This article appeared in the Volume 5, Issue 1 Spring/Summer 2024 issue of the Appalachian Curator. Click here to view a PDF of the full issue.

By Trevor McKenzie

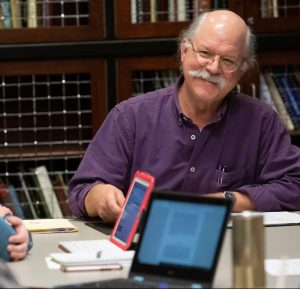

Gene Hyde is an Appalachian archivist, writer, poet, and advocate for the importance of collecting and preserving materials that document people and places in our mountain region. He began his regional studies career with an MA in Appalachian Studies from Appalachian State University and dove into archives with an MS in Information Science from University of Tennessee. Hyde has been an integral part of building regional special collections at Lyon College (Ozarks Collection), Radford University, and at University of North Carolina Asheville. He is a key member of the Appalachian Studies Association’s Special Collections Committee and is the founding Editor of The Appalachian Curator.

The following is a conversation between Hyde and Trevor McKenzie, Director of the Center for Appalachian Studies at Appalachian State University. McKenzie previously worked in the archives of the W.L. Eury Appalachian Collection and considers Hyde a mentor in regional studies and special collections. In this interview, Hyde reflects on his career, his path into Appalachian Studies, and his perspective on archiving and the function of special collections in a historically misrepresented region. Gene, his partner, Barrie Bondurant, and his many friends and colleagues will celebrate his retirement from UNC Asheville this August.

TM: Gene, I know that you’re not originally from Appalachia, however, this place has become such a central part of your life and work. You are rooted in this place and have played a key role in the development and curation of spaces that preserve its history. What was your path into the world of Appalachian archives and Appalachian studies?

GH: Well, first, it’s my path into Appalachia. I was an Air Force brat, and when my family came back to North Carolina in the 60s we lived in the suburbs of Greensboro. As a place—the suburbs—they just weren’t meaning much for me. I initially started coming up to the mountains with a friend of mine’s father, who was from Morganton. I fell in love with the mountains and spent as much time here as I could. I dropped out of college in my 20s and moved up to Boone in ’84 and didn’t want to leave!

TM: What brought you to Boone?

GH: Really, all I knew was that I needed to change. I knew that living in the Piedmont and suburbia wasn’t working for me. An existential crisis, I call it now, and I think it was. I got up here and I literally had no job, moved in with a good friend of mine. I’d quit my job with no prospects. That was the kind of state of mind I was in when I came up here.

I started washing dishes and then I started working for The Mountain Times, back when it was owned by Ken Ketchie. Ken had me distributing papers, which meant I got to drive out all through here. I went mostly into Avery county and up through there. I got to stop and talk to a lot of people. And I began to realize that there was a whole lot that I was seeing in common with folks up here that reminded me of my family coming from eastern North Carolina. My grandfather, on my mother’s side, was a farmer. My grandfather on my dad’s side was a small businessman who died my dad was young. With these family connections in mind, there was so much in common with rural North Carolina.

I was feeling that this was not a strange place. To me, it was closer to home than I thought. And when I got into the Appalachian Studies program in 1987, I began to understand that there were differences, but a lot of parallels. And I’ve always felt that the parallels are what pulled me in. I was new at trying to figure this out, but it seemed like all the pieces started to fit. In that process, my love of the place became my love of the history, the people, and the culture of the place.

TM: This is relatively early in the academic life of Appalachian Studies, within the first decade of the program existing at Appalachian State. What was it like during that period?

GH: A friend of mine, Matt Walpole, now a bookseller located in the Boone area, told me about the Appalachian Studies program. I went over and I talked to Dr. Carl Ross, who was Director of the Center for Appalachian Studies at that time. What I had to show for myself on paper, well… it didn’t really look all that good, (laughs) but he decided to give me a chance. I took some classes to finish up my undergraduate degree, which I did by taking an elective here and transferring it back to where I had been in school at Greensboro.

(looks a picture of Dr. Ross hanging in the Center office)

I guess that turned out okay, Dr. Ross! (laughs)

TM: Were there scholars or works that influenced your dive into regional studies during this time?

I think one of the first books I read was Shapiro’s Appalachia On Our Mind, about the idea of Appalachia. For some reason that really resonated with me, especially from what I had always perceived about the region. The watered down, “bunch of hillbillies” thing was always a contrast to what I was actually seeing. When I got up here and started meeting people and talking, reading that book was hugely influential. I still, with caveats and all, recommend that to people trying to understand Appalachia.

David Whisnant’s work was also influential. I was fortunate enough to get to work with his son, Derek, who worked with me in archives. Through that experience, I got to know David. Also, John Gaventa’s work. I think I started the semester just after Cratis Williams died, so I never got to meet Cratis, but it was close. It was a real bummer to miss meeting him.

TM: This sounds like a time of transition, not only for you, personally, but for Appalachian Studies.

GH: It really was in a lot of ways. While I was wrapping up the program, Dr. Ross passed away unexpectedly. I had three independent studies with Carl, and we were about—I forget—maybe six weeks into the semester when he passed? I realized I might be in trouble because nothing was written down!

Luckily, both for me and the rest of Appalachian Studies, Dr. Pat Beaver came back in and took over—she had been the first Center Director back in ’78. I went to Pat and said, “Heeeey!” (slightly apologetic, exasperated tone) and she said, calmly, “Well, tell me what you guys had going on and we will write it all down.” She honored the agreements. I finished the program thanks to her being willing to work with me on that.

TM: Appalachian Studies students often bring their own research interest or area of study to the graduate program. Did you come into the program with a focus or was that melded in the time that you were at Appalachian?

GH: No, I wasn’t very focused at that time. (laughs) I was kind of interested in, but never really focused on, the idea of folk iconography and Southern Appalachia. I’ve always liked folk religious art but never pursued that past a certain extent.

I did an internship with an Appalachian Summer, a concert and arts series run by the University. I had a graduate assistantship position that Carl Ross had given me. Local musician and folklorist, Mary Greene, was running the Appalachian Winter Festival where’d we bring in crafts people and music. I took over running that. I kind of saw the internship as an extension of arts management. I ended up working as an arts coordinator for Watauga County Parks and Rec. for a while during this time, too. So, I was very interested in that aspect of cultural arts programming.

In the final paper, which I wrote for Pat, I tried to look at how this program (an Appalachian Summer) did and did not truly serve and represent Appalachia. It was probably a terrible paper and I’d be embarrassed to read it now. (laughs) My focus was on answering the question: “What are outsiders doing for and against the region?” I could see where Pat could have taken me to task for an essentially stripped down argument or lack of nuance, but she passed me with it. So, I guess it worked! (laughs)

TM: What was your path to a career in archives after your graduate degree in Appalachian Studies?

GH: When I finished the degree, the thought that settled with me is, “I think I know the region better now and I think I want to live here. I think that I can contribute somehow, but I don’t yet know how.” About this time, I met Barrie Bondurant, who was from the Hickory area and who’d been a grad student here while I was at Appalachian. We ended up getting married, and just yesterday celebrated our 36th anniversary! Our path led us down to Greensboro for her to get a PhD.

Our goal had always been for Barrie to get a doctorate and for us to find a place in southern Appalachia. Well, the place we ended up going to was these other mountains called the Ozarks. (laughs) We ended up at a small college in the Ozark foothills in Arkansas, Lyon College, where she was a tenure track professor. I had always wanted to work in the library or to try to find work in a public radio station, so I kept an eye out for any opportunities.

I ended up getting a job in the library within a couple of couple of months after moving there. I had no idea about archives or whatnot, but Lyon College had small archive of Ozark materials. The person running that was leaving and my boss, Dean Covington, said, “Gene, you’ve got a master’s in Appalachian Studies. That’s Ozarks adjacent. You should do this!”

I fell in love with it. I fell in love with archiving and the processes involved and collecting the region and preserving it. I felt like I knew where I was going career wise, so I entered library school online through the University of Tennessee. My idea was we’d stay in Arkansas, so I started to pursue doing a thesis on Ozark Special Collections. I visited a couple of the big collections and my heart wasn’t in it. My heart wasn’t in it at all. I wanted to be back in southern Appalachia like you would not believe. (laughs)

Barrie and I both wanted to be back in Appalachia. I shifted focus and changed my thesis to a study of Appalachian Studies collections and their relationship to Appalachian Studies curricular programs. You have to pick your place sometimes and, with this project, I picked mine. I did seven collections, initially— Appalachian State, East Tennessee State, Radford, Berea, Emory and Henry, Lees-McRae and Virginia Tech. I arranged to go and do interviews with the administrators of both the Appalachian Studies programs, and the archives. Dr. Fred Hay, at the Eury Collection at Appalachian, was an ex officio member of my thesis committee.

TM: Could you talk more about your thesis project?

GH: The project traced the history of Appalachian special collections. Throughout the course of interviewing and writing, I began to see the historical importance of these collections. The importance that had always been recognized by scholars like Cratis Williams, collecting the region in order to preserve an accurate picture for scholars to use and for people to understand. I never felt comfortable as a researcher—especially in terms of feeling like I was really a strong voice outside of the field of librarianship. I did not feel I could write about Appalachia with any sense of authority since I was not from here. When I realized I could collect Appalachia, I embraced that and ran with that.

TM: Did this guide you into your work in regional archives?

GH: I ended up getting a job at Radford University in 2003, where I was hired as an acquisitions librarian. For about two and half years, I managed a $1.4 million dollar budget. By the time I left that position, I was done with spreadsheets! (laughs) I just couldn’t look at them anymore. So, I moved from acquisitions into reference and instruction. I have to say, being trained as an instruction librarian with information literacy has really been nice, especially in the archive classroom. It was nice to have that in my pocket as I was creating primary source courses, presentations for different history classes, or for general reference for archival collections.

I was able to finagle the administration at Radford into making me the Appalachian Collection Librarian. This also involved working with the curricula which Grace Toney Edwards had begun along with Teresa Burriss, Ricky Cox, and some other folks. I was back in the Appalachian studies mode! Within a couple of years there, an archives position opened up at Radford—that would have been in about 2009— and I moved into that role.

During that time it really turned into an Appalachian collection. There were bits and pieces of regional materials already there and available to pull together. The Virginia Iron, Coal, and Coke Company Records were there. They had been processed by a community college student well before there was anything resembling an archive. It wasn’t a bad job but we cleaned those up, then started actively seeking other collections. Like a lot of Appalachian collections, it started off with one thing that had been dumped there. And then, when that went well and was noticed, the institution asked, “What do we do with this?” There were also oral histories—oral histories were really big in the ’70s and ’80s. We kind of took those components and started to build the Appalachian collections there.

There’s a sort of theory I have that, that once people realize what you’re doing it creates sort of a critical mass. Then people start contacting you about collections. For example, faculty members hear something about “well, there’s this collection, maybe it should come here….” That’s how all of this works, you know? All of that started to happen at Radford around 2010. I was finally an Appalachian archivist!

TM: Are there any collection highlights you are proud of from your time at Radford? Or any interactions that you remember with donors that were important?

GH: Oh yeah! We had a lovely, wonderful faculty member who had become friends with Kenneth Farmer, an elderly photographer in the nearby town of Pulaski, Virginia. He lived in an old farmhouse in downtown Pulaski and had been a professional photographer for like 45-50 years. He had, I would imagine, maybe 40,000 prints and negatives in this non-air conditioned house upstairs in a bedroom. The stuff had been put on the bed and around the bed. It was literally a mountain, it curved down with prints and negatives, and it was 100 degrees up there! (laughs)

The faculty member and I spent an afternoon chatting with Mr. Farmer. And he’s like, “Well, I really liked the idea of Radford, but you’re going to need to talk to my kids. They’re academics up in Michigan.” This was all part of the slow process of meeting the people, of gaining their trust. We let them know how the collection would be preserved, explained to them the nature of a donor agreement, and kind of eliminated the potential risk or dangers that they might see in donating this collection.

By the time I left to come to UNC Asheville in 2013, the library director at the time, Steve Helm, was very much a part of this process. One of the last things I did before I left Radford was got Steve together with this faculty member to develop the plan to continue working with the donor. They eventually got that collection.

So, that said, donor relations are not always, “Hey, I’ve got stuff here.” It is more like “Let’s talk and we’ll see if maybe this might work.” For me, that started there, that patience, listening, and being extremely respectful throughout the long donation process.

Sometimes, donors want things that you can’t deliver and you have to acknowledge that. On the other hand, it also means that sometimes you can really surprise them what with what you can deliver and make them very happy about it. That’s so critical, developing donor relationships. It is not just somebody giving you stuff, it’s developing a relationship—with an individual or a family or a company or organization or a church or whatever—and letting them know that when they give it to you, others will use it. You need to assure them that it will have a legacy that extends long beyond anybody’s lifetime that’s in the room at the time. And that is a process and a conversation that doesn’t always happen quickly.

TM: Was your time at Radford when you started working with Marc Brodsky on further studies of Appalachian regional collections?

GH: Marc was at Virginia Tech and we did a research project together. That study was looking at how the 2008 economic downturn had possibly affected Appalachian collections. We found that, despite the bump and the different fiscal troubles that people came into, everybody was pretty optimistic and felt good about state of Appalachian collections. They weathered the hit, they picked themselves up, and they moved on. I manage one of those collections now that was in that study. There’s a resiliency, you know? If you’re an archivist, it’s not about this week, it’s not about this year, it’s not about this decade, it’s not about this century, it’s about the long haul. So some administrative shenanigans, as long as you’re still there with a staff, you should be able to get through.

Marc is now on the editorial board of The Curator. We remain good friends and catch up with each other quite a bit. (aside) Marc, I’m gonna try to pull you more into The Curator now that you’re retired. (laughs)

TM: When you think of Appalachian archives and building them, this region has often been viewed as a place backward and less-than in comparison to other places. With this in mind, has there ever been a time when you had to convince people that their collections are important enough to be preserved?

GH: Yeah, there has been in fact. For several years now, I’ve been having a conversation with some folks—and I’ll keep this anonymous to protect them—but they’ve got a staggeringly good postcard collection and a lot of small print monographs that come supporting what they’ve got. It’s really, really impressive. They’re good friends of someone who has donated her collection, Elizabeth Kostova, who has Asheville roots and is famous for writing The Historian. Elizabeth connected me with these folks. I spent an afternoon with them, looking at all their collection. The whole time I was trying not to have my jaw drop down to my knees! I kept looking at one really important thing after another and they’re like, “Does this have any value?” They are originally from Florida, but they came here to region, and they got “it.” There’s not any sort of superiority thing about these folks, they understand the importance of the mountains, who has lived here and who still lives here. We’re still working on that conversation.

TM: Are there any best practices you can share with other regional archivists who are beginning the careers?

GH: One thing I find really valuable—probably some archivists don’t like the idea of this—is that I always feel empowered to say: “This doesn’t have to go to us.” You have to be comfortable giving it to another collection, especially if you know that they are in a better location for it or if they have the appropriate resources and will take care of it. Sometimes collections fit better at different places. I’m always open about that. I’m very sincere about that because, early in my career, I witnessed some archivists that were extremely territorial. I thought it was a shame to be that territorial, especially in how it put pressure on donors. It’s a real embarrassment to archivists to have people being predatory about acquiring collections. Any archivist practicing their career that way is missing the point. If you want to do that, go do something like business or another trade. Pardon me! (laughs) The whole point of archival work is letting donors know: “What you’ve got here is important, and it needs to be somewhere where people can use it.”

TM: What was what was it like at UNC Ashville your arrival? What was the state of their Appalachian collections there?

It was deliberately set up in 1977 as the Southern Highlands Research Center. They were looking at different names and decided that the “Appalachian collection” wouldn’t work because it had already been taken by Appalachian State. It was intentionally set up as a specifically urban Appalachian collection, because the two professors who did this were under the perception that all other special collections—this was the 70s and 80s—were just collecting folklore.

It was a time of extreme growth and development and Appalachian Special Collections. Some places were getting their first professionally trained archivist and to run them, and some places were setting up shop for the first time. It was a real big growth area, development area. It’s during that time that Cratis Williams gave a speech at Mars Hill, where he said that every college and university should have an Appalachian collection. Cratis worded it differently, and far more eloquently, than I ever could but it was a clarion call out there. It was in the air and the collection was set up that way.

There were some times where there wasn’t an archivist there. My predecessor, Helen Wykle, had done a really good job of continuing to collect Appalachia. She got a lot of really important collections. A standout urban collection is the Housing Authority of the City of Asheville records, which document one of the most extensive per capita urban renewal projects in the country. That collection is in use now. There are reparations issues going on in Asheville and that is part of the documentation they’re using with that.

Helen was here for 17 years and I’ve been here for 11 years. So, for the last three decades, it has had a very strong Appalachian focus. We define ourselves as an Appalachian collection.

TM: Are there any collections you are proud to have added to the legacy of regional collections at UNCA?

GH: Well, there had been pretty well established community connections before I got there. There was a strong connection with the Jewish community in Asheville, which continues. Sharon Farher, a very good local historian who works with the Jewish community, opened up a lot of doors and brought in some collections. When the collection started in 1977, there was a focus on showcasing more diversity of Appalachia and that has continued to be important. Since I’ve been at UNCA, I’ve almost doubled the size of the space.

Kathy Newfont is one example of a scholar who helped us build, she had been in to look at a couple of our smaller environmental collections. These were collections on environmental groups, one that came to mind was the Citizens Against Clearcutting the Asheville Watershed collection. Through this she connected us with a really wonderful, local environmental activist. He gave us several collections of records from different environmental groups he had worked with, he got us in touch with MountainTrue, which is a very strong advocate for environmental issues in western North Carolina. When we got the MountainTrue papers, a colleague of mine who had been volunteering with RiverLink said, “Well, it sounds like you might want to be home for RiverLink, too!” So, now we have RiverLink papers! With those and others, we have a really strong set of environmental advocacy collections. It’s that critical mass theory, that once you start getting collections in one particular subfield, more can come in. So we now have really strong environmental activism environmental group. It’s not always activism, it’s more like awareness, you know, everything that goes with folks like this. We’ve built a strong set of those collections.

One colleague that I’m really proud of working with is Darin Waters, who was at UNC Asheville and is now the head person in the Department of Cultural Resources at the state. Darin donated his grandfather’s collection, the Isaiah Rice collection, to us. To the best of my knowledge, it is the largest collection of photos of an African American Appalachian community taken by a member of that community who was considered an insider. They’re very candid, I mean, Rice carried a camera with him everywhere. We have 1400 images that came from that. They’re really quite extraordinary!

In terms of slowly getting to know a donor and building trust, Dan Pierce, the Appalachian historian at UNC Asheville who is just retiring this year, introduced me to some friends of his, Bill and Alice Hart. Bill and Alice are from western North Carolina, their family roots go back multiple generations. They had decided they really want to know everything they could about the region. They, very intentionally, built a library of specific topics. They got every catalog George Brosi ever put out when they were in print and they were contacting rare book dealers. Bill would see something in a footnote that he thought was good, they find it they’d find rare copies of stuff. They ended up building a private library.

My partner, Barrie, and I became friends with them. When we would go out there, Bill would always pull books off the shelf and just give this little master class about a particular book. An example is The Cherokee Physician, published in the 1840s in Asheville, Bill would know so much about that. Based upon that trust, they donated their entire library to UNC Asheville. We completely rearranged and cleared out our reading room to shelve it. One half of our reading now room now holds the Bill and Alice Hart Collection. Additionally, having gained that trust, Bill then gave us his staggering ephemeral collection, which we’re processing right now.

Those are those are some of my favorites. There’s others, too! I’m leaving some out. I added it up and I’ve added somewhere over 60 collections in 10 years.

TM: For those starting out with an idea towards working in Appalachian archives, how would you say a background in Appalachian Studies has benefited your work?

GH: Well, let me also say this, in the job description for my job one of the requirements is a knowledge of Appalachian or western North Carolina history. I mean, they wanted somebody who knew Appalachia.

You have two complimentary things, from my perspective. You have to have the knowledge of archiving: you have to have the skill set, you have to understand the processes such as preservation and conservation and description, and, it could be argued, that any well trained archivist could come into an Appalachian collection and do fine. That would probably be the case to a large extent, but when you get more than nuance is when you start making collection development decisions: when you’re talking to donors or when you’re seeing something that comes in with an Appalachian focus.

This may be, for example, understanding that this is documenting the African American community that hasn’t been documented before, or that this particular group now is documenting the early emergence of an LGBTQ community—the things that we see in Appalachian studies as important. To a non-Appalachian Studies eye, it may look like, “Oh, that’s small collection, we don’t need to get that” because it might be, you know, half a linear foot of documents, or less than that That’s where the knowledge of Appalachian history and culture is essential—the broad, extremely wide range of disciplines that we study and the ability to take a look at a potential collection to go: “Does this have value?” The more you’re steeped in that as a subject specialist, the more you’re going to be able to make a good decision. Then, on top of the regular skill set, you’re going to be able to describe it, to understand what’s in the collection, and how it should be represented in the finding aid. Knowing how a collection can accurately portray the region and putting that in your description may be invaluable for somebody who may not pick up on that nuance immediately.

TM: With that in mind, how has your involvement in the Appalachian Studies Association helped to spread the word about Appalachian competencies in archives?

GH: Well, I proposed a committee of Appalachian archivists to the ASA Steering Committee and gullible people believed it was a good idea! (laughs) When I pitched it, Kathy Newfont was the president of ASA, and I was talking about it as an idea to her when she was doing research. She was very supportive! So, the first thing I did was reach out to a bunch of other Appalachian archivists, and say, “Hey! Do you think this is a good idea? Would you support it?” It was unanimous, everybody said, “Absolutely!” Since then, it has only grown, and there are a number of non-archivists who are just interested in the process and interested in the importance of it. I think it’s getting the gospel of the importance of Appalachian archives out there and raising awareness.

TM: Out of this process grew The Curator (which we are featured in now!). How would say the response has been to that publication that still spreads the gospel of Appalachian archives?

GH: Our readership is pretty high! It’s on a WordPress platform at UNCA and will remain there after I retire. There are hundreds and hundreds of readers, initially, for each issue and more join in read later on. I’ve had a couple of people contact me from way outside the region, who had read about a collection are something in The Curator and contacted us about it! So, I know that a tiny, tiny anecdotal level, that it is making people aware who would not have been otherwise aware of specific collections

TM: Who would you say were your mentors in this work?

GH: Fred Hay was clearly a mentor. He’s the most Appalachian of my archivist mentors. Dean Covington at Lyon College was my first library mentor. I didn’t have formal archival training in library school even though I wrote my thesis on archives. So I went to Rare Books School and took several courses in archives and special collections. Jackie Dooley and Bill Landis’s class at Rare Books School was very important in helping me to get my feet wet.

A lot of it’s been the scholars I’ve worked with, too. At UNC Asheville, scholars such as Erica Abrams Locklear and Dan Pierce. These are not so much mentors, but people who have been aware of Special Collections and seen them as the valuable resource they are and have promoted their use.

TM: By extension, who have you mentored?

GH: I know I’ve mentored some other people, for better or worse! (laughs) I think you might be in that club…

TM: Most definitely!

GH: My colleague at UNCA, Ashley Whittle, started doing internships with me as a history student. Then I hired her several years ago, and she’ll be running Special Collections at UNCA when I retire this summer. There’s a number of students out there I’ve mentored. Derek Whisnant worked with us for a while. Derek has expressed interest in going into archives, but he’s not ready to go back and doing that yet.

I’ve mentored a handful of other students. We have an internship program where it’s pretty hands on. I’ve been doing this since Radford. We have interns read a book on archival theory and then they apply that theory and process collections. These are usually people who are interested in librarianship or archives as a career. We talk with them about that. Ashley is doing very much what I’ve been doing with that – helping interested people to see if this is a career for them.

TM: What have you seen as far as changes in the importance, the visibility of Appalachian archives in your career?

GH: I’m a chronic optimist! It’s a curse. (laughs) But I think that goes back to the study Marc and I did that showed an underlying sense of the resiliency and the sustainability of Appalachian collections even under hard fiscal times. I think that’s still there. I think that a lot of the people who do this take their job seriously. Everything you’re doing is for is something that’s going to be here, by definition, long after you’re gone. Just the showing up at work and doing your job is about the long run. With that in mind, I tell everybody that works with me that, by the end of the day, every day, there’s going to be more undone in your collection than done. So, you come back the next day. If you’re wanting to get it all done that day, you’re never going to finish.

TM: What do you see is the challenges to the future of Appalachian archives?

GH: I think that the challenges are also the challenges that face the universities, in general. The academy is under attack by people who don’t understand it, who see it as a political thing. With that in mind, it’s important for archives to keep that building of awareness and presence there. Something that comes to mind, an example of how awareness of a problem at a specific institution can be addressed by the larger Appalachian Studies community happened at Radford, when they were seriously considering getting rid of the Appalachian Studies program. There was a letter of support for Radford’s program from ASA and there was a huge outpouring from the ASA community. That made a difference!

TM: What would be your suggestions for those continuing in Appalachian archives? What are the new collecting areas and new ways of collecting that you’re seeing emerging?

GH: One thing I’d suggest for anyone collecting is to make sure you stay up to date with Appalachian Studies—pay attention to what’s going on Appalachian Studies, pay attention to the Appalachian Journal, Journal of Appalachian Studies, read The Curator. There’s been a lot of changes in Appalachian Studies, like any academic thing in America. Appalachia grows and evolves and changes, just be aware of that. Ten years ago, we didn’t have any LGBTQ focus in collections and, now, it’s a major theme that people are recognizing. People are going “Hey! It’s my story” and we have an awareness of that.

There’s also a collection development thing that comes from making connections with your Appalachian Studies faculty. They’re out doing the field work, they know what’s going on and they can identify collections, they can make people aware of your collections. Also, when you get a chance to advocate, you need to do that. All archivists, all archives are doing their own outreach, but if you get a chance to advocate through local news or anything you can do like that, to raise awareness, is going to be positive for your collection. It’s outreach that makes whatever political bumps are going on smaller and the bigger picture will emerge as to why collections are important.

TM: Just for fun, here’s a more personal collection, who is Gene beyond the archives?

GH: I am a photographer and enjoy photography. Much to my surprise, I recently seem to have become a poet of sorts. I had three poems published in the last issue of Appalachian Journal. I didn’t find my poetic voice till about 2017 or 2018, so I’ve been working on that. I have the good fortune of being in a writing group with Thomas Rain Crowe and some other folks and in that group, I found it. Now, I’ve been slowly and steadily writing. When I retire, those are both going to be a major focus, photography and more writing.

I’ve been asked to join a record listening group. So, I’ll be hanging out more with more people listening to more music. And I’m one of those guys who owns a guitar but can play a stereo. Maybe this is the title of this whole piece? (laughs) I’m going to spend a whole lot of time in front of the stereo.

Also, I’m going to read a lot. My backlog of reading is just staggeringly large. I’m doing this yearlong online nature writing course with Janisse Ray, a class on the idea of Place. It’s been really, really good. It’s a lot of readings, and there are some other writing stuff. And so a lot of what I’ve been thinking about in Janisse’s course is going to manifest itself in some ways. Yeah, and spending time with my wife and family and friends, you know, the usual cliche, retirement stuff, right.

Otherwise, I am kind of a shy guy, really. I like hanging out at home. We live on a mountainside outside of Asheville. I live on a hillside that it’s in a suburban neighborhood, but it’s a heavily wooded lot. I have never really been very good at identifying of trees, outside of more than a handful. I’m going to identify and map all the trees in my yard. That’s going to be a project.

I’ve got a couple of writing projects going in addition to poetry. I hope to, within a year or so get at least something ready for a chapbook. I’ve got a couple of essays in the works, things in mind that are related to Appalachian and environmental themes. And I’m going to continue editing The Curator for a while, at least. I feel like I still have a lot to say there. I don’t know. I’m just a guy. (laughs)

TM: Gene, thank you for your time, dedication, and inspiration to all of us who appreciate regional collections. I appreciate you taking them time to sit down and talk about your career and the importance of Appalachian archives. Like you, I think archives are essential to understanding a place and people who have often been misrepresented. The collections you have helped create and continue to promote are part of that and your work has had real and lasting impact on a lot of us in the region and beyond. Are there any other thoughts or reflections you would like to share as we celebrate your career?

GH: It’s important to remember that, when it all comes down to it, this is all about people. It’s all about what people have done. People can come, form collections of organizations and churches and all sorts of stuff but, by in large, it’s individuals doing things and that’s what’s made Appalachia what it is. That’s what we’re documenting and reflecting in the archives. You always keep your compassion in humanity while you’re doing this stuff, because that’s what you’re documenting, sometimes the lack of it in some places (laughs) and the wonderfulness of it in other ways. It’s very much about who we are, whether we’re in-migrants to Appalachia, like I am, or whether we’re from here, like you, who both embrace the region. It’s knowing that it’s important, it’s worth celebrating, understanding, living in and respecting.