This article appeared in the Volume 3, Issue 1 Spring/Summer 2021 issue of the Appalachian Curator. Click here to view a PDF of the full issue.

By Christopher A. Miller,

Associate Director and Curator, LJAC; College Curator, Berea College

In recent years, the role of artifact collections in colleges and universities has been evolving. It is not that museums, galleries, or artifact collections are new on campuses. Nor is it new for students to occasionally encounter cultural artifacts. For a long time, a visit to a campus museum, a tour of some exhibits, and talk from a curator were a low-key break from the classroom. However, artifacts in the classroom are becoming more serious business. This change has been fueled by increasing scholarly respect for material culture sources, artifact pedagogies that move beyond connoisseurship, and the growing role of curation skills in the digital economy. Some college and university collections have been rebranded and their curators have been re-cast as curator-teachers. Berea College’s Appalachian Studies Artifacts Teaching Collection (ASATC), based in the Loyal Jones Appalachian Center, is an interesting case study of such evolution. Since 2000, this Appalachian artifact collection has been under redevelopment as teaching collection.

Berea College Three Appalachian Collections

Berea’s artifact teaching collection stands alongside its better-known Southern Appalachian Archives (SAA) and Weatherford-Hammond Mountain Collection (WHMC) both based in Hutchins Library Special Collections & Archives. The SAA consists primarily of 2D and digital archival materials. The WHMC consists of published materials. The ASATC consists of 3D artifacts and is based in the Appalachian Center. These three complementary Appalachian collections have grown up as siblings at Berea.

At Berea College, deliberate Appalachian artifact collecting began in the mid-1890s. Berea’s President William G. Frost (1854–1938) and faculty doing extension work began to collect “relics from the mountains” to serve as proof-texts for their conceptions of Appalachians as “our contemporary ancestors” and Appalachia as “the land of saddle bags.” Indeed, a handful of artifacts now held in the ASATC appear in photographic illustrations accompanying Frost’s writings about the region. Over time, Appalachian artifacts accumulated in the library’s Curio Collection or languished in various academic departments’ closets.

In 1962, the nearly 2,000 object Edna Lynn Simms Mountaineer Museum Collection was gifted to Berea College. Around 1915, E.L. Simms began visiting the Gatlinburg, Tennessee, area, hiking, building relationships with local families, and collecting artifacts of mountain life. In 1931, Simms opened the privately owned Mountaineer Museum near the entrance to the National Park. The museum was a Gatlinburg tourist attraction for 24 years. After Simms’ death in 1961, on advice from Allen Eaton, Simms’ children offered the museum collection to Berea College. After some deliberation, the college accepted.

The gift of the E.L. Simms collection prompted Berea College to gather its 3D Appalachian artifact holdings into a singular Appalachian Museum Collection. Berea hired a professional director/curator who, supported by undergraduate student workers, catalogued the collection according to museum standards, organized storage areas, and curated the initial set of exhibits. The Appalachian Museum opened to the public in 1970. The museum quickly grew into an active force collecting and interpreting Appalachian material culture. Its collections supported the watershed craft exhibition “Islands in the Land” (Pasadena Art Institute, 1972); the book, Kentucky’s Age of Wood (1976); the book, A Catalogue of Pre-Revival Appalachian Dulcimers (1983); the national travelling exhibition, “Ribs, Rods, and Splits: Appalachian Oak Basketry” (1988-1993); and “Gallery V (for Virtual)” first online museum experience in Kentucky (1994-1998) [ENDNOTE 1]. Initially, the collection focused on the mountain cabin experience. However, as Appalachian studies evolved, the Appalachian Museum followed, focusing on Appalachian folklife. It added nearly 2,000 regional folklife artifacts to the collection. The largest portion documented regional crafts and music.

During the 1990s, as has happened with many outward-facing university museums, the Appalachian Museum entered a tumultuous period. Around 1992, the college administration charged the museum to focus on collecting and interpreting 3D artifacts from Berea College’s history. The museum did so for several years, adding 500 Berea College history artifacts. Then, in 1997, Berea College’s strategic planning process recommended closure Appalachian Museum and the future of its artifact collections became uncertain. The Appalachian Museum closed to the public in May 1998.

Becoming an Artifacts Teaching Collection

In 1999, the Appalachian Museum’s artifact collection was transferred to Berea’s revitalized Appalachian Center accompanied by a mandate to redevelop the collections and associated programming for curricular service. In early 2000, I became the teaching curator of this rebranded Appalachian Studies Artifacts Teaching Collection and have since led he redevelopment. The transformation to a teaching collection has involved several coordinated

initiatives. First, course integration is our priority. We offer a in-class artifact encounters in a variety of modes. Each academic year we do about twenty in-course sessions involving about 200-300 undergraduate students (Berea enrolls 1,500) and 400-500 artifacts. In addition to Appalachian Studies and General Studies courses, classes regularly using the collections include ART113 Appalachian Weaving, ANR334 Appalachian Plants & People, ART325 Fibers 3, HLT 210 Health in Appalachia, and TAD213 Appalachian Crafts

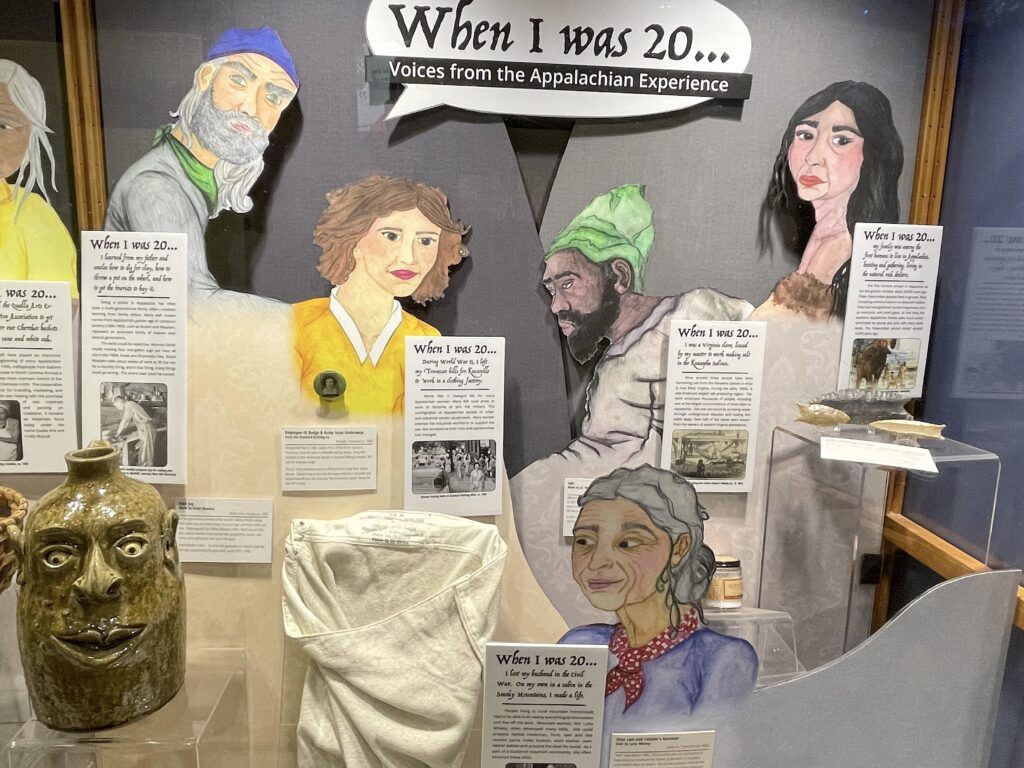

While the Appalachian Center is not a museum, exhibitions remain a part of its program and are open to the public on a more limited schedule. [ENDNOTE 2] However, in keeping with our mission, exhibitions are developed to support student learning about the region and course meetings in the gallery are common.

A teaching collection also requires different infrastructure. An oversize, flexible, well-lit classroom adjacent to artifact storage makes hosting in-class artifact encounters easy. The curator sets up in advance, students arrive at class time, and the curator cleans up after. This model is attractive to faculty and even feasible for short sessions. While artifact handling is typically involved, every session begins with a lesson about preservation and proper handling.

Every curricular use of each artifact is recorded, much like library circulation records. Even artifact storage has been optimized for a teaching collection using an open concept to make student and faculty “shopping” for artifacts practical and efficient.

While in-person artifact encounters receive priority, virtual exhibits and online catalogue access are also part of the program and increased in importance during the pandemic. However, designation as a teaching collection leads us to favor modes of digital access that contextualize the artifact. Our current offerings are on our website, in Hutchins Library’s LibGuides System, and in our new, still-emerging-from-its-cocoon LJAC DigitalAccess system (implemented in CollectiveAccess).

Our teaching focus also requires our collection development to be aimed towards making the ASATC into a better teaching collection. Its name begins with “Appalachian Studies” for a reason. The teaching themes and research interests of Appalachian Studies guide our acquisitions. For example, since 2000, we have built facets of the collection to support teaching about Appalachian identity and stereotypes, the social construction of places, Appalachian in the global economy, regional economic development, and global mountain living comparisons.

Finally, because of the Berea College’ required work-learning program, known as the Labor Program. The ASATC’s role as a learning laboratory for student curators not peripheral. Each academic year two undergraduate students interested in curation-related careers commit to working with the collection 10 hours per week for the entire year and each summer several students work half-to-full-time in internships. Many of these students have gone on to related graduate programs and careers as curators, librarians, or archivists.

After twenty years as a teaching collection, if is fair to make some assessments of the ASATC model. Use of the collection in public education significantly diminished [ENDNOTE 3]. However, the number of students encountering the collection increased four times and the amount of time each students spends thoughtfully engaged Appalachian material culture had increased ten-fold. The number and variety of artifacts utilized has also increased at least ten-fold. As a dedicated teaching curator, I consider the model for collections use in an academic environment to be a success.

Endnotes

ENDNOTE 1: Gallery V (for Virtual) was the first museum website in Kentucky to include virtual exhibits, not just marketing information. It remained available on the web until about 2016 at http://www.berea.edu/gallery/. It can still be seen at the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine at http://web.archive.org/web/20020615091535/http:/www.berea.edu/GalleryV/

ENDNOTE 2: The Covid-10 pandemic has eliminated public visits to exhibits since March 2020. However, typically the exhibits were free and open to the public from 8am-5pm on weekdays, except on college holidays.

ENDNOTE 3: The Appalachian Museum served about 15,000 public visitors per year during its years of operation.

One Comment

Tammy Clemons

Thanks for this excellent article about an excellent program that I have engaged with and learned from as a Berea student, professional staff, and occasional instructor over the past couple of decades.

I first toured the Appalachian Museum on a 4th-grade field trip, and I later wrote a research paper and produced a short documentary about its closing for Dr. Gordon McKinney’s “Appalachian Problems & Institutions” class as a Berea College student in the 1990s: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FpI6tTSCNAM. I interviewed Christopher Miller, Loyal Jones, Sydney Saylor Farr, Shannon Wilson, Theresa Burchett-Anderson, and visitors to the museum. I was disappointed with the closing at the time, but I have loved observing and participating in the multi-faceted evolution of the Appalachian Center and artifacts collection as part of Berea College’s service to the region and campus community.

Christopher Miller is an early innovator in material culture and digital humanities who has continued finding creative ways for people to learn/interact with them in-person and online. I have included his artifacts workshops in adjunct courses I’ve taught, and I frequently share his various digital resources. I consider Chris Miller an exemplar for integrating analog and digital artifact curation/exhibition, especially in the scholar-activist field of Appalachian studies, and I’m grateful for his expertise and collaboration as a colleague over the years.