By Gene Hyde

This article appeared in the Volume 2, Issue 1 Spring/Summer 2020 issue of the Appalachian Curator. Click here to view a PDF of the full issue.

Catherine MacPhee is the Trainee Archivist at the Skye and Lochalsh Archive Centre in Portree on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. I met Catherine while visiting the archives in Skye in June 2019 and interviewed her at her home on Skye via Zoom on May 8, 2020, while she was on furlough from work due to the pandemic.

Gene Hyde: Hi Catherine. I wanted to ask you some general questions about your work in the archive, picking up on what we discussed when I visited there last June, and then some more questions that explore the common threads between what you do as an archive in the Highlands of Scotland and what we do in archives in the Highlands of Southern Appalachia.

You are a Trainee Archivist at the Skye and Lochalsh Archive. Can you tell us about your archive on Skye and its relationship to the Highland Archive Service?

Catherine MacPhee: The Highland Archive Service comes under a charity called High Life Highland that was formed in October 2011 by The Highland Council, the local authority, for the whole region of the Highlands and Islands. Within High Life there’s nine different sectors. You’ve got things like archives, museum and libraries, so we come in there. You’ve also got things like music tuition, as well as leisure- that’s gyms, swimming pools, and sports. There’s youth development, which works out well with where we’re based, as well as adult learning. So its’ a very broad scope of services we put out for the whole Highlands.

Within the Highland Archive Centre there are four archives. The largest one is in Inverness. That’s a purpose-built one that’s 10 years old now. They’ve got a really good conservation unit and a really good team of staff, so everyone’s got quite unique skills. We’ve got one in Lochaber, which is in Fort William. It’s a small one, probably about the same size as us. They are covering that area, so there’s a wee bit of crossover between ourselves. They’re very heavy on Jacobite stuff and local family estates, they have some of the best collections -in my opinion. Then up in the very north of Scotland we’ve got the Nucleus that’s covering Caithness and the north of Scotland, they also hold all the Nuclear Archives for the UK. And then there’s ourselves on Skye, and we cover Skye and the mainland Locahalsh area.

So it’s quite a big area to cover, for all of us, but it works. We can pick up the phone, and it’s obviously changed during the pandemic, using Skype and Zoom and everything has helped. We’ve been able to dial up and chat with somebody, whereas before it might have been a couple of emails, or I’ll phone you after lunch, so now we can just instantly call and ask “can you help me”?

The Skye Archive was around for quite a while. It was part of the museum service back in the early 90s and its kind of developed from that. So we do have quite a mixture, as you saw when you were there. We’ve got archeology, paintings, prints, plus the actual archives, so it’s quite a blend we have in comparison, say, to Lochaber. It’s a really good way for us to work being part of that bigger charity. We’re connected to libraries and museums and we all kind of work together. It’s complicated, but it works.

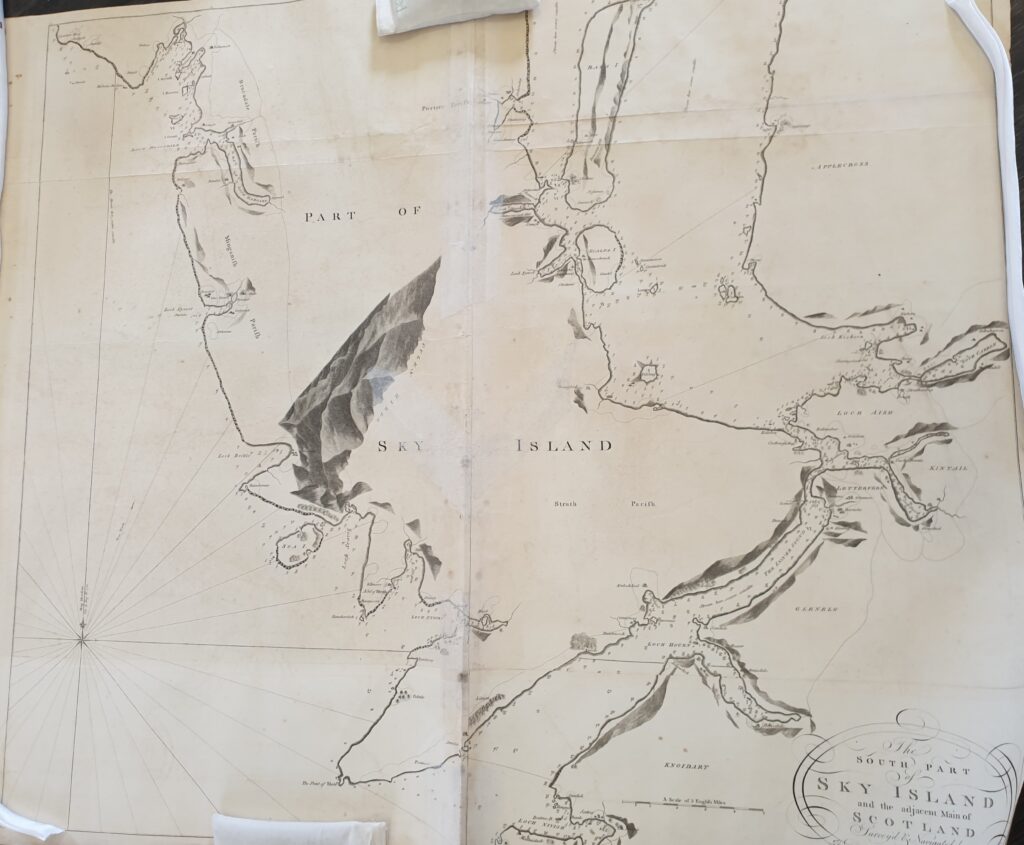

We do cataloging and everything at Skye. Any conservation work is done at Inverness– for instance I’ve got four maps there from the 1740s at Inverness now to have conservation work done to them. So anything like that Richard (Aitken, Senior Conservator at Inverness) will assess remotely and then take over if it needs it.

Generally, if we get a collection in and it’s just basic cleaning and no real conservation work needed we will clean it up, catalog it, and get it all the way there. And if we need help we can reach out to our colleagues in the other offices and ask for some support. Inverness is the main hub. For example, all the medical records for the Highlands are stored there. So if we get somebody who comes into Skye, for example, and wants to know about a historic hospital we can get in contact with Inverness and they’ll scan it and send it over. So it works.

GH: What is your core mission at the Skye archives?

CM: (Laughing) Well, we changed quite a lot over the last month or so. Our core mission – I’ve been 18 months on the job – firstly conserving and making the archive collections accessible, while continuing community development, for one. Working with local trusts, the way Skye is split off into different parishes and connecting with people there to keep adding to the collection as well. Working with local community groups who are organizing little historic hubs in there own area, so I’m working with them so they have replicas rather than original material out. And just really making people realize the importance of the culture here and how we capture what’s happening now. We are so lucky in what we’ve been given and what we’ve got already, but it’s just that constant adding to the collection and just making people understand it isn’t all about the elite. It’s about the average person who lives here. Doesn’t matter who you are, it’s about your history and your culture. And for us it’s just recording that at the moment.

For example, before lockdown happened, I’d been speaking to a local art group about doing a collaboration connected to the sea. Out of that it came to my realization that we really have nothing on the fishing industry. We’re an island! (laughs) So that’s opened up a conversation and then, bizarrely through everything that’s been going on here, local fisherman are now selling to locals rather than everything going to Spain. So that’s what happens. The fishing boats come in and probably 80-90% of their products would go to the Spanish market. That’s the way it is. My dad was a fisherman, and that’s how it’s always been. But now locals are buying and eating it more now than they were three or four months ago because of the pandemic. That’s really good. But it’s even recording how these guys are fishing. So I’ve spoken with a few of them about taking photographs, taking videos, just take take take, and if you want you can deposit that.

That’s opened up other conversations about the historic side. We’ve got older parts like salmon fishing, where there were older papers and documents where people were recording it. But stuff about the average fishing boat? There’s not much. That’s something that’s come out in the last few months. So I think one of the key focuses is grabbing these smaller groups in society. Women in archives – there’s not much in Skye or the Highlands. And also Queer archives, there’s not much on. So there’s been a kind of wider scope across the highlands. Our colleagues are speaking to minority groups and telling them “this is what we do, this is what we want to get in.” Just capturing that.

There’s a Bangladeshi community that’s been here over 15 years. We have nothing pertaining to them. I know some of them. They speak Gaelic. They live here, they all have different jobs. I’ve spoken to them and explained what we do. It’s just getting them in to see how we would use the information and what we gather would be a better understanding for them.

GH: It sounds akin to some of the community archiving projects that are popular in the States. For instance here in Asheville there’s an archivist working closely with the African American community, trying to document them and get their stories, have them come in and share their photos. You get a digital image and they keep the original. That kind of stuff. Is this kind of community archiving thing going on there?

CM: One of the projects we’re doing – it was actually the last event we did before everything turned upside down – we were approached by a local community group in an area called Minginish on Skye. That area’s got quite a long history. It was cleared in the Highland Clearances really early, like in the 1820s to make way for Talisker Distillery. Then they repopulated after the First Word War. There was land that was bought over by the Board of Agriculture and they repopulated it with people from other islands. So a separate community grew out of one that had been there before, people from Lewis and Harris, the Western Isles. They repopulated that area.

That community got in touch with me and basically said, “we’re wanting to capture oral history and that community before it vanishes”. My Mom’s family are from the people who settled there, for the last hundred years they’ve been there. So we went up and had an event and asked them to bring photographs and whatever they wanted in. We had an introduction with a slide show on. I explained what we do and how they could use it as a community. We spoke about oral history, and how not to be scared of the equipment and don’t get too bogged down in the paperwork. You leave that and we’ll deal with everything there. But we did image sharing that day. We scanned a few things with them that day, but the conversation was kind of like an afternoon tea. There was about 80 people there, myself and a couple of community members. It was just a conversation. The stories we got were unbelievable. Just fantastic. And straight away they said “we want another one.” But we’ve hit this pandemic. So we’ll just wait.

And after that, obviously, word got around – it’s a small island. We’ve had two other community groups get in contact and say “can we do that to get people engaged?” And it’s also making quite clear that it doesn’t matter if you’ve lived there your whole life or if you’ve just moved there. It’s still where you live, and it’s still the culture and history. So it’s making sure it’s quite inclusive for everyone. We do have a lot of people who’ve moved to Skye from other areas. It’s making them culturally aware of what was here before, and getting them involved. I think it just makes people connect a little bit more. It’s certainly the way we’ve done it where well let them take ownership of the project in an area. We’ll give them guidance around oral history, how it can be deposited, and how we’ll look after it. But we let them gather, naturally, themselves. That’s the work we were doing at the beginning of this year.

We were going to have an oral history workshop where members could come in and learn how to have that conversation, how to record, and the importance of things like don’t go home and plug it into your computer, just bring it straight here, to get around the technical side. That’s just been shelved for now. We got funding for that from the Scottish Book Trust, because we’re a charity we can apply for funding. So we’ll organize events where community members can come in and learn skills, and see us and meet us, then we’ll go and help them set up, and the archives will come to us. Hopefully (laughs).

GH: A professor here is doing the same thing with the LGBTQ community in Asheville. We have a very large LGBTQ community, which is not well documented. It’s been interesting in Appalachia, the awareness of starting to document that community which was, 20 years ago, not “out” yet, to a large extent.

CM: Same here.

GH: You’ve talked about this to some extent, but to give our readers a better idea of what you do – what’s a typical work week like.

CM: Honestly, you do not know what’s going to come through the door. I would say we’re more aware of what will happen during the busier tourist months. It’s busy all year, but Easter to end of October is peak. During that there’s a lot of ancestral tourism, so that would be people from Canada, the US, New Zealand, and Australia. Those are the four main places where people went who were removed from Skye. They come back to do their genealogy, retrace their ancestors. So those weeks you know you’re going to be busier. There’s going to be a lot more explaining of history, and that records don’t exist for certain time periods. So you become almost automatic for those weeks. You know the phrases and what you have to explain. You know the go-to points and where we can find them.

But like any other week you could be dealing with anything. Somebody could be coming in with a deposit. Somebody came in one day with six big bags full of archives, with no warning. Just appeared! That can happen mid afternoon, and there’s only two of us. So I just went to another room.

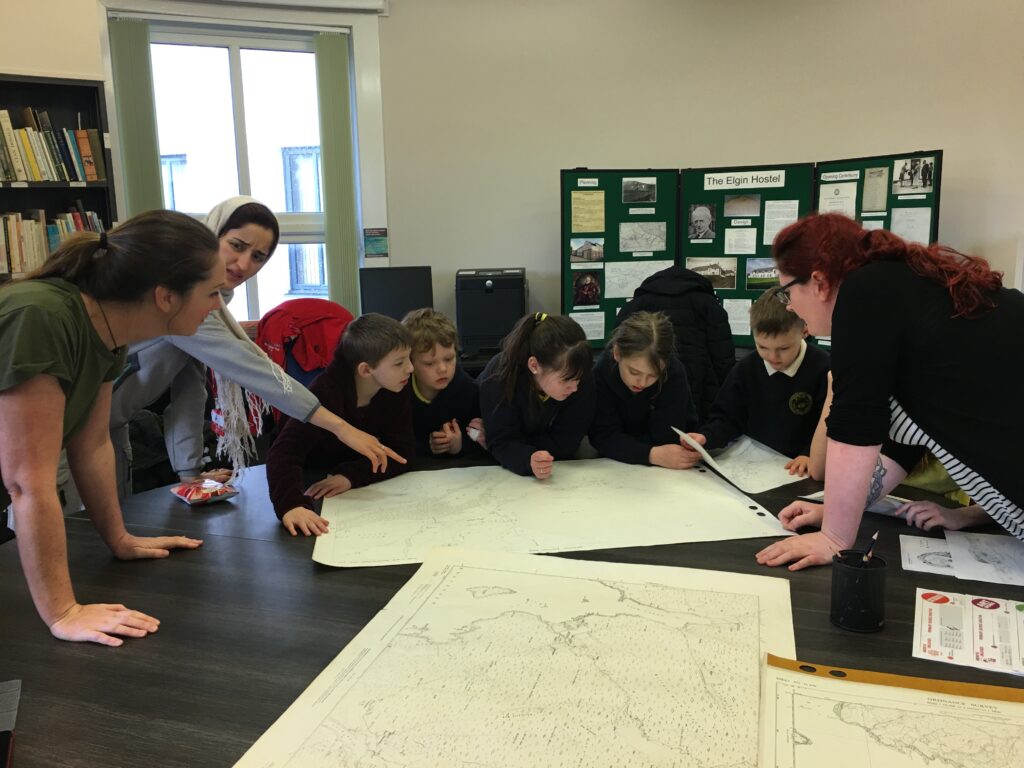

A typical week could be having a school group in. We have school groups come in and look at the exhibition. We might be asked to create something for them to look at. You might have a class on a Wednesday. We’re shut to the public on Wednesdays but we’ll run a class, which is free, for people to come from the community to learn about where they live. A lot of that is based on maps, introducing them to archives. Some of the week we try to allocate to cataloging (laughs). We very much go with what happens, we’re quite reactive to who comes in the door. Over the quieter months you get a lot more researchers, maybe researching for books, PhDs and local people writing for wee publications.

We get a lot of remote research as well. So prior to the pandemic we were doing some work with a couple of TV companies that were going to come and film here, so we were doing some research for them. I tend to do that research behind the scenes. So, yeah, it’s so variable. I mean one week we had people in researching eagles, and someone else researching the growing of flax pre-1700 on Skye. You just never know. But summer is mainly genealogy and family history. It’s great. You meet people from all over the world. There’s no typical week.

Looking at my calendar, or how it should have been, obviously today is VE day when people are celebrating the end of the Second World War. We had planned a pop-up in the village with our local community, where we had a slide show of oral history and images, where we had people reminiscing as children growing up here during the war wearing gas masks. We had a projector and banners… and it’s all just sitting back at work. So it’s very much changed. No week’s ever the same.

GH: That’s a nice segue into something you and I were talking about when I was there, being an archivist dealing with people from outside the region who have stereotypes and preconceived images of the region. Can you cite some examples of where you’ve worked with people to educate people about the region and the reality, versus the perceptions they bring with them that are not correct?

CM: One of things I get asked a lot is: “do you get educated here?” Right where we are – and we’re next to the school! A lot of people assume that if you’re from somewhere as remote as here in Scotland that you are uneducated, and that you don’t really achieve much. There’s a phrase called “teuchter” that was used to describe a “thick Scot.” We embrace it now as our own word. But I think there’s still a stigma behind that if we’re doing a job like archives, or anything that’s classified as academic or professional, then you can’t possibly be from the islands. Which is insane, because the amount of talent from artists, writers, engineers and scientists that come out of Scotland is unbelievable.

There’s work that we’ve done even locally to dispel cultural differences. We do a class called “Where do you stay?” The wording around that is kind of difficult for people. That looks at old maps, place names and what they mean, and what happened when the place was cleared out during the Clearances. I do spend a lot of time in the summer when people come from all over the world explaining their version of Scottish identity, whether their family left here 50 years ago, or 300 years ago, or 400 years ago. It’s so different than mine. Completely different. I would say, very much, that people still identify with clans, tartans, and imagery. And I have to explain to them that that’s not my version of being Scottish – the whole tartans, shortbread, and “Outlander” – dare I say it. It’s just not who we are, certainly not me, anyway (laughs).

So we sit back and explain how Scotland and the rest of the United Kingdom joined together, and what that means for our identity today over the course of several wars and royal family influences. There is this misconception that we were all living in caves or small stone houses, and the Highland Clearances were a good thing because it got us out of poverty and we all benefited from it. There’s this myth that we’re all running around in tartans playing bagpipes when we’re not. You may well see a vison of tartan and bagpipes on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh. It’s a huge difference. Some people love that culture – we sell it.

We spend a lot of time dispelling the myths, and really reading into what happened, how dark the history was for a long time. People want to see it as this romantic place where they can come and connect with their roots and get a good feeling doing it. And I love to be able to say to people, “this is where your family lived, let’s go visit it” and go and actually see how beautiful it was. I make them realize, if we can prove through records, that they weren’t living in a hovel, they were literate, they could write, they were poets, they were bards, they were scientists, they were doctors. I think the perception is we were cavemen. (laughs)

So we’re trying to stop that, and make people realize that there’s a lot more going on here than you think. It wasn’t a case of clearing out these heathens and moving them to better lands. But it’s been portrayed that way by the Empire, hasn’t it?

GH: Yep, class and money.

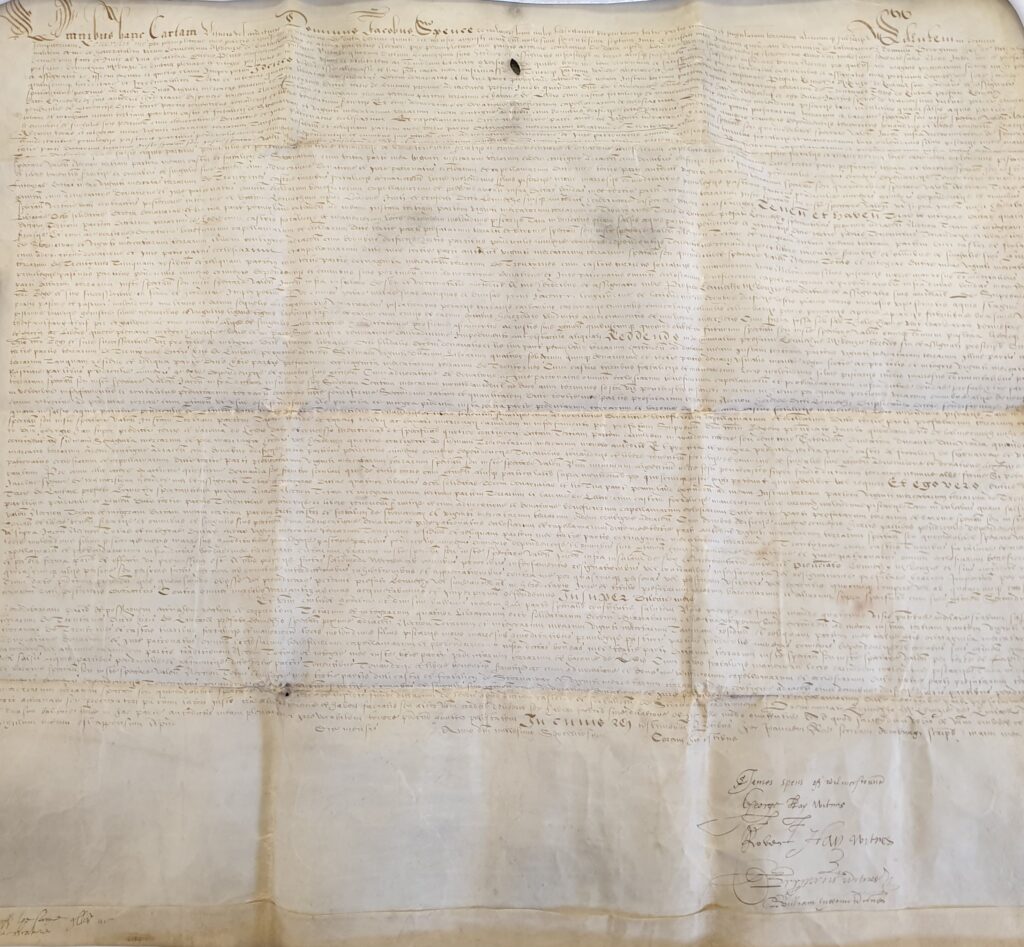

CM: Class and money. That’s one of the biggest things. Archives can be very elitist. Especially in Scotland, especially some of the records we have. We have some estate papers from landowners, absolute tyrants, some of them, one of them was particularly nasty. But if we didn’t have these records there would be so much missing from history. There’s a bit of untold history in that repository at work. There’s so much in there we’ve been finding, just little snippets. We were doing a big cataloging project a few months ago. The cataloging’s not finished, but there’s a letter in there from 1854 from another island to a landlord here, and it’s signed by 15 crofters. The view of men living here at that time was that they were illiterate. The way it’s written, is just amazing the way they describe what they’re doing. It’s fantastic. There’s a lot more going on here than people think.

GH: So in the Highlands you lived in caves, played bagpipes, and fought with each other. In Appalachia we lived in run-down shacks, feuded with each other, and made illegal alcohol. That’s what we did.

CM: We’re good at making moonshine, though! (laughs)

GH: What are your biggest challenges as an archive, outside, of course, of the pandemic?

CM: So if you look at the Highland Archives as a whole, the LGBTQ+ or Queer archives is certainly something we’ve been trying to build on as the Highland Archives Service. Through conversations with each other and as a community, it looks like it might need to be led as a collective rather than individually. There’s places like where I am, in Skye, where there’s probably more of a stigma and probably more of a secretive community that there would be in Inverness, which has a bigger population. That’s a big challenge for us.

Obviously we’re part of a charity, so we come under the High Life Highland, so it’s always looking at new ways to generate money for the charity. That can be things like selling images and doing research. That challenge is always in the background.

I think, for us, it’s making people aware that archives are for everyone. I’ve had people arrive, look in the door, and say “is it OK if I come in here?” And I’m like “Yeah, of course.” I’ve spoken to other archivists in Scotland about this and there’s still the stigma of “archives aren’t for me,” and it’s back to that elitism. We genuinely think that the more minority groups we get in, and the more women’s groups, and the children’s groups, and men’s groups that we meet and bring in, the more people will come through the door. I would say that’s probably the biggest challenge is making people realize it’s for everyone.

And it’s the perception that they aren’t allowed in the archives. A guy came in one day and said “I didn’t really do well in school.” I said “that doesn’t matter whether you went to school or not. You just come in.” And he’s in every week now, and he’s always got questions. It’s fantastic, and it usually puzzles us for a while to get an answer because he just knows stuff that he’s learned from people. So it’s things like that.

GH: So to the big elephant in the room. How are you doing as an organization, and as an individual, with the pandemic and the lockdown?

CM: As things starting unfolding in Britain we were very well supported from work so we had enough archival work to do at home. They made sure that staff could work. I have a work laptop I can take everywhere, but my assistant doesn’t, so they made sure that she had access at home. We loaded up things like old catalogs. Just those kind of things that you’d say, “yeah, we’ll get around to re-doing that,” anything we could take home on a USB stick or access through our drives, just work like that that we could do.

We built this up and had all these plans to take all this work home, get it done, and go into the network. We’ve got the building secured. Suddenly we jumped onto these platforms to talk to each other, which is good. But then we quickly realized we had to adapt. Everything we planned to do just went to the side, and we were looking at ways we could support the communities during this. For example, one of our colleagues has been doing these learning videos for our Facebook pages, and it’s using collections we already had scanned in and digitized, and doing classes on them. Just talking about what archives are. She did Jacobites this week, and each week was a different theme. So we’re looking at what we can do to support people on there.

Most of the staff are furloughed, and then we get routed back in so people can get time off and get a bit of a breather. We’re definitely taking time to think about how it’s going to look after. We’ve had open communication from everyone in the company, which has been great, and there is loads of support there if we need it. Working from home was challenging from the beginning for everyone. When you’re not physically in a box of dusty old records –you’re so used to “oh, I’ll just have a look at….” You’re thinking, “what have we digitized. What do we have on these drives? How can we use this to support these people?”

One thing we were very cautious of, being in a rural area, was isolation. We get groups of older members of the community that might come in and see us. So they’ll all come from rural areas to the largest Highland island for a day, and they might all go out for lunch, then come and see us for two hours, and then they’ll all go down to the outdoor centre and do other activities. It might be like a ceilidh, or sometimes they’ll have Gaelic story classes or such. So all these people who live on their own out in the community are now completely on their own and all these activities have been cancelled.

So we’ve worked on ways to still engage with certain groups. We’ve made story boards, just a card with images and archival documents, and everyone from each Centre gathered work we had scanned in, made them and laminated them so they could go out to people. So there’s things like that we did so that we’re still supporting people from the archives. So there’s obviously today, VE Day, so there’s stuff from the archives online. Just adapting, using what we’ve got, and realizing that we don’t have enough digitized (laughs).

GH: That has been apparent in the last couple of weeks.

CM: Yeah. I’m mean we’re very lucky. We’ve got Am Baile, which is our digital website with images, so we’ve got a huge resource there. But it’s more actual archival documents. And I don’t know the collections at Inverness like I know my own, I know a few that I’ve been shown when I went there, but I just don’t know them like my own. So when you go back into work you’re thinking what can you use to support what activity you have going.

Our family historian at Inverness has been super busy doing online consultations with people. So that’s a new way of working, which is great. We’re definitely getting together, chatting, and coming up with new ideas. All these plans to reorganize catalogs haven’t happened yet. It will come.

For me, it’s been a bit surreal. We had all these big plans, we’re going to do this, we’re going to do that. And once it happened we locked the doors. That was really emotional. We were both saying that. Locking the door, and not knowing if you were going to get back in there. It’s all those little boxes of treasure, all that stuff that you do all day, all that different way of thinking and it’s just gone.

GH: We are not allowed to go to work and work, but we are allowed to go and fetch things to do at home. We’re working from home, and when my assistant went in she almost broke down in tears she missed work so much.

CM: I don’t know if you’ve seen our stuff online. We started a campaign at the beginning about people keeping diaries. So that’s something Fiona, the senior archivist at Inverness, and myself were chatting about “how do we, as archivists, record this.” What’s happening in our own heads, and what we’re doing, and how that’s adapting. But also if we can get people to start recording diaries, it’s good for them, it’s good for their mental health, and if they chose to deposit them with us, that’s fantastic. We have loads of support locally. The local paper, which is now not printing, they did a huge thing for us. And I did a radio interview locally as other colleagues did. So we’ve done stuff to report that. And it’s really weird not being at work to gather examples, so we had a few diaries scanned in and used what we had. But, yeah, I find it really strange not being in work.

2 Comments

anthony J Grindrod

Catherine

Do you have any maps which would show the extent of the Bracadale Estate?

Who are the current owners – Scottish Government ?

Professor George Youngson

Hi Catherine.

As a colleague of Prof Rhona Flin,could you tell me how I might access some of “Angus Og’s” previous daily record cartoons

thanks

George Youngson