This article appeared in the Volume 2, Issue 2 Fall 2020 issue of the Appalachian Curator. Click here to view a PDF of the full issue.

By Ethan Mannon and Karen Paar, Mars Hill University

During the fall 2019 semester at Mars Hill University, work began on a project made possible by a “Humanities Research for the Public Good” grant from the Council of Independent Colleges. The project—“Influence and Legacy: The Farmers Federation in Madison County, North Carolina”—started with research in the James G.K. McClure, Jr. Collection housed in the Southern Appalachian Archives at Mars Hill University.

The McClure Collection includes many of the records, publications, and photographs that the Farmers Federation created during its decades of operation. The Federation began in 1920 with a cooperative business model intended to help farmers in the Fairview, North Carolina area purchase supplies and market crops in a way that brought them profit. The organization quickly expanded throughout western North Carolina and ultimately touched all aspects of farm life—not just the growing and selling of crops and livestock, but also education, religion, and alternative sources of income such as marketing forest products and selling handmade crafts.

The primary goal of the “Influence and Legacy” project was to make this archival material more visible and accessible by creating a virtual tour of a representative western North Carolina farm. The researchers were also hoping to answer a straightforward research question: what kinds of crops, crop varieties, and farming practices did the Farmers Federation encourage during the first half of the twentieth century? Entering into the project, the researchers hypothesized that the Federation encouraged farmers to adopt high-yielding varieties, and that the Federation’s influence decreased the diversity of field and garden crops in the region.

The Research Team and Their Work

The “Influence and Legacy” project involved a collaboration between the Appalachian Barn Alliance (ABA) and Mars Hill University. The Appalachian Barn Alliance is an organization based in Madison County, North Carolina that seeks to preserve the area’s rural heritage “through the documentation of the historical barn building traditions and the barns they represent.” The MHU research team was made up of three members: Michaela Lambert (a Business Administration major and English minor), Archivist Dr. Karen Paar, and Dr. Ethan Mannon (Associate Professor of English). They were joined by ABA members Mike Foster and Gail Meadows. Throughout the fall 2019 semester this team combed through the three largest categories of the McClure Collection. The Collection includes over 3,000 black and white photographs, several boxes of McClure’s personal papers, and hundreds of issues of the Farmers Federation News—a monthly newsletter that included articles on farming and forestry practices, details about Federation events and activities, and advertisements.

ABA member Taylor Barnhill consulted with the MHU team to help imagine and plan the virtual tour. He also showed Michaela and Ethan some of the farms in Madison County where buildings from the era of the Federation still stand.

Archivist Karen Paar finished arranging and describing the McClure Collection by rethinking its arrangement, then reworking a draft of a finding aid that had long been the best access point to the collection’s materials. The James G.K. McClure, Jr. Collection finding aid is now shared on the Southern Appalachian Archives website as well as the Mars Hill University Library’s LibGuide for the Southern Appalachian Archives. Paar has also begun to share digitized photographs from the McClure Collection on the Southern Appalachian Archives website. Additional photographs from the McClure Collection will be added over time.

The Research Outcomes

The research conducted for the “Influence and Legacy” project yielded three outcomes: a virtual tour of a representative western North Carolina farm, a set of exhibit panels describing farm life and the Federation’s work in western North Carolina, and a formal presentation on the team’s research findings.

1) The Virtual Tour

The spring 2020 semester got off to a promising start for the research team. Dr. Mannon and Ms. Lambert continued their research in the archives and also began planning and developing the virtual tour. COVID-19 stalled their progress. MHU, like most other colleges and universities, closed the campus in March and moved all instruction online.

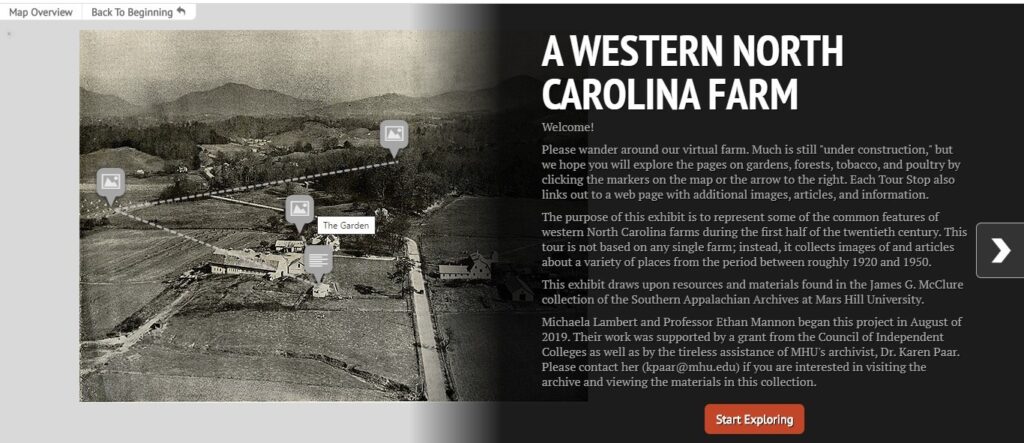

Despite this disruption, the MHU team managed to create a pared back version of the virtual tour. Using the “StoryMap” application provided free by Northwestern University’s Knight Lab, they created a brief farm tour with four of the features one might expect to find on a typical western North Carolina farm between the years of 1920 and 1950: The Garden; A Farm’s Forests; Tobacco: Field, Barn, and Market; and a Chicken Coop.

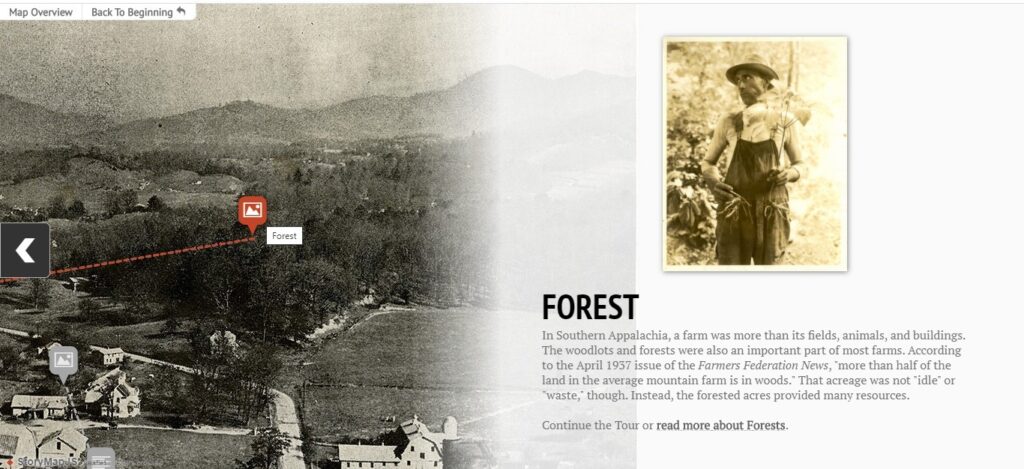

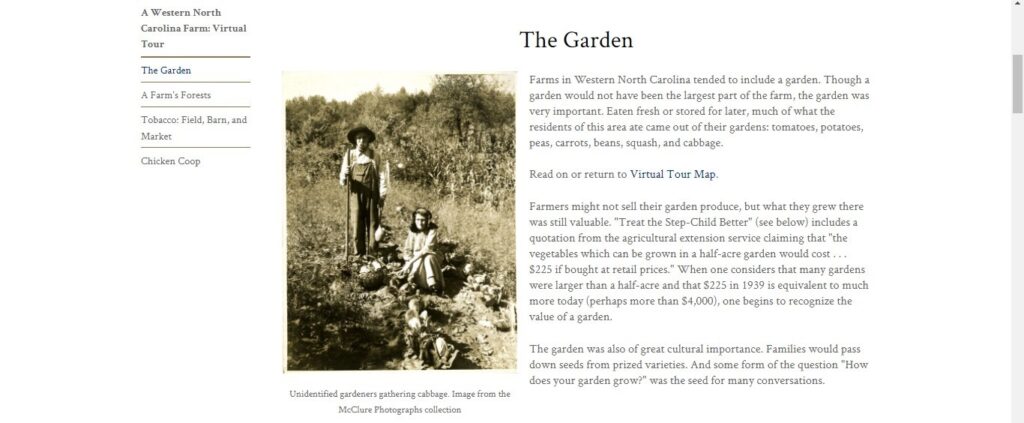

The team selected these “tour stops” deliberately. Tobacco was a vital driver of western North Carolina’s agricultural economy during the first half of the twentieth century, and the Federation devoted a great deal of content in the News to the cultivation, curing, sorting, and sale of tobacco. However, farmers in the region (and throughout Southern Appalachia) also relied on their gardens and the forest for much of their own sustenance. Well aware of the needs and cultural practices of their readers, the News encouraged gardening as a cost-saving measure and emphasized forest management as a source of supplemental income. Finally, the Federation began a “100 Hens on Every Farm” campaign early in its history—underscoring the possibility for almost any farm in western North Carolina to generate some profit from poultry.

Each tour stop links to a more detailed page on MHU’s Southern Appalachian Archives website. On these pages the research team was able to include far more of the content they uncovered through their research.

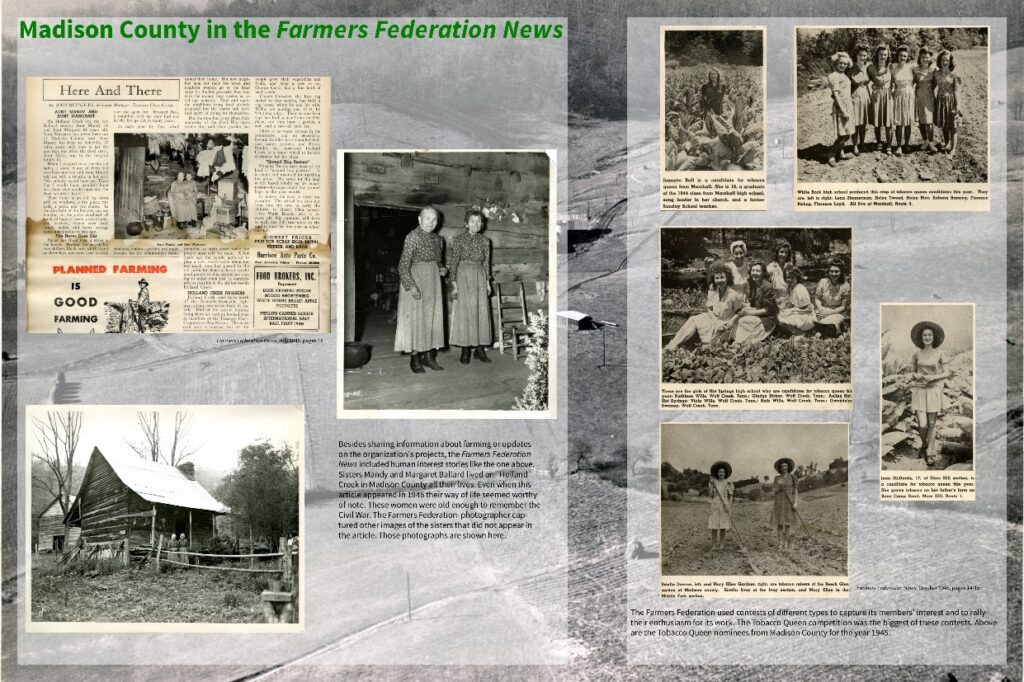

2) Exhibit Panels

Madison County, North Carolina is a place without universal internet access. Part of the CIC’s goal in promoting the “Humanities Research for the Public Good” program was to share widely the information gleaned from the archival collection under consideration. In writing our grant application, the team saw a role for a physical exhibit that complemented the work being done in the digital realm. We therefore adapted the content from the Virtual Farm Tour to fit onto printed panels. Several additional panels share Madison County-specific content from the Farmers Federation News and the McClure Photograph collection. We purchased easels for the ten panels in the exhibit, and both the Ramsey Center and the Appalachian Barn Alliance will at some point host the exhibit and loan it out to area institutions like libraries and schools

3) Presentation

In November of 2020, the researchers presented their findings to an audience gathered on Zoom. Their presentation summarized the project and discussed how the Federation influenced the diversity of food plants in western North Carolina. As they explained, their hypothesis—that the Federation encouraged farmers to adopt high-yielding varieties, and that the Federation’s influence decreased the diversity of field and garden crops in the region—was only partially correct.

On the one hand, functioning as an effective cooperative required that those selling through the Federation grow the same varieties. Thus, the Federation encouraged farmers to adopt particular plant and livestock varieties in order to produce a uniform product for market. For example, at various points during its existence, the Federation dictated that farmers grow “Porto Rico” sweet potatoes, “Irish Cobbler” potatoes, “Early Jersey Wakefield” cabbage, and “Marglobe” tomatoes. While this push toward standardization is understandable, it nevertheless required some sacrifices. In the case of the Marglobe tomato, the Federation celebrated the following “outstanding qualities” of the variety: it could “withstand long periods of wet and unfavorable weather,” was “resistant to Nail Head Rust and Fusarium Wilt,” and was a “good shipper” and a “good canner.” Noticeably absent from this list is any claim about the flavor or taste of the marglobe, suggesting that the Federation viewed this tomato more as a commodity than as food.

The Federation’s adoption and promulgation of the marglobe tomato provides a representative example of the organization’s focus on the economic welfare of the farmer. Gardeners and consumers are unlikely to relish a tomato bred for only vigor and shelf stability, but western North Carolina farmers needed a variety that would bear even in bad years and that produced fruit that could reach distant markets. Thus, the Federation favored the marglobe because they thought it the best candidate to help with their larger effort to improve the livelihood of the region’s farmers.

Part and parcel of the Federation’s economic focus was an effort to modernize farming and the farmer. As the research team read through years of issues of the News, they consistently encountered articles and advertisements that coached and cajoled the farmer to leave behind old ways and adopt the new—whether the new took the form of improved livestock and plant varieties, land management practices like contour plowing, or technology and machinery. An advertisement in the September 1922 issue of the News explained that adopting a Fordson tractor was “not a question of being able to afford a Fordson; it is a question of being able to continue farming on the old, too-costly basis” (p. 8). Similarly, an ad for fertilizer in the January 1937 issue of the News began “DO YOU FARM OR LIVE AS YOUR GRANDPA DID?” (p. 2).

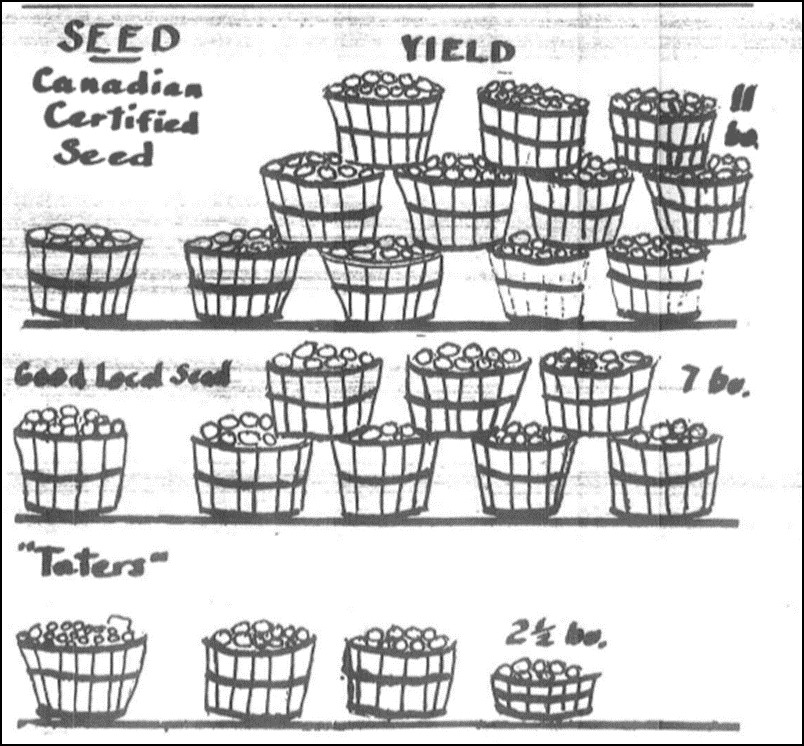

Advertisements like these illustrate an ideology of “progress” that devalued the past. The News and the advertisements it ran tended to challenge and undermine local traditions, including the seed-saving traditions preserved by farmers in the region. In the calculus promoted by the Federation, yield, quantity, and production outweighed other considerations: flavor in the case of the marglobe tomato and, as the sketch below suggests, a local, community-oriented food system.

Sketch that appeared in the March 1933 issue of the Farmers Federation News.

Sketch that appeared in the March 1933 issue of the Farmers Federation News.

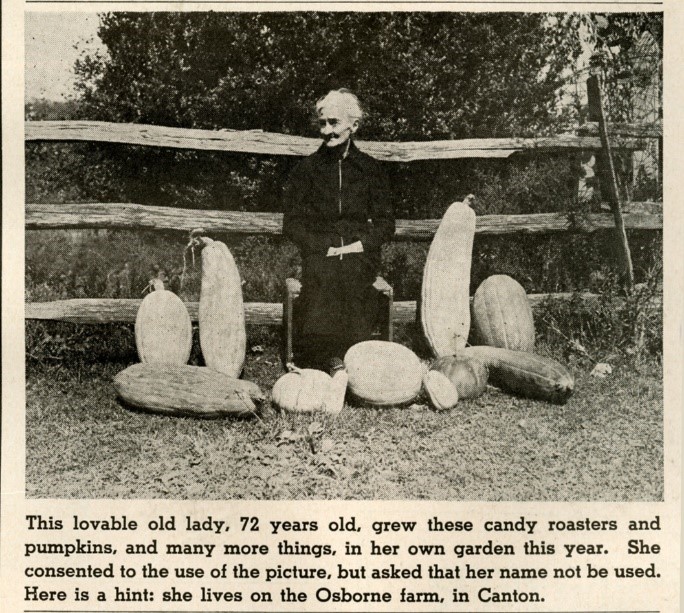

On the other hand, the Federation recognized that the lives of its members involved more than producing food commodities for distant markets and that many of them were not ready to embrace modernity. In fact, the Federation understood that gardeners and seed savers in western North Carolina had, over time, developed heirloom varieties unique to the region and its micro-climates. The News celebrated and supported these traditions. For example, the December 1944 edition of the News included a photograph of an elderly woman and the impressive collection of candy roaster squash she had grown.

Human interest stories like the one above make clear that the Federation’s mission broadened beyond a singular focus on profit. In fact, those familiar with the Federation and McClure might remember The Lord’s Acre program—a regional philanthropic effort that continues to make an impact in a somewhat different form in western North Carolina today.

The Farmers Federation’s evolving stance on hybrid corn illustrates the way the organization prioritized the economic welfare of the western North Carolina farmer and, consequently, undermined older (and sometimes ancient) food production practices. Throughout the 1920s, the News stressed the importance of carefully selecting and saving seed corn from one year’s crop to plant the following year. From example, an article from the November, 1920 issue of the News directed farmers to “select [your] own seeds and spend enough time to have something good” (p. 2). The June 1929 issue honored farmer James Monroe Jarvis for developing, over a period of thirty-five years, his Jarvis Golden Yellow prolific corn (see p. 9). The frequent seed-saving reminders and advice, as well as the awarding of honors to farmers who had developed open-pollinated varieties, indicates that hybrid corn was not available in western North Carolina during the 1920s and much of the 1930s.

The first mention of hybrid corn found by the researchers was in an advertisement for Wood’s Hybrid Early Yellow Dent corn that appeared in the March 1938 issue of the News (see p. 21). The ad described the variety as capable of increasing yields 15 to 30%. Interestingly, the News also published articles advising farmers against adopting hybrid varieties. In “Plan a Farm Program for 1939,” a writer for the News labeled planting hybrid corns “a rather hazardous undertaking” due to the fact that “many of the hybrids are not adapted to our climate and soil” (January 1937, p. 3). By the middle of the next decade, the News had altered its stance: “now hybrids are being made that are suitable for Western North Carolina” (December 1945, p. 14). However, the News was not offering a whole-hearted endorsement of hybrid corns. The same article went on to warn farmers that “you cannot select your seed from hybrids for planting the following year,” and an article from three months earlier had reiterated long-standing advice about selecting seed carefully from open-pollinated varieties: “leave some good two-eared stalks to mature for seed next year. Regardless of your variety, unless it is hybrid, you can increase your yield each year by field selections” (September 1937, p. 7).

The Federation’s treatment of the choice between open-pollinated corn and hybrid corn establishes the organization’s focus on western North Carolina farmers. Until hybrids were proven successful in the region, the Federation encouraged farmers to continue selecting seed from open-pollinated corn varieties. And even after proven hybrids were available, the Federation warned farmers that growing hybrid corn would require that they sacrifice some of their autonomy since the seed from hybrid corn will revert to the characteristics of one of the parent stocks.

Conclusion: Archives and Heirlooms

The “Influence and Legacy” project concluded that the Farmers Federation did much to multiply opportunities for farmers in western North Carolina. Their cooperative model enabled farmers to purchase supplies at bulk discounts and to sell their produce to distant markets. The News provided information about land and forest management practices from as far away as Germany. The Federation also built infrastructure that created new opportunities for farmers: a cannery in Henderson County as well as sweet potato curing barns, hatcheries, warehouses, and railroad sidings throughout the region.

However, the Federation also marched farmers down the path that has now, in the twenty-first century, deposited them in an agribusiness marketplace that is not kind to mountain farmers. Hybrid corn has given way to GMO; embracing economies of scale has birthed concentrated area feeding operations; and without the Federal price support program, tobacco has all but disappeared from small farms in western North Carolina.

Today, the issues of The Farmers Federation News exist as yellowing pages that can transport a reader back to farming’s history in this region. The farms described in those pages practiced a diverse and mixed agriculture; rather than specializing in one product, the same farmer might sell eggs, tobacco, cattle, potatoes, apples, and timber during different seasons of the same year. The farms were also peppered with the buildings and other features that enabled farmers to meet many of their own needs: smokehouse, coop, bee-yard, orchard, springhouse and garden. These same kinds of buildings and features are currently re-appearing in backyard homesteads. Perhaps the documents housed in the Southern Appalachian Archives at MHU can contribute to the rethinking and reshaping of regional food systems that is happening now. Perhaps those articles and blueprints (some of which are included in the virtual tour) will be recognized as valuable knowledge from the past—as heirlooms. The researchers involved in “The Influence and Legacy” project certainly hope that is the case.