The Appalachian Bibliography at West Virginia University: A History

By Stewart Plein

This article appeared in the Volume 1, Issue 1 Spring/Summer 2019 issue of the Appalachian Curator. Click here to view a PDF of the full issue.

“The current revival of interest in the Southern Appalachians differs from previous ones in at least two important respects. It is centered largely in the universities, and those conducting the studies are trained in research. Equally important, there is a general recognition that both sustained and well-coordinated efforts are required.”[i]

The history of the Appalachian Bibliography is both expansive and profound, and it rests on the shoulders of librarians who worked decade after decade to identify and compile the richness of the region in research, geography, foodways and folklore, travel and natural history, biography, memoir, and genealogy, as well as many other topics. As a research tool it has moved and grown through the changing methods and subjects of study and survived the many revolutions in modern library practices.

It all began with Robert F. Munn, an unsung figure in the study of Appalachia. His book, The Southern Appalachians: A Bibliography and Guide to Studies, published in 1961, along with the Appalachian Outlook[ii], a quarterly index of Appalachian topics, became the foundation for today’s online version of the Appalachian Bibliography. Both Munn’s work on the Southern Appalachians, and the periodical Appalachian Outlook, were published by the West Virginia University Library.

A pioneer librarian and Appalachian scholar, Munn sought to understand the region and make it understandable to others through a series of bibliographies. His first, Index to West Virginiana, was published in 1960. The Southern Appalachians: A Bibliography and Guide to Studies followed the next year. The 1970’s saw Munn continue to produce important bibliographies with the publication of his work, Strip Mining: An Annotated Bibliography, and finally, The Coal Industry in America: A Bibliography and Guide to Studies. Each bibliography was based on a special book collection designed to illuminate these topics developed by Munn for the WVU Library. Here was a man who saw what was happening around him and worked to collect, compile, and create the documentation in order to make it available to readers and researchers through his collections and publications.

In his introduction to The Southern Appalachians, Munn drew on his own article, “The Latest Rediscovery of Appalachia,” published in the journal, Mountain Life and Work,[iii] and from there he contributed to the interest and study of Appalachia. In both of these pieces Munn discusses what he calls the “rediscovery of Appalachia,” as an event that resuscitates the region and its people into the American consciousness, recurring approximately every 30 years.

Munn gives a glimpse of these cyclic resurgences, beginning with the rise of local color literature, in the magazines and books that appeared at the turn of the twentieth century. A literature of both fiction, non-fiction, and sometimes a combination of the two[iv] that developed, enforced and cemented the stereotypes of Appalachia that are still with us today. In this, the first in a line of re-evaluations, Munn calls out Charles Gooddell Frost’s[v] description of Appalachia as the “mountainous backyards of nine states,” and the brief but intense popularity of local color literature by the likes of John Fox, Jr. and Mary Noailles Murphree, writing as Charles Egbert Craddock, among others “who popularized stereotypes from the rugged mountaineer and mountain maid, to the barefoot hillbilly, and the feuding Hatfields and McCoys.” [vi]

The next wave of interest in Munn’s thirty year cycles hails from the Depression era, with the rise of a variety of government sponsored work projects such as the CCC, and the WPA. These work projects, an outgrowth of the preceding Progressive Era, were efforts to support, advertise, popularize, and enhance travel through the region and its newly created parks; Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and the Blue Ridge Parkway, among others. Though the work to develop these parks displaced residents whose families had lived on their land for decades or even centuries, these parks remain today as a reminder of the beauty and natural diversity of the region.

Munn found himself living in what he termed the third thirty year resurgence. This was the 1960s’ society as a state of flux that saw the rise of the civil rights era, space exploration, the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, Jr., and a focus on Appalachian poverty as revealed by Harry Caudill’s Night Comes to the Cumberlands and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, that aimed to erase poverty by making it front and center on the television sets of American citizens across the country. Each of these periods of renewed interest in Appalachia and its people are represented in the Appalachian Bibliography.

The West Virginia University Appalachian Bibliography is not alone in its attempts to collect the publications, recorded music, recipes and natural history of the region and its people. Before and after this effort, other bibliographies took on the long process of searching for information, compiling data, and aggregating the results in bibliographies, each one limited in time and scope, but each one continuing the important task of recognizing and publishing the various works, as they interpret our Appalachia. Notable among these are Lorise C. Boger’s The Southern Mountaineer in Literature: An Annotated Bibliography (1964), Charlotte Ross’s Bibliography of Southern Appalachia (1976), Marie Tedesco’s Selected Bibliography (2007), and John R. Burch, Jr.’s The Bibliography of Appalachia (2009).

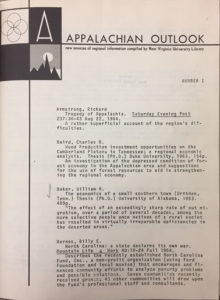

The first iteration of the WVU Library’s bibliography was a collaborative effort. The published indexes from the Appalachian Outlook quarterly and Munn’s The Southern Appalachians bibliography were combined to form the initial Appalachian Bibliography, which was published in three volumes. A cadre of reference librarians searched records and compiled information for the Appalachian Outlook, first published by the WVU Libraries in October 1964.

The Appalachian Outlook placed an emphasis on the social sciences, education and government documents. Before the days of computer databases, standard library indexes were checked as were individual journal entries. The Outlook finally came to a close in 2002, and all of its issues cumulated in the Appalachian Bibliography, first in 1972, and updated in 1977 and 1980.

The life of the bibliography extended over a number of modern library practices. When computerization began to invade the traditional tasks of thelibrary, it too left its mark on the Appalachian Bibliography. Carroll Wilkinson, University Librarian, was hired in 1979 for her first position at WVU as reference librarian and Appalachian bibliographer. At that time, the head of reference, Cliff Hamrick, created a paper form with a number of bibliographic fields along with space for annotations. Carroll Wilkinson’s responsibility was to fill out the forms, checking the indexes and drafting the annotations. Ms. Wilkinson explained that collecting citations, reading the indexes and assigning subject headings were all part of the job. [vii] Tools included extensive, homegrown authority files of subject headings and cross references.[viii]

The handwritten citations were typed on a keypunch machine that generated Hollerith cards,[ix]an early computer punch card, which were then fed into IBM reader machines. From approximately 1964 to 1984 the information for the Appalachian Outlook was typed by assistant Marianne Courtney to create the cards. To accomplish this, she hand carried the prepared slips of citations to Stewart Hall, the university administration building, and hand punched the information into the keypunch machine located in the basement. It was an unforgiving task since any mistaken keystroke required rejecting that card and beginning again with a fresh one. Hollerith cards as well as a large green printout with holes punched on the sides could be produced from the keypunch machine. The printouts were bound[x] and placed at the reference desk for public use.

The first program that processed the information was called WYLBUR, a text editor developed at Stanford University. WYLBUR was followed by ProCite[xi], a word processing software created in the 1980s. Finally the shift was made to Microsoft Word before the Appalachian Bibliography found its final home as an online accessible file.

Ms. Jay Morgan-Bungard was the next person to fill the position of Appalachian bibliographer. She held this role from 1980 to approximately

1985. Librarian Jo Brown, the helmsman of the modern Appalachian Bibliography, joined the WVU Library in 1981. He began contributing to the bibliography and became editor in 1985. He described the process this way, “Our hybridized master list of subject headings, sub-headings, and cross references, written on 3×5 cards, (was) filed in several shoe boxes.” [xii] Brown goes on to say that “Writing a descriptive but concise annotation was a valuable, honed skill, but so was the selection of up to five correct subject headings.”[xiii] It was this information, “slip by slip, line by line,”[xiv] that was keypunched onto the Hollerith cards for the Appalachian Outlook, “eventually culminating in a 1980 edition of approximately 8,000 entries. This information, arranged under 175 topics and indexed by hundreds of subject headings, along with Munn’s Southern Appalachian Bibliography, forms the foundation of the Appalachian Bibliography as we know it today.

In the early days, Munn chose not to index fiction[xv] in his Southern Appalachians bibliography. When Jo Brown took on the bibliography as a solo project he began including fiction and dissertations. These two areas provided an important addition. Fiction traced a burgeoning field while dissertations revealed the work of emerging researchers, often on topics that are ignored or overlooked by mainstream scholars.

The Appalachian Bibliography found a new life and wider exposure for nineteen years (1994-2013) within the pages of the Journal of Appalachian Studies. As the bibliography grew in length, and took more and more of the space dedicated to articles and reviews, the journal opted to end its publication of its “Annual Bibliography” and the printed edition of each year’s compilation came to an end. The Appalachian Studies Bibliography [xvi] lives now as a free online resource available in two formats: PDF and HTML. This version of the bibliography is split into two timelines, 1994 – 2012, and the recently added, 2013-2016. Each of these online formats contains a wealth of topics arranged under twenty five subject headings.

Both of these outstanding librarians, Robert F. Munn and Jo B. Brown, have been recognized for their contributions to the scholarship on Appalachia and their dedication to the creation and sustained maintenance of the Appalachian Bibliography. At WVU the Robert F. Munn Library Scholars Award for the Humanities and Social Sciences[xvii] is awarded each year to a graduating Honors student for outstanding research contributions in the humanities or social sciences that have culminated in the production of an exceptional thesis or capstone research paper. In addition, Dr. Munn was posthumously awarded WVU’s highest award for service, the Order of Vandalia,[xviii] the equivalent of a honorary degree.

In 2017, librarian Jo Brown was awarded the Cratis D. Williams/James S. Brown Service Award[xix] in recognition of his long service to Appalachian Studies and the Appalachian Bibliography.

At the present time, the future of the Appalachian Bibliography is undecided. Jo Brown’s recent update to June 2016 is the last installment to the bibliography. Options are available to continue this work but it will require a dedicated team to pick up the thread.

As Dr. Munn anticipated, it appears that we have entered into a new resurgence of interest in Appalachia, given the current conversations regarding depictions of Appalachians and the region through books such as J.D. Vance’s memoir, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis.[xx] The reviews, commentary, and press that followed publication have reignited the old stereotypical stories and unleashed a passionate conversation on the subject that inspired published responses such as Elizabeth Catte’s What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia,[xxi] and the newly released Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy,[xxii] edited by Anthony Harkins and Meredith McCarroll. In the midst of this discussion, the Appalachian Bibliography offers a wealth of resources to place this renewed interest in broader context and anticipate future interest in the region and its people.

In conclusion, as Dr. Munn states in the introduction to The Southern Appalachians: A Bibliography and Guide to Studies, “Comprehensiveness was the goal, and no effort was made at evaluation.”[xxiii]

This has to be. To allow the geographer, the passionate enthusiast, the scholar, the musician, the quilter, the digger of ginseng, the musician, and the miner to speak within the confines of the Appalachian Bibliography, is to allow the full portrait of the thinking on Appalachia, good, bad or otherwise, to be known, to be examined, recognized and understood, no matter the vantage point, as a way to understand our own region and its people. Taken all together, as the Appalachian Bibliography does so successfully, it provides a full range of resources and invites everyone to read, and to study, the full and unadulterated history of our region.

Stewart Plein is Curator of Rare Books & Printed Resources at the West Virginia and Regional History Center at West Virginia University Libraries. Stewart.Plein@mail.wvu.edu

_________________________________

[i] Munn, Rober F. Introduction, The Southern Appalachians: A Bibliography and Guide to Studies. Morgantown: West Virginia University Library, 1961, p.2.

[ii] Appalachian Outlook: New Sources of Regional Information Compiled by West Virginia University Library, was published by the West Virginia University Library, 1964 – 2002.

[iii] Munn, Robert F. “The Latest Rediscovery of Appalachia,” Mountain Life and Work, XLI (Fall 1965)

[iv] The work of James Lane Allen and Ellen Churchill Semple come to mind. Both used fiction to inform their ideas and scholarship on Appalachia and refer to it in their work.

[v] Frost, Charles Goodall. “Our Contemporary Ancestors in the Southern Mountains.” Atlantic Monthly, March, 1899. Vol. 83.

[vi] Jo Brown. Speech to Munn Scholar awardees, May 14, 2011. Unpublished. .

[vii] Conversation with Carroll Wilkinson

[viii] Brown’s note to author

[ix] Wikipedia punch cards: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punched_card

[x] The lower cover had nylon pins that held the printout in place, another cover was placed on top and then secured.

[xi] Wikipedia. ProCite: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ProCite

[xii] Brown’s notes to author.

[xiii] Brown’s notes to author

[xiv] Brown’s notes to author

[xv] Jo Brown postulates the reason behind Munn’s exclusion of fiction at the time was due to the publication of Lorise Boger’s, The Southern Mountaineer in Literature bibliography, published by the WVU Library in 1964. Brown speculates that Munn may have thought that Boger would continue to compile and publish the literature bibliography.

[xvi] Appalachian Bibliography: https://wvrhc.lib.wvu.edu/collections/appalachian/bibliography/

[xvii]Robert F. Munn Library Scholars Award for the Humanities and Social Sciences https://www.honors.wvu.edu/academics/resources/munn-award

[xviii] Order of Vandalia: https://vandalia.wvu.edu/

[xix] Cratis D. Williams/James S. Brown Service Award: http://appalachianstudies.org/awards/pastrecipients/

[xx] Vance, J.D. Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. New York, NY: Harper, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers, 2016.

[xxi] Catte, Elizabeth. What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia. Cleveland, OH: Belt Publishing, February 6, 2018

[xxii] Harkins, Anthony, and Meredith McCarroll. Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy. West Virginia University Press; 1st edition, February 13, 2019

[xxiii] Munn, Robert. Introduction, The Southern Appalachians: A Bibliography and Guide to Studies. Morgantown: West Virginia University Library, 1961, p.2.

One Comment

Jimmy Smith

You attribute William Goodell Frost’s important, albeit misguided, essay to somebody named “Charles Goodall Frost.”