This article appeared in the Volume 5, Issue 1 Spring/Summer 2024 issue of the Appalachian Curator. Click here to view a PDF of the full issue.

By Megan Adams, 2023-2024 Kenneth R. Trapp Craft Assistant/Curatorial Fellow, Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts

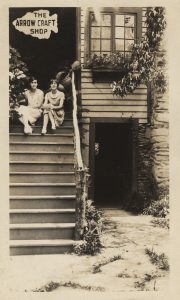

For those who may not be familiar with Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts, Arrowmont is an arts and crafts school in Gatlinburg, TN. The campus is situated on a 13-acre wooded hillside in downtown Gatlinburg at the edge of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Arrowmont has a rich history that pre-dates the incorporation of the town of Gatlinburg. Before Arrowmont became the craft school it is today, the campus was home to the Pi Beta Phi Settlement School which was founded by members of the Pi Beta Phi women’s fraternity as a philanthropic project in 1912.

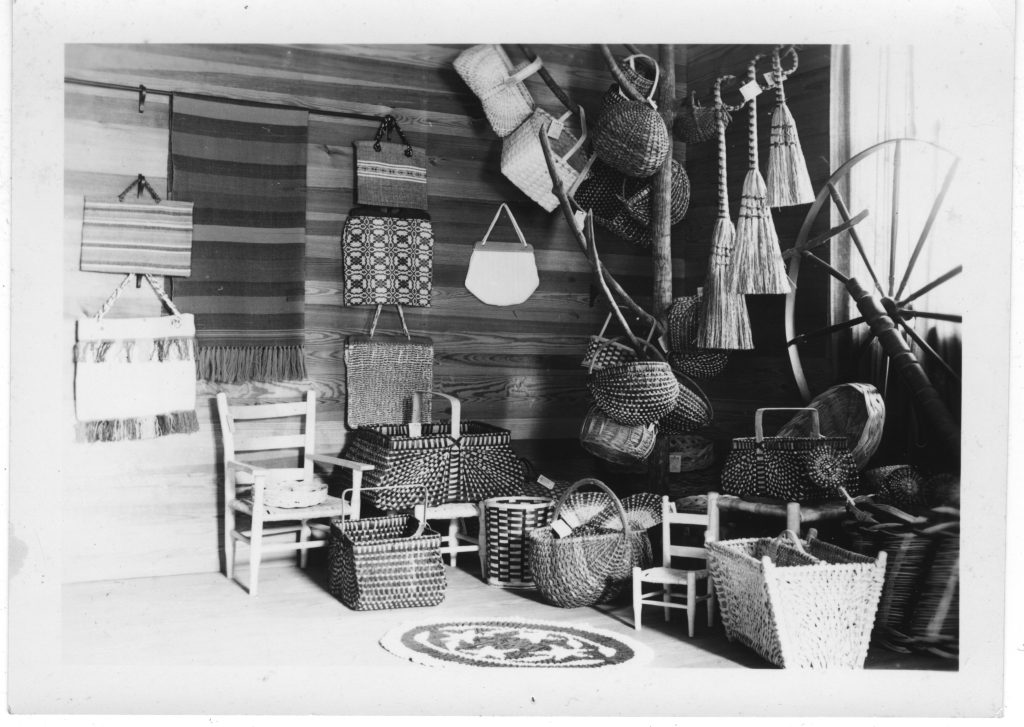

The settlement school brought education and health care to residents, and in turn community members shared with school faculty their traditional Appalachian handicrafts. In 1915 the settlement school began a business selling local handmade goods with the goal of reviving the market for traditional mountain craft. Soon after the inception of the business, the school incorporated art and crafts instruction into their course curriculum, adding classes taught by talented local Appalachian artisans. In 1925 the school brought on a person full-time to run the craft business, and in 1926 the settlement school opened the Arrowcraft store on campus to localize its craft sales.

The Arrowcraft shop and the settlement school grew alongside the Gatlinburg over the next two decades. In 1943 the Sevier County government assumed control of the educational system, and so as the Pi Beta Phis relinquished their educational responsibilities, they decided to further pursue their craft endeavors in the area by partnering with the University of Tennessee in Knoxville to hold its first summer craft workshops on campus in 1945.

Due to the success of the summer workshops, after Phi Beta Phi was finally finished assisting the Sevier County government with the transition of the oversight of the education system in 1965, the grounds and buildings of the settlement school became Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts.

Though Arrowmont has been an arts and crafts school since 1945, it wasn’t until 1970 when Arrowmont opened the Emma Harper Turner Building, that the organization was able to start collecting art and shaping a permanent collection. Over the last five and a half decades, the collection has grown incrementally. Today Arrowmont’s permanent collection contains around 1,000 artworks in a range of media including ceramics, wood, fiber, weaving, basketry, paper, printmaking, photography, drawing, painting, enamel, glass, metals, and mixed media. Arrowmont’s art collecting impetus is two-pronged. Arrowmont (1) collects objects related to its history, including its settlement school origins, and it (2) collects artwork by Arrowmont affiliated artists including but not limited to instructors, former artists-in-residence, and prize-winning artists from its biennial and national exhibitions. The artworks in the permanent collection are a visual representation of the craft school’s past, present, and future and are an invaluable resource for the study and appreciation of the history and contemporary practice of art and craft locally, nationally, and internationally.

In addition to the permanent art collection on campus, Arrowmont has an archive and special collections of historic significance that includes The Rossetter Collection. The school is working towards cataloguing and re-housing its special collections and archives with the goal of making them more accessible to guests and the public. Some work in this area has already been done thanks to a collaboration between Arrowmont, Pi Beta Phi Elementary School, and the University of Tennessee in Knoxville on an IMLS grant funded project in 2002. Through this project, a substantial amount of Arrowmont’s archival material was digitized by UT Knoxville and is searchable through the university’s digital collections database.

Arrowmont visitors and guests will find that Arrowmont’s permanent collection and archives are accessible on campus in several ways. There is a historic timeline illustrated by photographs from the archives and artworks from the permanent collection displayed in the Arrowmont History Exhibit, which is a permanent exhibition located in the Turner building. There are several large-scale works installed throughout Turner as well as smaller groupings of artworks on view in display cases that are installed in some of the studios. Works from the permanent collection are often utilized in rotating exhibitions around campus and a selection of artworks in the collection is featured every year in the annual permanent collections show curated by the Arrowmont Trapp Fellow.

In 2022, Arrowmont began the Kenneth R. Trapp Craft Assistant/Curatorial Fellowship, an 11-month residential fellowship awarded each year to an early career curator, arts researcher, or art historian. Through the creation of this curatorial fellowship Arrowmont intends to extend their support of artists and craftspersons to include those whose careers support artists and their work. A highlight of this fellowship is surely the opportunity it presents for the Fellow to curate a show using artwork from the permanent collection.

This year as the 2023-2024 Trapp Fellow at Arrowmont, I curated a show titled Crafting a Collection: The Art Collections of Artist-Collectors Nellie Bergh, Jerry Drown, and Bill Griffith. This exhibition showcased three art collections donated by artist-collectors that are a part of Arrowmont’s permanent collection, including the Nellie Bergh Collection, the Jerry Drown Woodturning Collection, and the Bill Griffith Ceramic Study Collection. Each of these collections contains pieces by the artist who donated the collection and artworks from other artists whose works they collected. By taking a close look at the collected artworks alongside the artworks by the artists who compiled each collection, this exhibition explored the ways in which the roles of artist and art collector are interconnected and inform one another, emphasizing the model of the artist-collector as a core part of artmaking and art education that is especially prevalent in the context of Arrowmont as an arts and crafts school.

In ideating a concept for my exhibition, I found it to be very helpful that several of my initial fellowship projects provided opportunities for me to familiarize myself with Arrowmont’s permanent collection. One project in particular inspired the exhibition Crafting a Collection: The Art Collections of Artist-Collectors Nellie Bergh, Jerry Drown, and Bill Griffith. While organizing a part of our permanent collection in collections storage, my colleague and I came across two boxes containing embroideries and other fiber works. I took charge of cataloguing the collection and began researching each artwork. I learned that the artworks in the two boxes were a part of a collection donated to Arrowmont by the estate of fiber artist Nellie Bergh in 1996.

The Nellie Bergh Collection compiled by fiber artist Nellie Bergh contains numerous examples of fiber arts from female artists active in the 20th century including Bergh herself. The Nellie Bergh Collection at Arrowmont is only a subset of Nellie Bergh’s much larger personal art collection. The subset of her collection at Arrowmont contains 30 artworks in total, 10 by Nellie Bergh, and 20 by other artists whose work Bergh collected. I used the inventory sheet and the information I found on tags attached to the back of several of the artworks as jumping off points for my more in-depth research into the works in the collection. What I found was that each artwork in this collection had an important story to tell, and that together the artworks paint a picture of an accomplished artist who was also an avid art collector.

Many major art institutions, researchers, and art historians have taken to investigating artists-as-collectors. While researching the Nellie Bergh Collection I recalled a quote from modern artist and collector Louise Nevelson who stated that “artists are born collectors.” Many notable art world figures make art and amass their own art collections. Investigating the relationship between what artists make and what they collect has contributed to a more comprehensive understanding of who artists are, what they value, and where they find inspiration. Art collections compiled by artists are another form of their creative expression that is not often separate from their artmaking practice.

During my time at Arrowmont, I have seen how art collecting is an integral part of the arts and craft school ecosystem. As an arts organization Arrowmont’s dedication to supporting artists and craftspeople through collecting is manifold. In addition to collecting artwork from Arrowmont affiliated artists for its permanent collection, Arrowmont continues its historic dedication to supporting contemporary arts and crafts practitioners through its commercial ventures associated with its gallery exhibitions and the featured artwork for sale in the Showcase Gallery on campus in the Arrowmont store and in Knoxville at the Arrowmont Gallery. And then there are more informal Arrowmont-promoted avenues of art collecting like the infamous and highly anticipated Pentaculum raffle or the artist-to-artist artwork trades that often happen during the national workshop season.

After discovering the Nellie Bergh Collection, I was excited to learn of two other examples- one historic and one contemporary- of art collections within Arrowmont’s permanent collection that were compiled by artists who were also art collectors. These collections are the Jerry Drown Woodturning Collection and the Bill Griffith Ceramic Study Collection. Intrigued by the synchronicity amongst these three important examples of collections that illustrate the same phenomena, I decided to curate a show featuring the three collections in hopes of learning more about the interplay between each artist-collectors’ concurrent practices of making and collecting art, and the significance of this model of art collecting within the context of our arts and crafts school.

As a jumping off point for my research for this exhibition, I devised a guiding set of questions to apply to each artist-collector. My questions included…

- Who is the artist? What do they make?

- How did each artist get started in collecting art?

- What were some of the guiding principles of their collecting practice?

- How did the artists live with the works in their collections?

- What is the relationship between the artist’s own artwork and the artwork they collected?

- What is each artist’s affiliation or connection to Arrowmont? How did the artist’s collection come into Arrowmont’s permanent collection and when?

- Why did the artists choose an arts and craft school as the permanent home for their collections?

I found some of the answers to these questions through in-depth research online and by consulting physical resources including books, magazines, newspaper articles, exhibition and collection files, old photographic slides, and other archival material. Some answers I found by closely investigating the artworks themselves as well as looking at the collections in their entirety to determine patterns and draw connections between artworks. My resulting exhibition narrative was shaped by the answers I found to the questions I posed.

I organized Crafting a Collection into three distinct sections, one for each collection. In each section I use a selection of artworks from each collection to (1) tell the story of that collection, how it started, how it evolved over time, and how it found its way to Arrowmont and (2) tell the story of the artist-collector who compiled the collection through an investigation of the artworks they made and collected from other artists. In addition to the artwork on view, each section offered opportunities for viewers to go beyond a visual engagement with the art and dive further into the stories embedded in these collections through reading the provided interpretative material, watching the multimedia slideshows, and in the Nellie Bergh section experiencing an immersive reading room where visitors could sit and view a slideshow, flip through copies of Bergh’s original NSC Correspondence course, and use transparency keys to decipher the types of embroidery stitches featured in Bergh’s embroidery samples from her correspondence course. The exhibition began with the Jerry Drown Woodturning Collection.

In 1997 The Jerry Drown Woodturning Collection entered the Arrowmont permanent collection along with a generous donation of funds from Louise and Jerry Drown that were used to help build new wood studios and a dedicated woodturning gallery at Arrowmont. The Drown collection includes 55 wood turned objects, 6 by Drown himself, and 49 from an array of well-known wood turners from the US and abroad, many of whom have taught and/or taken classes at Arrowmont. On view in Crafting a Collection is substantial subset of the Jerry Drown Woodturning Collection.

Jerry Drown was born in Washington D.C. and spent most of his life doing photography work. Drown began his photography career covering Capitol Hill for the Harrison-Ewig News Service. Later, while living in Nashville, TN he worked for the Methodist Publishing House and the National Tennessean. He subsequently made a name for himself through a commercial photography business he opened in Atlanta where he produced advertisements for clients such as Coca Cola, Southern Bell, and Southern Living magazine.

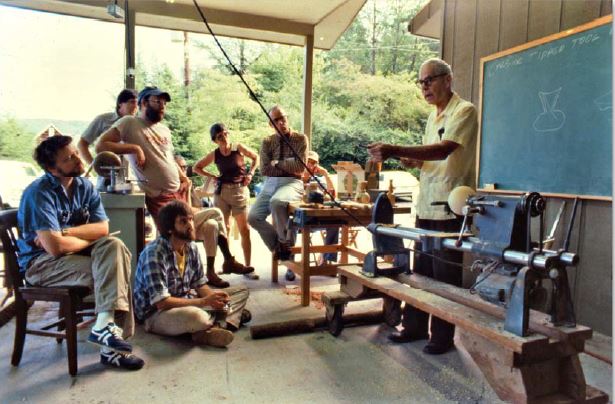

After Drown moved to Gatlinburg, TN in 1986, he became a staple of the Arrowmont community, frequently attending woodturning workshops and events. It was in part due to his prolonged relationship with Arrowmont and his proximity to campus that he was able to build such a robust personal collection of wood turned artwork. Drown developed relationships with many well-known woodturners that he admired and was inspired by at Arrowmont. As the birthplace of what is today the American Association of Woodturners, Drown was a part of the Arrowmont community during a period when Arrowmont was supporting the national and international development of woodturners in ways that no other organization was at the time.

From offering its first woodturning workshops in 1981 to hosting its first national conference on woodturning in 1985, to growing its programmatic offerings through building a new building dedicated to woodturning in 1997, Arrowmont was and has continued to be a hub for woodturners dedicated to the study and practice of woodturning as a craft and a revered art form. The artworks from the Jerry Drown Woodturning Collection on view in Crafting a Collection illustrate some of the important connections Drown made with other members of the Arrowmont woodturning community, many of whom have made major contributions to the contemporary woodturning movement.

One such figure is Rude Osolnik whose artworks in the Jerry Drown Woodturning Collection were exhibited on the back wall of the atrium. Drown’s collection contains 7 works by Osolnik, making Osolnik one of the most represented artists in his collection, second only to Alan Stirt, from whom Drown collected 9 works for his collection. Drown and Osolnik seem to have shared a taste for strong forms with minimal but tasteful decorative ornamentation. From Natural Edge Plate made of redwood lace burl to Laminated Bowl made of birch plywood, the subset of works in Drown’s collection from Osolnik represent the artist’s woodturning mastery in arrange of forms and media. The five works on view in the show offer a glimpse into the range of the Osolnik oeuvre.

The many instances within the Jerry Drown woodturning collection of Drown having collected more than one work by a single artist, to me suggests Drown had an interest in the range of style, forms, and media exploration in each artist’s body of work. Drown collected two or more artworks from several woodturners represented in his collection, and I included many of these works displayed in multiples in the show to demonstrate the way Drown often invested in more than one piece by an artist. In looking at the wood turned objects that Drown made alongside the artworks from other woodturners in his collection one can perhaps begin to see the inspiration he found for his own work in the artworks he collected from his fellow woodturners and former instructors.

Ultimately, Drown was dedicated to “supporting people who are trying to find themselves through working with their hands,” and he saw the donation of his personal collection to Arrowmont as his living legacy.[3] He wanted to give back to the organization that he felt instilled artists and craft practitioners with a sense of self-esteem and self-worth. The Jerry Drown Woodturning Collection is an invaluable repository of woodturned objects that captures an important part of Arrowmont’s craft school history, exemplifies significant facets of the rise of artistic woodturning in the US, and will forever tell the story of artist-collector Jerry Drown, whose life was shaped by his time at Arrowmont and his passion for woodturning.

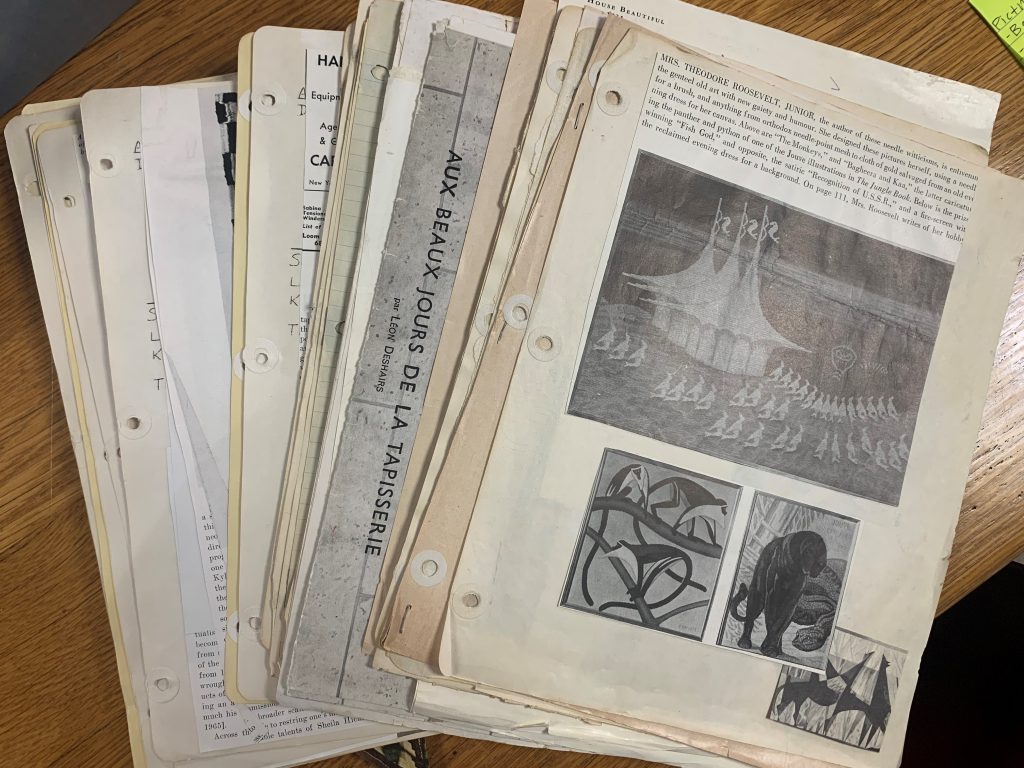

As they entered the collection at nearly the same time, the next section in Crafting a Collection is the Nellie Bergh Collection. Nellie Bergh was a naturalist, needle artist, teacher, and textile collector. She grew up amongst a family of sewers and quilters in Ohio. She studied art and home economics at Ohio University, New York University, and Columbia Teachers College. Bergh taught clothing construction and clothing design history for eight years at Skidmore College, Columbia Teachers College, and the Pratt Institute. One of the most remarkable facts that I uncovered in my research into Nellie Bergh is that it wasn’t until her 50th birthday that Bergh began her foray into embroidery. Bergh was a self-taught embroiderer. She was a connoisseur of technique and design, studying all the available books, magazines, and literature she could find on embroidery. If you spend some time in the textile and fiber arts section of Arrowmont’s Marion G. Heard Resource Center, you will find many books about embroidery that were donated by Bergh to Arrowmont along with her donation of art.

As you can see from the content of a scrapbook she compiled, pictured above, she was constantly collecting information related to the practice of embroidery from newspaper clippings, magazine articles, old photographs, and exhibition materials.

Bergh’s self-education and her previous experiences as a teacher and naturalist come together in her work- she produced designs inspired by nature, adopting a creative approach to translating her impressions of the natural world.

In artworks such as Club Moss and Tulip Petal, Bergh invites viewers to join her in an act of close looking, considering the natural subject matter from a new perspective. Bergh celebrates the intricate beauty of natural forms in these embroideries through the attention she paid to rendering each and every detail. Her passion for nature clearly played an important role in what embroideries Bergh collected from other artists. Like Jerry Drown, it is evident that the artworks by other artists in Bergh’s personal collection inspired her own work. One clear example is a pairing I put together of Bergh’s Tapestry Tree and Barbara Remington’s Untitled fiber work of the same subject.

The influence of all things nature inspired not only what Bergh made and collected, but it also inspired Bergh in her sustainable method of mounting and framing her embroideries for display.

These stunning examples of Bergh’s pulled thread embroidery were framed by Bergh and her husband Philip using slats made of driftwood that they foraged from Little Neck Bay, Long Island where the couple lived for many years. This type of framing became a signature method for displaying her pulled thread embroideries that added a natural, site-specific flare to her work. She used the specially designed frames by counting threads of the background fabric and scrupulously finishing the edges of the fabric with picot stitches.

Bergh’s veracity for making and learning within the discipline of embroidery were matched only by her dedication to teaching embroidery. She taught embroidery privately and in adult education systems, and she and her husband traveled nationally and internationally giving slide lectures to different groups.

In the late 1960s she created an Embroidery Correspondence Course for the National Standards Council of American Embroiderers. Copies of the original correspondence course Bergh developed from the Arrowmont archives were available for perusing in the Bergh reading room as were many of the original samplers from her correspondence course. With the reading room I aimed to immerse visitors in this beautiful, hand-crafted resource.

Nellie Bergh was a difficult figure to research, as there is not much information out there about her. I am happy to have been able to piece together many facets of her story using both the artwork and the Bergh-related material I found in our library and archives. Though the detailed backstory of Bergh’s relationship with Arrowmont has yet to be uncovered it is clear to me that she revered the work being done at Arrowmont to support and educate artists and craftspeople locally, nationally, and internationally. Our mission and that of Bergh herself are very much aligned, which makes Bergh’s donation of a part of her personal collection to Arrowmont a sensical choice for an artist-collector hoping to preserve the legacy of her art collection as a source of artistic inspiration and a resource for the study of embroidery and fiber arts.

Last but certainly not least, is the final section of the exhibition dedicated to the Bill Griffith Ceramic Study Collection. This collection was a special collection for me to work with because I got to know Bill personally and worked closely with him over the course of my fellowship. As the only living artist-collector whose collection is featured in Crafting a Collection, it was so special to be able to conduct research in a different way. I learned about Griffith and his collection through conversations and visits to his home and studio. Bill Griffith is a ceramic artist, educator, and former Arrowmont arts administrator from South Bend, IN. He holds a bachelor’s degree in art education from Indiana State University and a master’s degree in art education with a concentration in ceramics from Miami University. His functional and

sculptural ceramics continue to be exhibited and published, and he has artworks in a number of private and public collections. Over the years Griffith has developed an impressive ceramic collection that contains a variety of types of objects acquired from friends, colleagues, and artists he admires from the US and abroad. His collection represents a range of ceramic styles and techniques from historic to contemporary. Griffith is drawn to objects that tell stories, represent memories, and connect him to his community. He describes his collecting impetus as being emotional, aesthetic, and interpersonal. The Bill Griffith Ceramic Study Collection contains over two hundred artworks by notable ceramic artists, including several works by Griffith.

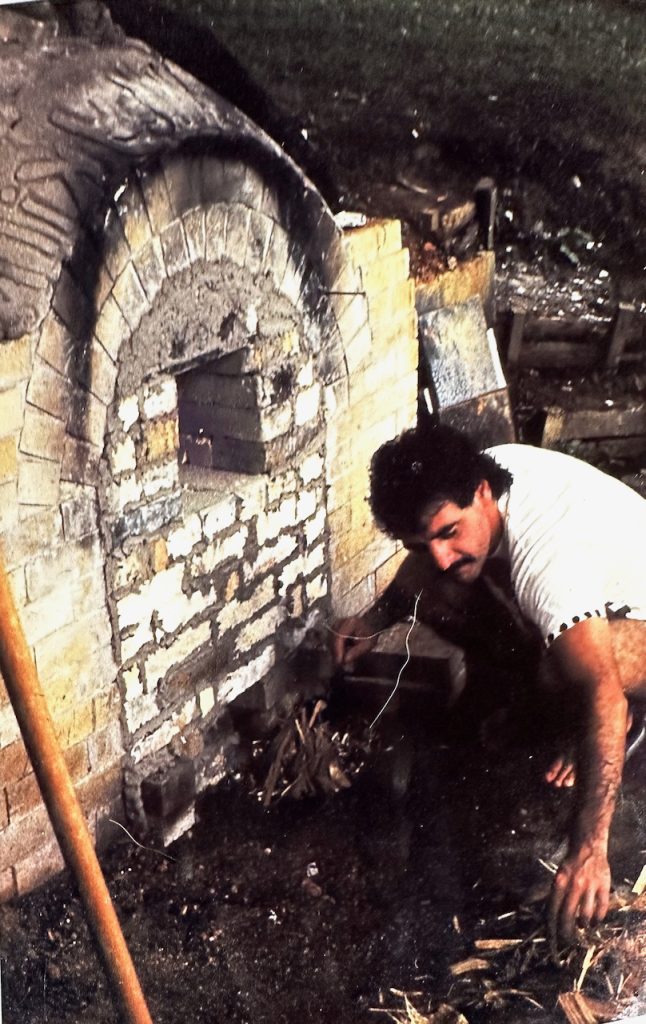

Griffith first came to Arrowmont as a work-study student in the early 1980s. The Platter on view in his section of the exhibition is a piece that Griffith made at Arrowmont in 1984 as a studio assistant. The piece was fired for three days in Arrowmont’s anagama kiln. Another piece of Bill’s from 1997 is Basin, which was also fired on campus at Arrowmont in the Anagama kiln. The third piece on view from Bill is Dwelling that he made in 2017. This work is a part of a series titled Dwellings. The pieces in this series reference ancient architecture from the Native American Anasazi, Japanese Haniwa, and Mayan and Incan peoples. Griffith attributes the intrigue of the sculptures to “the beauty and strength of the exterior arch form juxtaposed with the mystery and intrigue of the protected quiet interior spaces.”[2] The tensions of interior vs. exterior, the feeling of being protected from the world vs. being exposed to it have a sort of universal resonance, as Griffith poetically summarizes “the work reflects the inward sense of need for dwelling space we all have within us.” [2]

In 1987, Griffith became the Assistant Director at Arrowmont, where he worked for nearly three and a half decades before he retired in 2021. During his 34 years working at Arrowmont, Griffith started many programs that have made the organization what it is today. One such program was the Utilitarian Clay National Symposium that he launched in 1992. A grouping of works in Crafting a Collection represent the ceramics that Griffith collected from artists participating in the UC symposium over the years from well-known ceramicists Derek Au, Michael Simon, and Sunshine Cobb.

Another important program that Giffith helped start at Arrowmont was the Artists-in-residence program that started in 1991. Over the years Griffith formed close personal and professional relationships with the many talented artists that came to Arrowmont annually for 11-month residencies. Featured in his section are many artworks that Bill acquired from Arrowmont AIRs.

This subset of Griffith’s ceramic collection features sculptural ceramic works, many like Thaddeus Erdahl’s Private Dazzle and Richard James’ The Water Carrier are quite large in scale. These sculptural ceramics illustrate Giffith’s eye for work representative of the contemporary innovations happening in the field. Many of these artists use traditional ceramic processes and techniques to achieve their sculptural works that represent the contemporary innovations that these young artists have brought and are bringing to the field of ceramic arts.

Another key aspect of Griffith’s life that informed the artworks represented in his collection as well as the artworks he makes, are his travels abroad. On view in Crafting a Collection were some of the artworks that Griffith purchased from ceramic artists in Japan, Peru, Ecuador, and Mexico. Like Jerry Drown and Nellie Bergh, Griffith is a dedicated life-long learner and educator, and on his travels, he sought out opportunities to meet with local arts from each country to learn about them and their approach to their ceramic craft. The impact of this sort of relationship building and cultural exchange clearly had a huge impact on Griffith’s life and practice.

When Bill talked to me about artists such as Ecuadorian artist Esthela Dagua, who made the Kichwa Vessel and Kichwa Clay Figures on view in Crafting a Collection he lit up, clearly warmed by the memory of a meaningful visit with an artist who was carrying on the culturally significant and ancient Kichwa pottery tradition.

In the exhibition I curated several walls that each offered an exploration into a single functional form represented in Griffith’s collection- there was a wall dedicated to teapots, one to pitchers, and another to cups, mugs, and tumblers. In both his own ceramic practice and in his ceramic collecting, Griffith centers form, function, and beauty.

If you are lucky enough to be invited to visit Griffith’s home for a studio visit, dinner, or a conversation over a cup of tea you will get to see the very special way that Griffith lives with his collection, leaning into the functionality of his collected works. Griffith is known to give lively demonstrations to visiting classes who get to witness Griffith pour water out of pitchers and teapots from his collection, and when you sit down to dinner or tea at his table you are tasked with selecting your own plate, bowl, and drinking vessel from his collection to use for the occasion. When this collection is officially accessioned into Arrowmont’s permanent collection, the collection will continue to be activated by functional and educational engagement.

The Bill Griffith Ceramic Study Collection is in the process of being donated to Arrowmont by Griffith. A dedicated exhibition and study area is being outfitted on Arrowmont’s campus in the West complex to display and store Griffith’s collection supporting the intended function of the collection to serve as an educational resource for Arrowmont instructors, students, staff, and visiting researchers. Arrowmont is fortunate to be able to continue to grow its permanent collection through the acquisition of another important art collection that has been carefully and lovingly crafted by an artist-collector.

Although the art collections of each artist-collector included in Crafting a Collection reflect the artist’s own taste, style, and personal collecting habits, the three collectors share important commonalities that enhance our understanding of the critical mutuality of artmaking and art collecting within the art and craft school context. Nellie Bergh, Jerry Drown, and Bill Griffith were and are all connoisseurs of their respective disciplines, each amassing impressive collections within the discipline they themselves practiced. They share a dedication to perfecting their craft using their collections to gain knowledge of the technique, process, and style employed by the notable artists they collected. And the impressive index of collected artists represented in each collection reveals the networks of relationships that the artist-collectors formed via teaching, attending workshops and professional events, traveling, and working. With the donation of their art collections to Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts, Bergh, Drown, and Griffith share the wealth of knowledge and inspiration contained in their collections with us.

I am honored to have been able to bring the stories of these artist-collectors to life through my curation of Crafting a Collection: The Art Collections of Artist-Collectors Nellie Bergh, Jerry Drown, and Bill Griffith. This show is a celebration of the invaluable artistic, cultural, and historic resources at Arrowmont, and is a testament to the legacy and impact of the organization as an important Appalachian art and craft institution that enriches people’s lives through art and craft.

Megan Adams is an art historian, curator, writer, and community-engaged scholar from Denver, CO. She holds a BA in English from Oklahoma State University and an MA in Art History and Museum Studies from the University of Denver. Adams adopts interdisciplinary approaches to art scholarship and is passionate about studying the relationships between humans and the environment articulated in art throughout time, with a special emphasis on contemporary ecological and environmental art.

For more information about programming, galleries, or collections at Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts, please visit our website. More information about the Kenneth R. Trapp Craft Assistant/Curatorial Fellowship can be found on the website here. Inquiries regarding galleries or collections at Arrowmont can be directed to Galleries & Collection Manager Heather F. Wetzel at hwetzel@arrowmont.org.

Bibliography

[1] Griffith, Bill. “Clay Culture: Collecting Stories.” Ceramics Monthly, October 2014, pp. 20-21.

[2] Griffith, Bill. “Sculpture.” Bill Griffith Clay, https://billgriffithclay.com/section/265521-Sculpture.html.

[3] Morrow, Terry. “Cover Story: New studio carving out opportunities.” The Mountain Press, March 7, 1997, pp. 1B-2B.

[4] Raulston, Karen McBee. “Nellie Bergh- Her Embroideries and Her Collections.” Needle Arts, vol. xv, no. 3, Summer 1984, pp. 10-13.

[5] Rettig, Dixie O. “Nellie Bergh Collection Donated to the Council.” December 13, 1996, pp. 2.