By Trevor McKenzie, W. L. Eury Appalachian Collection, Appalachian State University

This article appeared in the Volume 1, Issue 3 Winter 2020 issue of the Appalachian Curator. Click here to view a PDF of the full issue.

It is exactly the wrong time of the year to dig ginseng, making it the perfect time to dig into the W.L. Eury Appalachian Collection’s holdings concerning “The Divine Root.” This summer, the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, held June 24-28 and July 1-5, celebrates the traditions and folklore surrounding American ginseng, one of Appalachia’s oldest natural exports. The event will bring together a wide array of people, ranging from ginseng gatherers still using time-tested traditions in harvesting the wild root to farmers engaged in large-scale production of ginseng to exporters who ship the root from the mountains of Appalachia to locales around the world. Since the spring of 2019, interns with the Smithsonian Folklife Institute have conducted field and archival research to contribute to the programs held at this year’s Folklife Festival. As one of these interns, I forsook the shelter of the forest for the rolling stacks of the Eury Collection, finding documents and recordings, which add context to the root’s significance in Appalachian life and lore.

Beginning the 18th Century, trade of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) has connected forested hillsides in the Appalachians with

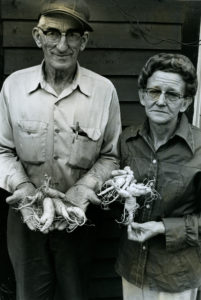

the wider world. The plant has traditionally had appeal in Asia, due to its possessing different medicinal properties than Asian variants of ginseng. Cherokee traditions tell that the root possesses a supernatural quality, allowing it to evade diggers unless they have the assistance of a spirit to guide them.[i] In the September 1977 article “The Elusive Root,” The Plow, a now-defunct southwestern Virginia magazine that focused on mountain life, community, and environment, celebrated the ginseng cache of “‘Sang Hunters” Lee and Bonnie Ashlin of Sugar Grove, Virginia. “[Lee] Ashlin says he has the best luck finding the root in ground that’s not too damp,” recorded The Plow, “but with dried ‘sang selling for about $100 a pound, that’s about as much as he’ll say about the place he found his pound and a half of ginseng.” The Plow (Periodical) collection contains the original photograph of the Ashlins holding the piles of roots shortly before trading them for cash. The photo and accompanying article are a perfect window into the long history of mountain people engaging with the global economy while making use of resources on their own land.

In contrast to the Ashlins’ homegrown story of success, the letters of E. B. Olmsted reveal the interest of the corporate world in Appalachia’s ginseng. The letters detail the attempts of Olmsted, a Washington, D. C. businessman, to set up a ginseng empire in southwestern North Carolina in the late nineteenth century. Entering the mountains near Murphy, North Carolina in 1870, Olmsted attempted to manipulate and control the trade of ginseng. Unfortunately, his outlook on mountain people was largely shaped by stories published in 1860s magazines, focused the curious and primitive practices mountain ginseng diggers. Olmsted also believed that, in the wake of the Civil War, he would be the economic savior of the region, inspiring the gratitude of mountain people while making his fortune. The reality that greeted Olmsted in the mountains revealed a people who, rather than being isolated and ignorant of the worth of mountain roots, already had well-established connections with ginseng exporters. Olmsted’s letters, largely to his creditors at the New York firm, Lanman and Kemp, are pitiful to read and chart the gradual failure of his unborn ginseng enterprise. At certain points, the businessman expresses his annoyance at mountain people’s business savvy and their failure to play into his money-making plans. Olmsted’s letters are an amazing resource, connecting the history of the ginseng trade with the stereotypes of mountain people as they formulated in the post-Civil War era. The correspondence to his New York backers also displays the heavy financial interest of outside investors in natural resources in the Appalachian region, concurrent to similar interests in coal and timber.[ii]

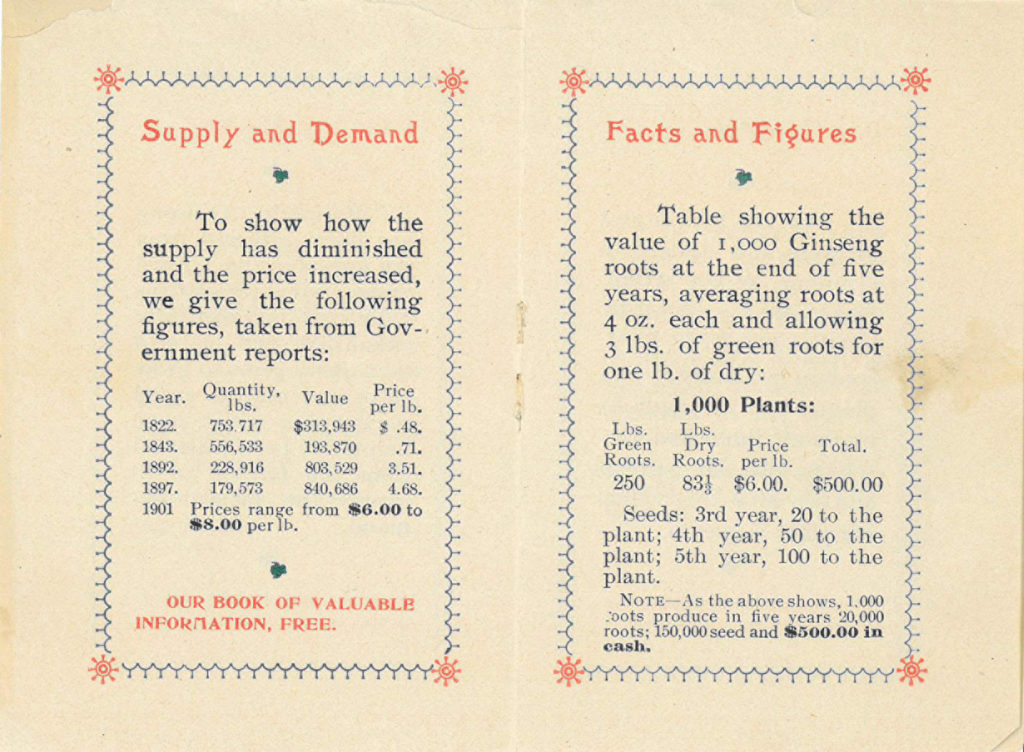

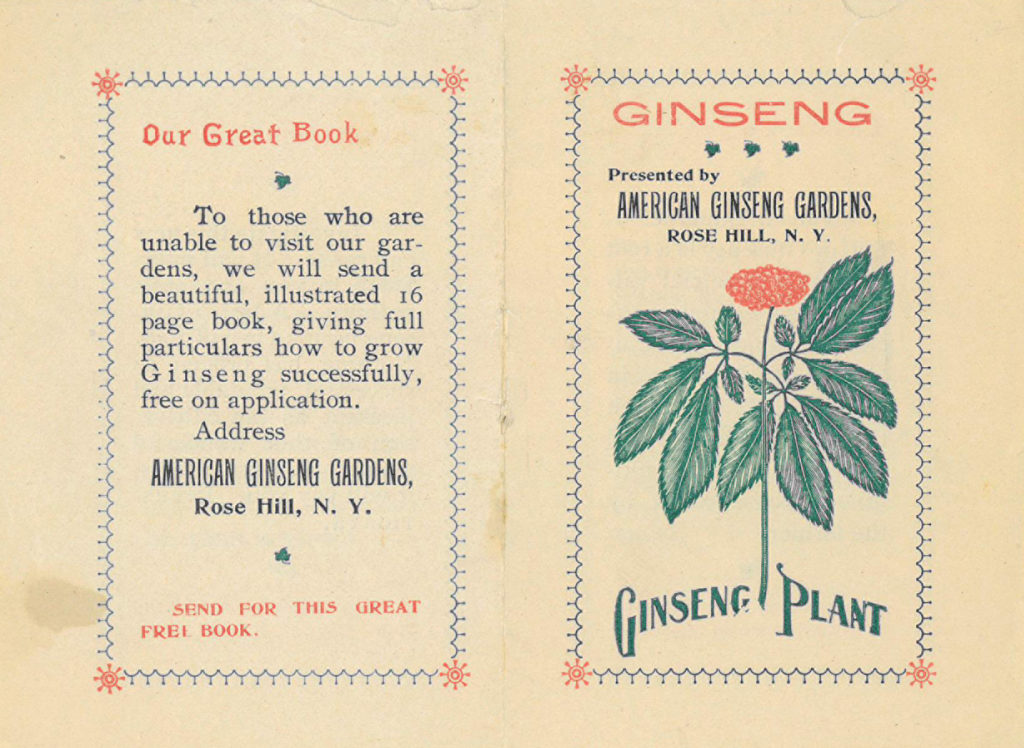

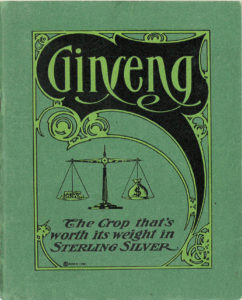

During the latter part of his time in the Appalachians, Olmsted appears to have picked up the pamphlet “Ginseng: The crop that’s worth its weight in sterling silver.” This New York-produced “how-to-guide” on the ginseng trade connects with another collection in the Eury manuscript collections, Exporting Companies’ Information and Ginseng Cultivation papers. These papers contain newsletters, correspondence, instructional articles on the maintenance of ginseng, and price lists for dried roots, all produced by between 1908 and 1916. The correspondence in this collection shows the continued interest of northeastern-based businesses in North Carolina ginseng, with letters from exporters H. A. Schoenen (New York, New York), Belt, Butler and Company (also New York), and Newtown Producing Company (Bucks County, Pennsylvania). Conversely, the small collections of S. V. Tomlinson’s Price Lists of Roots and Herbs and Botanical Receipts sold to Todd Drug Store and R.T. Greer and Company, focus on communities engaged in the buying and selling of botanicals in Wilkes and Watauga counties.

In addition to the above manuscript materials, the Eury collection also holds many oral histories related to ginseng hunting and exporting. The William Lightfoot Collection of Student Papers contains the transcript of a conversation with a southeastern West Virginia ginseng hunter, Fred Prichard. Interviews with Mr. and Mrs. E.R. Duvall, Ed Cullen, Elizabeth and William Hartley, all focusing on the history and community of the herb trade in western North Carolina are held in Appalachian State University Oral History Projects. Perhaps the most significant oral history on buying and selling of ginseng (and other roots and herbs) is a recording of Butch Wilcox of Wilcox Drug Company, also in the Appalachian State University Oral History Projects. This multi-generational family company, established in Boone, North Carolina in 1900, was, according to Butch, “the largest American buyer of botanicals” by the mid-1970s. Though it is no longer in operation, Wilcox Drug is still remembered by the wider herb trade community, with many of those who worked for Wilcox now operating successful businesses across the southeast.

The celebration of American ginseng at the 2020 Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, D. C. this summer will engage audiences with the living history of an interaction between a plant and people. On the eve of this celebration, the Eury Collection at Appalachian State University continues to collect and document the ginseng’s significance in Appalachian folkways and economies. It is hoped that some of the materials from the Eury Collection will contribute and add context to the programs held in Washington, D.C., and further help the public dig into the history and culture of the “elusive root.”

[i] For more on this history see David A. Taylor’s The Divine Root: The Curious History of the Plant that Captivated the World (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2006)

[ii] For more critical analysis on Olmsted’s letters see Luke Manget’s awesome article “Sangin’ in the Mountains: The Ginseng Economy of the Southern Appalachians, 1865-1900” (Appalachian Journal 40.1-2, Fall 2012/Winter 2013).