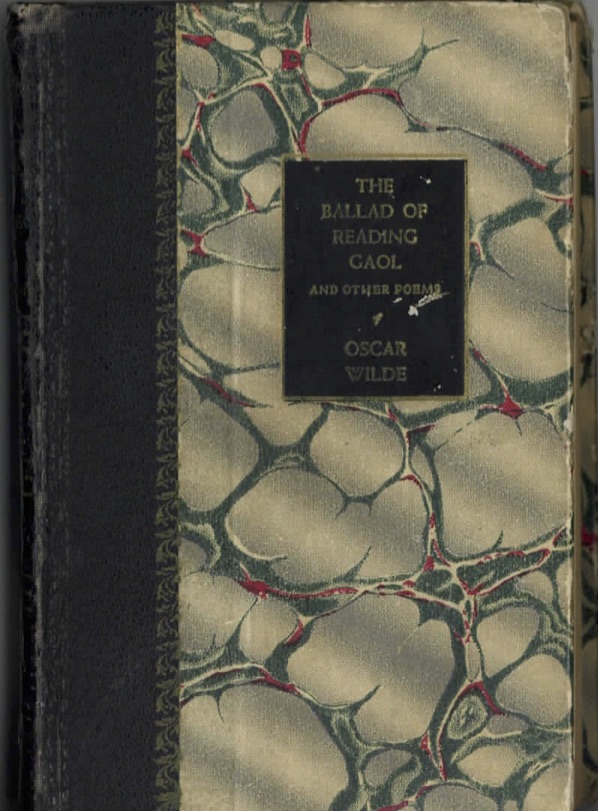

The Ballad of Reading Gaol and Other Poems

Oscar Wilde

Content warning: homophobia, imprisonment

Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde was born on October 16, 1854 in Dublin, Ireland. He was an Irish poet and playwright, and was well known for his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891). His mother was also a writer, and his father was a doctor. Wilde was a leader of the Aestheticism movement in England, which promoted the idea of “art for art’s sake”. In 1884, Wilde married Constance Lloyd, and they had two children. The last ten years of Wilde’s life were most fruitful to his writing career, he wrote and published Dorian Gray, and his society comedies which included A Woman of No Importance (1893) and The Importance of Being Earnest (1895). The central theme of many of his works was the exposure of a secret or sin that someone was hiding, which usually ended badly. Wilde himself was known for his “reckless pursuit of pleasure” in life (Britannica). In 1891, Wilde met Lord Alfred Douglas, whom he started an affair with. Douglas’s father, upon finding out about their relationship, accused Wilde of homosexual activity. Wilde attempted to sue Douglas’s father for libel, but his case fell through and Wilde was arrested and made to stand trial. He was found guilty in 1895 and sentenced to two years of hard labor. Most of his sentence was served at Reading Gaol, and his time there left him with irreparable health issues that plagued him for the final years of his life. After his release in 1897, Wilde published The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898), which expressed his concern about inhumane prison conditions. He died in 1900.

Reading Gaol was a prison in England known for its harsh conditions. While imprisoned, Wilde was only allowed to write letters, but upon his release he wrote and published The Ballad of Reading Gaol in response to what he had endured for the past two years. He details the shame and pain he felt while imprisoned, and the brutal conditions he and the other prisoners faced on a daily basis. He mentions other prisoners, such as Charles Thomas Wooldridge, who was a murderer and was sentenced to death by hanging, which Wilde also recounts in his poem. UNCA Special Collections has a small copy of The Ballad of Reading Gaol and Other Poems, published in 1951, well after Wilde’s death. This edition features black and white illustrations by Louise Phillips that accompany the poem, and make a powerful addition to the content.

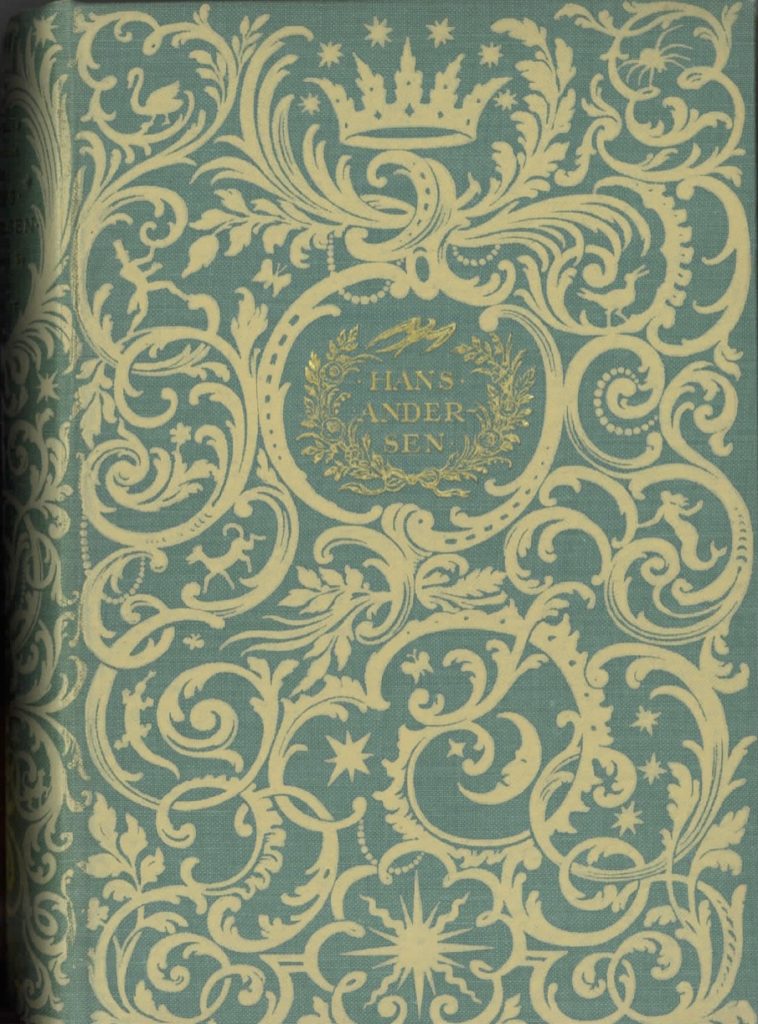

Fairy Tales and Legends by Hans Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen is a well-known and well-loved writer of fairy tales. Born in 1805 near Copenhagen, Denmark, Andersen was a prolific writer, and his work is renowned in many countries all over the world. He also wrote a number of novels, plays, and poems, which are less popular. Fairy tales most people would be familiar with, such as “The Princess and the Pea”, “The Little Mermaid”, “The Snow Queen”, “The Emperor’s New Clothes”, and “The Ugly Duckling” are all works of Andersen. Some of his stories end with optimism and a favorable outcome for the characters, but others end unhappily like many Grimm’s fairy tales. Andersen was willing to engage with less than perfect outcomes in children’s literature, which is part of what made his stories compelling to adults as well. UNCA Special Collections has an illustrated copy of Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales, published in 1948. This edition features a beautifully designed cover, and nearly fifty stories with illustrated pages throughout.

Sources

Agnew, Lois Peters. “Chapter 2: De Quincey’s Life.” Thomas de Quincey: British Rhetoric’s Romantic Turn, Southern Illinois University Press, 2012. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unca/detail.action?docID=1354633.

BBC – History – Historic Figures: Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900). http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/wilde_oscar.shtml. Accessed 17 Apr. 2019.

“Bertolt Brecht | German Dramatist.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bertolt-Brecht. Accessed 10 Apr. 2019.

Foundation, Poetry. “Bertolt Brecht.” Poetry Foundation, 10 Apr. 2019, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/bertolt-brecht.

“Hans Christian Andersen | Biography, Fairy Tales, & Books.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hans-Christian-Andersen-Danish-author. Accessed 17 Apr. 2019.

“Oscar Wilde | Biography, Books, & Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Oscar-Wilde. Accessed 17 Apr. 2019.

Schiller, Francis. “Thomas De Quincey’s Lifelong Addiction.” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, vol. 20, no. 1, 1976, pp. 131–41. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1353/pbm.1976.0009.

Twain, Mark | Gale Biographies: Popular People – Credo Reference. https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/galegbpp/twain_mark/0. Accessed 17 Apr. 2019.